Nearly a year before he allegedly killed a 52-year-old Alfred woman in New Port Richey, Florida, Timothy F. Johnson told another woman he wanted to rape and kill her before he attempted to act on the fantasy, the woman said.

On multiple occasions since the summer of 2015, Johnson told Sandra Cartwright, 47, a roommate of Johnson’s brother, about his urges to harm her, Cartwright said in a telephone interview. Then on Jan. 17 this year, Cartwright awoke to find Johnson, 25, in her home, brandishing a butcher knife, an attack she escaped only because another man staying with her that night fled to get help.

“He told me on one more occasion how he wanted to rape and mutilate me,” Cartwright said. “Tim and I had conversations about his thoughts. Tim knew he was sick. And I completely think he had no control over it.”

Johnson was charged with two counts of aggravated assault in that attack, but because Cartwright did not speak with prosecutors within 30 days of the crime, he was released on Feb. 19. Charges were filed a few days later, but Johnson was already back on the street. A few weeks later in March, Johnson met a woman from Maine who was in Florida for vacation: Judith Therianos.

Three people close to Johnson, including Cartwright and Johnson’s twin brother, Jarred, each gave chilling accounts of how Johnson’s alcoholism and violent tendencies toward women escalated in the last two years before he was charged in the brutal killing of Therianos, who authorities believe died on March 13 after a sexual encounter with Johnson.

Johnson’s family members and friends spoke of the toll his violence had taken on their lives before the killing, and the overwhelming sadness and guilt they feel that their efforts to get him help were apparently not enough.

Time and again, his family and friends watched as Johnson slipped through Florida’s judicial and mental health systems, most frustratingly in July 2015, even after a judge signed an order to have Johnson involuntarily committed and evaluated – the first step toward placing him in a long-term care facility.

But that order was never carried out. Johnson was mistakenly discharged from the psychiatric ward of Medical Center of Trinity Behavioral Health, instead of being transferred into the custody of sheriff’s deputies, per the judge’s order.

“For whatever reason something happened with the hospital staff and social services, and they gave him a pillow and blanket and released him,” said Suzanne Snyder, a retired Florida caseworker for the Department of Children and Families, and a close friend of the Johnson family who now lives with Jarred. “If that process had gone through the way that it should have, it would have given (Johnson’s) mom and brother the opportunity to go before the judge and file for guardianship, because he was out of control.”

SUSPECT’S PROBLEMS ESCALATED

A spokesman for the Medical Center of Trinity Behavioral Health, where Timothy Johnson was apparently released by mistake, declined to comment, citing federal patient confidentiality laws.

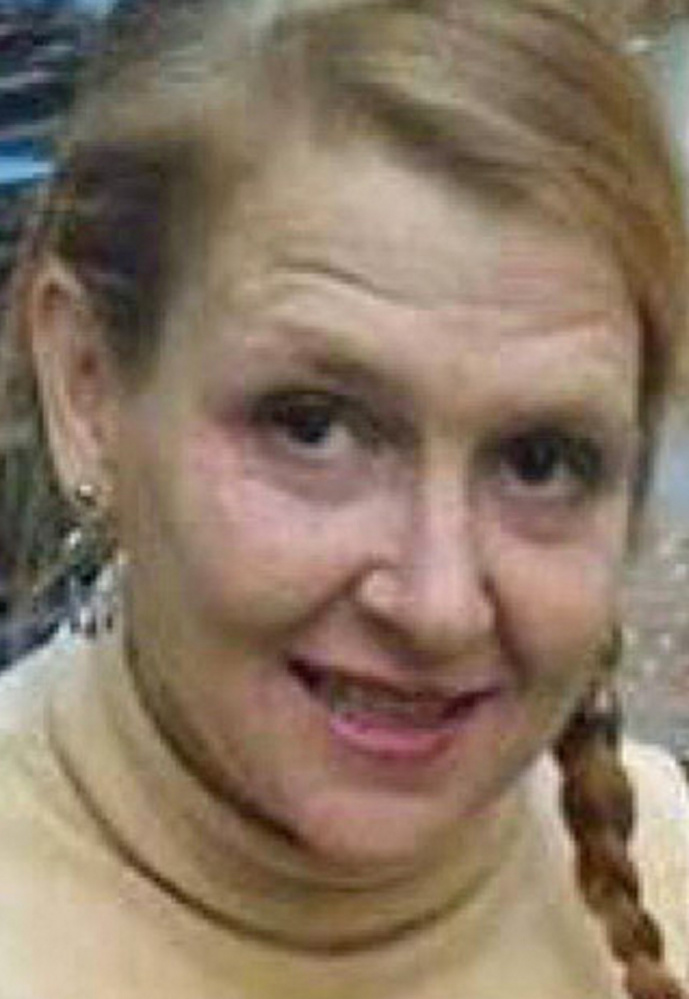

Therianos traveled to Florida in February to visit a friend and take a vacation. She told family she would return to Maine by Easter, but when she stopped returning phone messages, relatives reported her missing to Florida police. Therianos’ body was discovered on April 7 in a wooded area in New Port Richey near a commercial center.

