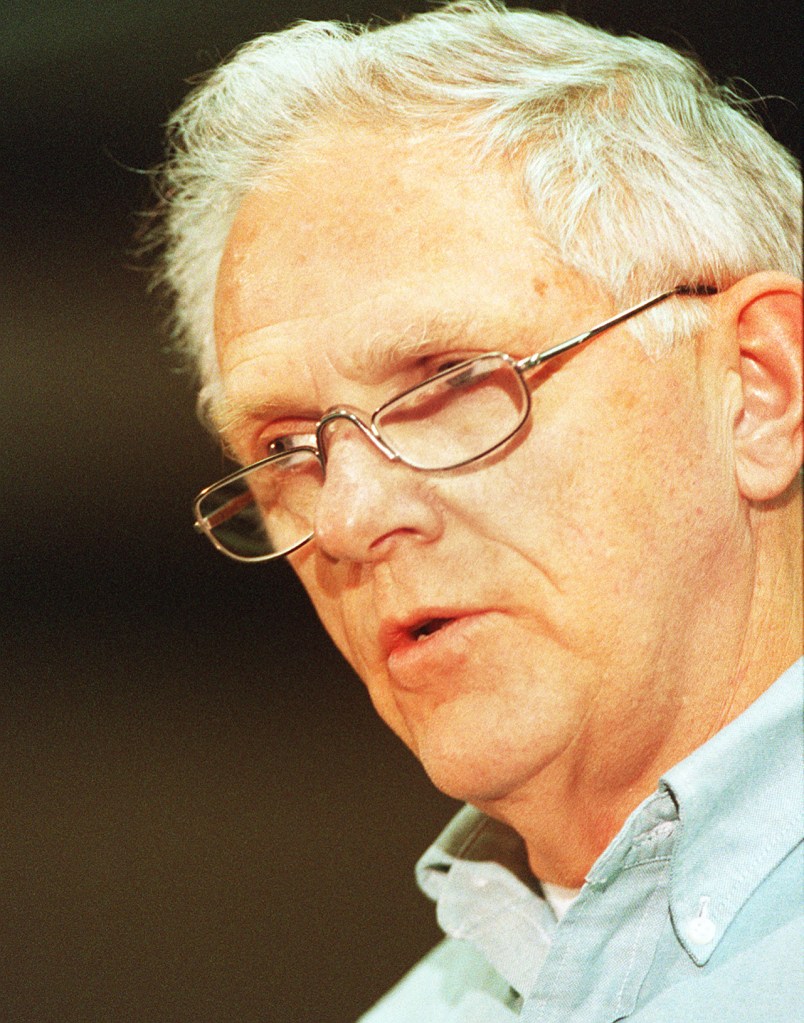

A retired mechanic from South Berwick who believes ethanol in gas may be to blame for Maine’s opioid crisis was a driving force behind Gov. Paul LePage’s decision to study the corn-derived gasoline additive.

The mechanic, Ralph Stevens, 77, said in an interview that he believes emissions from the additive have prompted the state’s ongoing drug crisis and may be responsible for a host of other health problems.

State Rep. Beth O’Connor, R-Berwick, seized on Stevens’ concerns, and has worked with him to study the issue for over six years. A letter she sent to LePage urging him to take action included written testimony that Stevens submitted to the Legislature outlining his concerns about ethanol.

O’Connor said it has taken her two terms in the Legislature to gain any traction on the issue, and she was giddy after the governor issued an executive order last week requiring all state vehicles to be fueled – whenever possible and when it is not cost-prohibitive – with gasoline that has an ethanol mix of 5 percent or less.

“It’s a good thing,” Stevens said of LePage’s order. “Maybe we will get to the bottom of it, from official people, because I can’t say that I’m official.”

But when it comes to additives in gasoline, Stevens has been right before. He was among those who successfully advocated in the late 1990s to ban the fuel additive MTBE from gas – making Maine one of the first states to do so – after it was discovered the additive could contaminate groundwater.

Ethanol is added to gas to improve its combustibility, and to reduce emissions that contribute to smog. It also lowers the emissions of benzene, a chemical produced from the combustion of gasoline that is a known carcinogen.

A federal Environmental Protection Agency fact sheet on ethanol, or acetaldehyde, notes it is a “group B2, probable human carcinogen.” But the fact sheet also notes that the risk of developing cancer from breathing air with acetaldehyde is relatively low based on a mathematical formula the EPA uses to determine cancer risks.

O’Connor believes the additive is causing health and even public safety problems.

“It has caused increased allergies, increased asthma. I believe it exacerbates the condition that a lot of our veterans have with PTSD. I believe that it causes depression, anger,” said O’Connor, who also asserted a link to higher crime rates in urban areas, where more ethanol is burned. To better get LePage’s attention, she had 85 members of the Legislature sign a letter she had drafted urging him to take action.

Those on the list come from both parties and span the political spectrum.

GAS WITHOUT ETHANOL MORE COSTLY

Jamie Py, president of the Maine Energy Marketers Association, an industry group for businesses that sell fuels, including gasoline in Maine, doesn’t believe there are substantial health issues with ethanol emissions. He also said there’s no great support for ethanol among those who are required by law to sell it under state and federal air quality laws.

