Only days from an extended home leave during the Vietnam War, 26-year-old Marine 1st Lt. Robert Timberg was ordered on a routine mission that would upend his life, leaving him grievously disfigured and setting him on a sometimes arduous path toward journalism and literary acclaim.

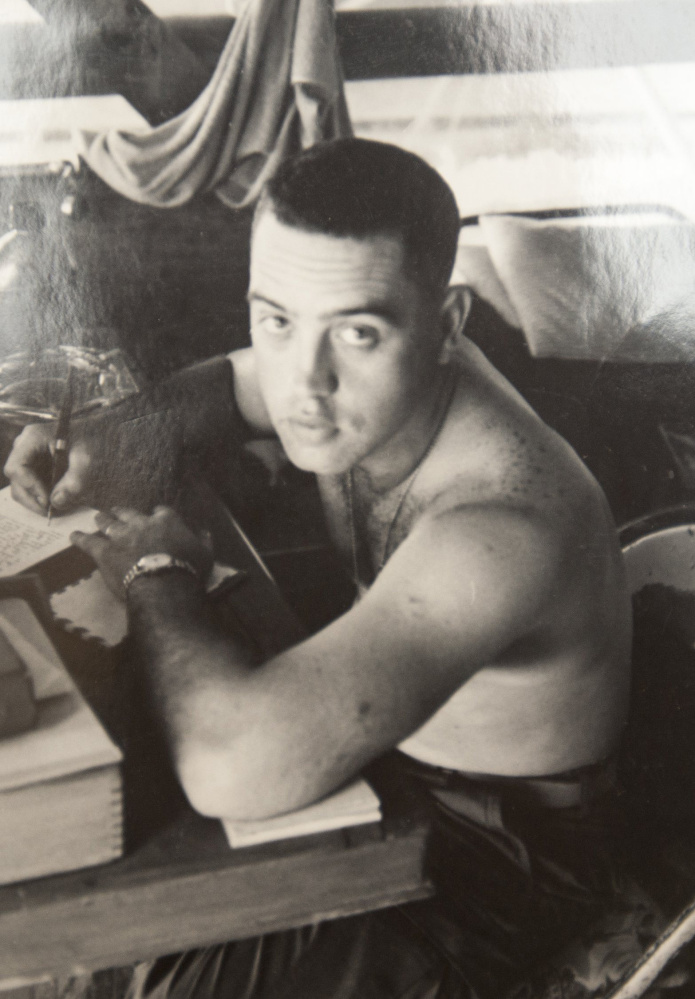

He set out from his base on Jan. 18, 1967, sitting atop an amphibious tractor and searching the treeline for enemy snipers as the vehicle rumbled through the rice paddies of South Vietnam near Da Nang. He wrote that the Amtrac carried hundreds of gallons of gasoline between the hull and deck plates – making it liable, if it rolled over a landmine, to trigger an inferno that would leave “anyone inside instantly fricasseed.”

When it struck the mine, he recounted in his 2014 memoir “Blue-Eyed Boy,” “I felt myself lifted as if in the eye of a hurricane, except in place of wind and rain I was being carried aloft by flames.” (The other men on board were not seriously injured.)

FIGHTING HIS WAY THROUGH

Timberg, who died Tuesday at age 76, endured more than 30 surgeries to repair the damage done by the third-degree burns that had nearly melted his face and scarred much of his body. During a surgery on his lower eyelids, a critical procedure that was performed without anesthesia because his body would not absorb the drug, he screamed so intensely and so long that the operation was a trauma also for the doctor.

Amid his recovery, he faced casually cruel reminders of his deformities. One Marine report spoke of his “highly repugnant” wounds. He overheard a nurse reduce his identity to his charred face, referring to him in shorthand as “The Burn.”

He foresaw a future defined by an endless cycle of surgeries and self-pity. He drank heavily, chain-smoked, fought suicidal impulses and scowled at his wife’s encouragement to find a new career after his discharge on medical disability. On a whim, she suggested journalism because she had admired the quality of his writing in his letters from Vietnam.

The prospect of regular interaction with strangers petrified him, but he grew convinced it was the only job that would never be dull. He began a long second career, becoming in time a Baltimore Sun political writer and editor in Washington, D.C. Besides his unsparing, well-received memoir, he wrote “The Nightingale’s Song” (1995), a piercing meditation on the Vietnam War and its long shadow.