Police say Therianos and Johnson met on March 13 at a liquor store before they went to a wooded area to drink and have sex. But when Therianos told Johnson to stop, he choked her until she lost consciousness, beat her to death and violated her body.

Police linked Johnson to the slaying through several witnesses who said Johnson confessed to killing Therianos.

A grand jury is expected to indict Johnson in the coming weeks. Prosecutors have not yet determined whether to seek the death penalty.

Although his family said they were shocked by the grisly slaying, they described how Johnson’s mental health and alcohol problems emerged and escalated over the last five years, and how, more recently, he had become violent toward women.

Timothy Johnson’s problems began early, when he was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as a child.

In May 2009, when Johnson was 18, he was shot in the head as he watched television in his living room by someone outside the house. The perpetrators were never caught, and Johnson spent weeks in a coma, said Snyder. But his family noticed a change when he awoke and returned to his daily life. He became more paranoid and anxious. His affect worsened still a couple of years later in 2011, after a fire that August destroyed the family’s home.

“After the fire, he would drink and get into these episodes,” Jarred Johnson said. “The slightest thing would set him off. He started breaking things in the house. He punched the taillights out of my vehicles.”

Jarred said their father, Stuart M. Johnson, was eventually convicted of setting the blaze and is serving a five-year sentence for arson in a Florida prison, but Jarred Johnson, Cartwright and Snyder said Timothy Johnson later admitted to setting the fire himself.

Chris LaBruzzo, assistant state attorney for Pasco County, could not immediately confirm whether the family brought Timothy Johnson’s admissions to their attention, or whether it resulted in any re-examination of Stuart Johnson’s conviction.

“We’re going to look into it,” LaBruzzo said.

Timothy Johnson often tried to fight his brother, and it was Jarred who would physically subdue him until police arrived.

Jarred Johnson said his brother’s first assault of a woman came in late 2014 or early 2015.

Johnson had moved to Michigan with a girlfriend, and fought with her after drinking one night. The girlfriend called police, and Johnson spent more than a month in a Michigan county jail. Their relationship ended and Johnson returned to his family in Florida.

“When he came back to Florida, that’s when it got real bad,” Jarred said. “He started to get violent. He’d get into these moods. He was unpredictable.”

‘WE HAD A VERY SICK YOUNG MAN’

The violence escalated. In a drunken rage, he held his mother, who suffered from serious health problems that were complicated by the stress of caring for her son, to the floor with a knife to her throat, Snyder said.

The twins’ mother, JoAnn Winters, died in January, and her death weighed heavily on both sons, according to both Cartwright and Snyder.

Often after police arrived, Timothy Johnson would be taken to a temporary facility through a provision of Florida law called the Baker Act, which allows authorities to hold and stabilize individuals for up to 72 hours if they are deemed a threat to themselves or others. Johnson had been “Baker Acted” more than 15 times between 2011 and March 2016, his brother and Snyder said.

But after each short stay in a mental health facility, Johnson was released.

According to statistics gathered by the University of Southern Florida, most people who undergo a Baker Act examination do so once. But a smaller number of individuals cycle repeatedly through the system, sometimes 10, 15 or 20 times over several years, said Annette Christy, associate professor in the department of mental health law and policy and the principal researcher at the Baker Act Reporting Center.

“We told everybody in the courts, the public defenders, that jail isn’t the best thing (for him),” Jarred Johnson said. “He really needs to be put in a psychiatric facility. The courts didn’t do anything. They just kept arresting him and putting him in jail, releasing him and putting him on probation.”

In June 2015, during one of Johnson’s violent episodes, he bit his brother, leading to charges of domestic battery and a restraining order that kept him from returning home.

About a month later in July, Jarred Johnson said he awoke one night about 3 a.m. to strange noises coming from his brother’s bedroom. Jarred Johnson found his brother holding down and choking a prostitute, an assault that ended only when Jarred tackled his sibling to the floor, giving the woman time to flee.

Frustrated with their inability to stop Johnson’s violence and drinking, the family petitioned a Pasco County circuit judge to involuntarily commit him through a law called the Marchman Act, which allows friends or family of individuals with a substance abuse problem to petition the court to commit them voluntarily or involuntarily to a substance abuse treatment program.

In the court filings, his mother and brother’s desperation was evident.

“Has coping problems with everyday stress, has PTSD. … Is on medication but doesn’t work!!!” they wrote, and suggested three treatment facilities where he could be taken.

On July 16, 2015, Pasco County Circuit Judge Philippe Matthey signed an order for deputies to pick up Timothy Johnson for a mandatory psychiatric and substance abuse evaluation – the family’s first step toward getting him into a long-term facility and off the streets.

Had the deputies taken him into custody and followed through on the evaluation, Snyder believes Therianos would be alive today.

“I don’t want to give anyone the impression that we condone his actions,” she said. “That’s not the situation. The situation is we had a very sick young man, and we did the very best we could.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story