Py said there are currently processes available to produce gasoline without ethanol that meet all of the other emission standards, but it results in a more costly fuel. Py also said he believes if there were serious health concerns connected to the use of ethanol it’s likely they would have been discovered by now.

Py said he hadn’t heard the theory that burning ethanol might be a cause for the opioid addiction crisis in Maine.

“I would have to look into what his background is on that,” Py said. “You could pass a bill in the Legislature that says we are not going to sell ethanol gas in the state of Maine, but the problem is, what would it cost?”

There are 13 places in Maine that sell ethanol-free gasoline, most of them airports and marinas, according to the website pure-gas.org. A check of the cost of ethanol-free gas Thursday showed it was selling for $3.63 a gallon, compared with regular gas, which contains 10 percent ethanol and is selling for an average of $2.31 a gallon.

Py said Mainers buy about 700 million gallons of gas a year, meaning they would spend about $924 million more for gas at current prices.

LePage’s order requires the state’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention and its Department of Environmental Protection to collect the available studies on the health and environmental impacts of burning gasoline that’s mixed with ethanol, review that information and report back on what should be done, if anything.

John Martins, a spokesman for the Maine CDC, said several studies on ethanol – including one from Health Canada in 2010, a few from California and from the Northeast States for Coordinated Air Use Management from the early 2000s – were being collected and reviewed. Likewise, David Madore, a spokesman for the Maine DEP, said the department was in the planning process with the Maine CDC about how it will develop a report for LePage based on the executive order.

O’Connor said she had nearly reached her breaking point on the issue, and then the governor issued his executive order and also penned a handwritten note to her explaining that he couldn’t legally ban ethanol outright, but he could use his executive power in an attempt to limit the state’s consumption of it and to find out if there were any serious health concerns.

O’Connor said lobbyists that work for the oil and gas industry in Augusta had her so frustrated she told them to “go pound sand” as she pushed forward a bill this year that clarified ethanol-free gas could be sold in Maine.

“And I was getting ready to tell the governor to pound sand too,” said O’Connor, who works as a waitress when the Legislature is not in session.

“Mr. Stevens and I have been researching the corn ethanol issue for six years and have compiled thousands of pages of documentation that show clearly the government boondoggle this is,” O’Connor wrote in her message urging LePage’s executive order. “Most recently we have concentrated on the ill health effects from increased blends of corn ethanol in our gas and we believe this fuel source does far more harm than good and the faster it can be removed from the air we breathe the better.”

A YEAR AGO, LEPAGE VETOED ETHANOL BILL

And in an unusual move for LePage – who frequently laments the Legislature’s tendency to study problems instead of tackling them directly – he took her and Stevens’ concerns to heart and ordered the study.

“It’s important that with the increased use of ethanol-mixed gasoline that we understand the environmental and health risks associated with it,” LePage said in a prepared statement announcing the executive order. “This Executive Order will help identify data so we can make better informed decisions regarding the use of ethanol.”

Acetaldehyde is also the byproduct of drinking alcoholic beverages that is largely blamed for producing a hangover. The U.S. EPA also notes that “residential fireplaces and woodstoves are the two highest sources of emissions (of acetaldehyde), followed by various industrial emissions.”

LePage’s order comes just a little more than a year after he vetoed a bill by O’Connor that would have required the Maine DEP to study the health impacts of gasoline additives, including and especially ethanol.

LePage vetoed the bill, LD 824, in 2015, but he signed into law another bill in 2016 that essentially clarifies state law allowing Maine gas retailers to sell gas without the corn-based alcohol additive that many say is the bane of small engines – like those on lawnmowers, chainsaws, boats and snowmobiles.

In his 2015 veto message of O’Connor’s bill, LePage said the law that would have prohibited the sale of gasoline mixed with ethanol was in conflict with the U.S. Constitution, which, according to LePage, prohibits states from passing laws that impair the obligation of contracts.

O’Connor believes the veto was because ethanol and gas producers would both lose money. She said making ethanol-free gasoline widely available in Maine also would cut into the profits of retailers like big-box home-improvement and hardware stores, which sell ethanol-free gas, mixed with oil by the quart, that’s meant for two-stroke engines. She said quart pricing of so called “e-zero” gas is so steep that the per-gallon price exceeds $30.

“I think those are the contracts they were trying to protect, they wanted to continue to sell e-zero gas in one-quart cans that equates to almost $32 a gallon,” O’Connor said.

TAKING ON THE RESISTANCE

She said after meeting with LePage on the contract issue, she agreed to help sustain his veto in 2015. “But now, in retrospect, in knowing that petroleum is in bed with corn ethanol, I should have just said pound sand, told the governor to pound sand and told the petroleum industry and the ethanol industry to pound sand, I don’t care if your contracts are protected.”

Small engines and motors that are used in or around water are particularly susceptible to being damaged by ethanol-blended gasoline, because ethanol attracts water and can also cause certain engine parts, like gaskets, to deteriorate. Aircraft engine components are also susceptible to damage from ethanol.

And while LePage and the Legislature seem poised to move Maine farther away from the use of ethanol, President Obama also issued an executive order in 2015 mandating that 18.11 billion gallons of ethanol be blended into the nation’s fuel supply this year. That’s a 5 billion-gallon decrease from targets in a 2007 law signed by President George W. Bush requiring 22.3 billion gallons of ethanol in 2016.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story