The latter book traced the loosely interconnected destinies of five of his fellow Naval Academy graduates: Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., who had been brutalized as a prisoner of war; Marine Lt. Col. Oliver North, who became a top National Security Council aide; Navy Secretary and future Sen. Jim Webb, D-Va., who had written biting novels about Vietnam; and national security advisers John Poindexter and Robert “Bud” McFarlane.

Despite wildly different temperaments and personalities, all five had been deeply affected by the divisive war and public scorn for the military. Timberg saw President Ronald Reagan as the nightingale of the title, singing about renewed American military might and honor, and he described how his five subjects responded in various ways as they reached the echelons of power in the 1980s. North, Poindexter and McFarlane, for example, became central players in the Iran-contra scandal.

“In those early days of Iran-contra, I picked up a familiar and troubling aroma,” Timberg wrote. “Others saw greed, naked ambition, abuse of authority, a breathtaking disdain for Congress and the federal bureaucracy. I saw those things, too, but what I smelled was cordite, burning (buildings), the disinfectant odor of hospitals. … I remember thinking that perhaps Iran-contra was at least in part the bill for Vietnam finally coming due.”

‘CONSTANTLY TESTING MYSELF’

Robert Richard Timberg was born in Miami Beach, Florida, on June 16, 1940. His mother, Rosemarie Sinnott, was an Irish Catholic beauty who became a Ziegfeld girl. His father, Sammy Timberg, was Jewish and followed his siblings into vaudeville. He worked with the Marx Brothers and later composed background music for “Betty Boop” and other cartoons inked by Fleischer Studios.

By Timberg’s account, his father’s career did not fulfill its early promise, a failure that exacerbated both his sense of preordained failure but also his wife’s heavy drinking. The marriage imploded, and the children – Timberg and his two younger sisters – grew up with their mother in the New York borough of Queens.

Timberg threw himself into athletics and joined a successful Queens sandlot football club in large part because of its raw brutality. “I had inherited his fearfulness,” he wrote of his father in “Blue-Eyed Boy.” “I fought against it by constantly testing myself.”

It followed that after graduating from the Naval Academy in 1964, he chose service in the Marines “because it was tougher” than the Navy, and became an infantry officer “because I couldn’t imagine anything tougher than that.”

After his discharge, he studied journalism at Stanford University and began his new career as a cub reporter at the Annapolis Evening Capital. He enjoyed the intense pressure of deadlines, in part because it took his mind off his appearance – he said children often ran from him. (His visage became less shocking as he aged and the scars softened.)

In 1973, Timberg was recruited to the Baltimore Evening Sun, an afternoon paper where he covered the flamboyant and irascible Mayor William Donald Schaefer and eventually worked his way to the Washington bureau. He spent a year at Harvard University on a prestigious Nieman Fellowship in 1979-80 before landing an assignment covering Congress at the flagship sister paper, the Sun.

As a White House correspondent, he chronicled the Reagan-era operation to covertly sell weapons to Iran and divert some of the profits to right-wing Nicaraguan rebels known as the contras. That reportage, plus a long story he wrote for Esquire magazine in 1988 about Naval Academy classmates North and Webb, culminated in “The Nightingale’s Song.”

AMONG TOP VIETNAM WAR AUTHORS

Journalist and author David Halberstam wrote that Timberg’s volume “has an almost hypnotic authority all its own and belongs on the same shelf as those classics of the Vietnam War, Neil Sheehan’s ‘A Bright Shining Lie,’ Philip Caputo’s ‘A Rumor of War,’ and retired Lt. Gen. Harold Moore and Joseph Galloway’s ‘We Were Soldiers Once . . . and Young.’ ”

Timberg left the Sun in 2005 as deputy Washington bureau chief and for three years was editor in chief of Proceedings, the magazine of the U.S. Naval Institute. In addition to “The Nightingale’s Song,” he wrote a biography of McCain in 1999 and “State of Grace” (2004), focused on Timberg’s formative years playing for the neighborhood football team.

Timberg died at a hospital in Annapolis. He had congestive heart failure, said his son Craig, a journalist at The Washington Post.

In writing “Blue-Eyed Boy,” Timberg presented an often-embattled life. It was not his intent to foist another tome about courage and heroism on the world. He was wounded, found professional success and succumbed to weakness. Foremost, he endured when he thought he would not.

“I suspect there’s something essentially human about what I fought my way through,” Timberg wrote. “Somewhere buried in my memory, hidden beneath this terrible mask of scar tissue. I want to remember how I decided not to die. To not let my future die.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story