Water quality tests of more than two dozen private wells near the former Brunswick Naval Air Station showed no evidence of harmful contamination by a potentially toxic chemical in private water systems.

Navy officials are in the midst of testing water samples from homes in two neighborhoods of Brunswick, searching for a type of chemical that has contaminated groundwater in some areas of the former airbase. Those chemicals, known as perfluorinated compounds, or PFCs, are under increasing scrutiny as potential health threats after their widespread use in everything from industrial firefighting foam to non-stick cookware and food packaging.

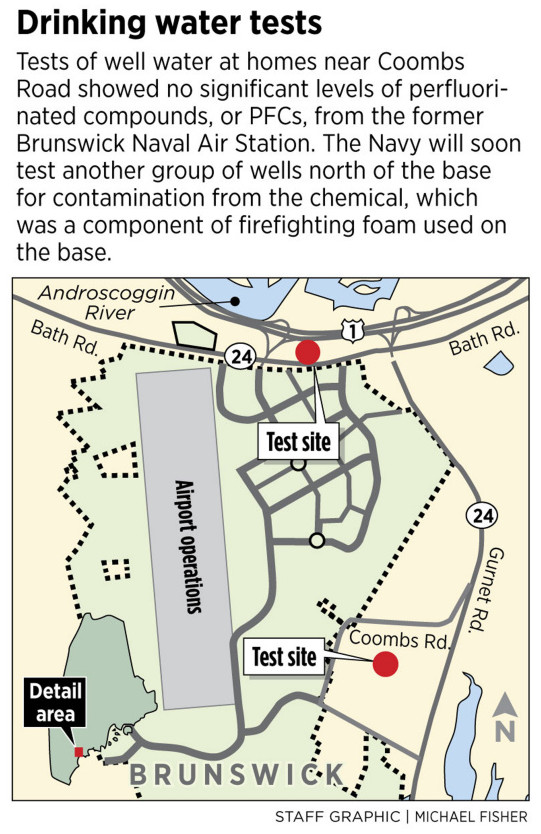

The Navy has completed tests of 27 private wells in a neighborhood nestled between the former Navy base’s southeastern edge and Route 24. PFCs were either undetectable or were at levels “well below the health advisory level” for all 27 samples, which were collected from willing homeowners, said Bill Franklin, spokesman for the Navy’s Base Realignment and Closure Program.

The Jordan Avenue well that helps supply Brunswick residents with drinking water also is tested regularly for PFCs and has a clean bill of health.

The Navy has sent letters notifying owners of the 27 wells about the results and is preparing to launch another round of testing, this time on in a neighborhood north of Bath Road.

“We are in the process of contacting the property owners to receive written permission to allow well testing. We anticipate the sampling to start late August/early September 2016,” Franklin said.

Although federal health officials say additional research is needed, animal studies have shown that some PFCs disrupt hormones, affect organs such as the liver and pancreas, reduce immune system function, and can cause developmental problems in offspring.

The chemicals were widely used for decades in products, including in Teflon cookware, stain-resistant fabrics and in the type of foam firefighting spray used at many military and industrial installations. As a result, traces of PFCs can be found in the blood of most humans and animals.

Concerns about the chemical have risen in recent years after they were detected in the drinking water near several military bases, including the former Pease Air Force Base in New Hampshire. In May 2014, Portsmouth shut down one of its public water system wells after tests revealed PFC levels that were up to 35 times higher than the 70 parts per trillion advisory level later set by the EPA.

At the former Brunswick Naval Air Station, testing revealed PFC contamination near a fire-training area, around a building where fire suppressant foam was deployed and in an area of underground contamination near Merriconeag Stream known as the Eastern Plume.

Suzanne Johnson, the citizen co-chair of the Restoration Advisory Board that helps oversee environmental cleanup at the former airbase, was pleased that the first round of testing showed no major contamination in the private wells.

“We know it hasn’t migrated, so now we need to figure out what to do on the base and how is that (contamination) managed?” Johnson said.

The Navy closed the Brunswick base in 2011 and transferred much of the land to either the town of Brunswick or the Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority, which is redeveloping the site now known as Brunswick Landing. The Navy has spent more than $100 million investigating and cleaning up pollution on the roughly 3,100-acre property.

Since the closure, more than 90 companies have set up shop at Brunswick Landing, which has attracted 950 jobs so far and could see employment top 1,600 this year. But the new construction on the base has raised some concerns about disturbing existing contamination, whether in groundwater or the soils.

Johnson and members of Brunswick Area Citizens for a Safe Environment have been pushing for years for a zoning change that would prohibit Brunswick Landing tenants from extracting groundwater anywhere on the former base property, which is connected to public water supplies.

Water extraction is already prohibited under deed restrictions attached to any land sales, but Johnson said deed restrictions could subsequently be modified. Johnson said citizen members of the Restoration Advisory Board – which also includes representatives of the Navy, the EPA, local towns and the Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority – also would like to see more safeguards put in place for managing any contamination risks during new construction.

But Steve Levesque, executive director of the Midcoast Regional Redevelopment Authority, does not see any wiggle room in the deed covenants already required on property transfers base-wide. Additionally, property owners are required to notify the Navy annually about any construction activity. Some deeds even require notification before work begins, Levesque said.

“There are restrictions and new property owners know those going in,” Levesque said.

The water testing and other contamination issues are likely to be discussed during the Restoration Advisory Board meeting scheduled for next month.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story