HOLLIS — Duncan Hewitt tugs earnestly at the laces of his Mission skates, his rear end planted on the frozen edge of the pond.

“These are like rocks,” he says, flashing the blade as he leans backward and flexes his right leg to cinch the boot tighter still. He tolerates these stiff, modern skates but misses his leather CCM Tacks. They were old and broken down, and much more comfortable. He upgraded reluctantly a few years ago.

Hewitt lifts himself off the grass, grabs a wooden hockey stick and tosses a puck on the ice. In a few swift, shredding strides, he’s down the length of the pond, around the edge with a series of crossovers and back up the other side.

The sound of blades ripping the ice reverberates in the trees that surround this private pond, a sound punctuated only by the clap of a puck and the happy banter of two skaters on a sunny winter afternoon.

Hewitt, a sculptor, is showing 20 years of wood carvings at the Portland Museum of Art, all made while teaching art at the University of Southern Maine. He retired last year after 38 years. The Portland exhibition is his first major solo museum show.

If not for hockey, Hewitt might not be an artist. He grew up on Long Island, New York. He sailed in the summer and played hockey in the winter. He was good enough to make the Colby College team as a freshman, but he was undersized and didn’t last the season. “I got beaten up, so suddenly I was making sculpture,” he said. “As passionate as I was about hockey, I was never super-passionate about big-time college athletics. I just liked to go play hockey.”

He still does. Often as not, Hewitt keeps his stick and skates in his car, so he can hop on the ice whenever it’s convenient. The pond he’s chosen for this skate is about five minutes from his home in Hollis, on a friend’s property. It sits close to a small road and is ringed by trees. There’s a game here tonight, and Hewitt is debating playing. He still likes to play, but doesn’t like getting whacked now, at 66, any more than he did when he was a freshman at Colby. These pick-up games, he says, can get a little rough.

What he likes are these quiet mornings when no one else is around, when he can skate in looping circles and tight figure eights, with or without a puck and stick. He works up a sweat, his gray hair waving as he bends at the waist, swings his arms and grinds up the ice.

It’s little surprise that hockey found its way into Hewitt’s exhibition at the museum. He’s carved many skates over the years. A dozen ended up in this show. He used his old Tacks as a model for one set and the new Missions for another. He renders them lifelike, with detail, but leaves enough unsaid to allow the viewer to figure out what they mean or how to react. The boot is open, laces untied, and the skate is positioned in movement, as if engaged on a player’s foot, moving up the ice. The skate looks real. You expect it to smell.

“I want people to go right into the space and go right up to it,” he said. “They don’t believe it’s wood. They’re not sure what it is. It must be different enough that they know it’s not quite right, and close enough that it might be.”

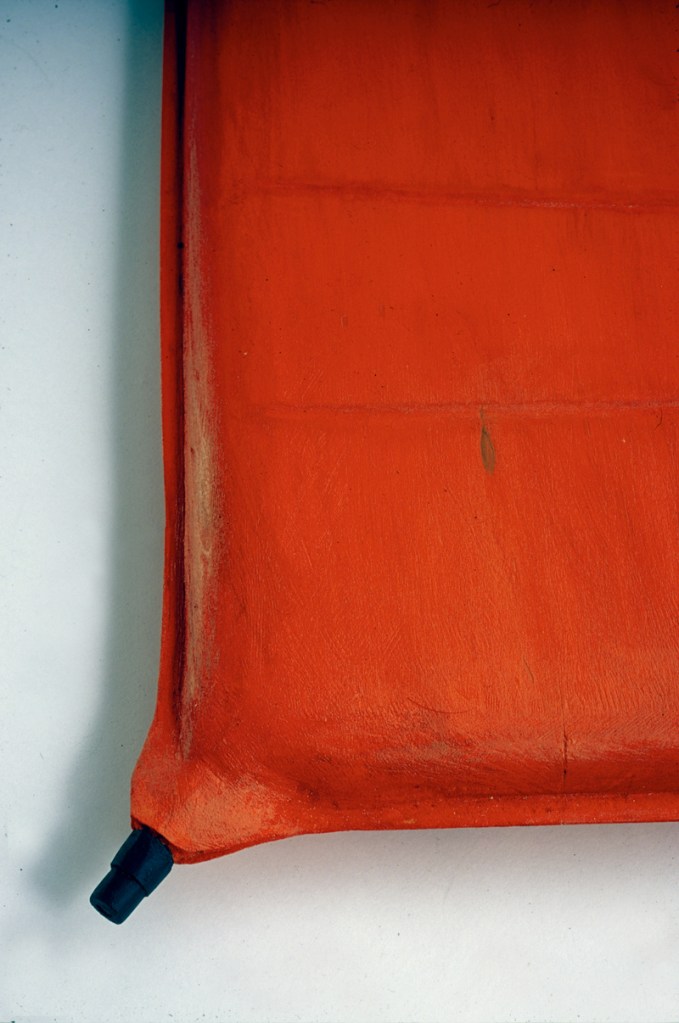

Hewitt carves what is familiar and what is part of his life – domestic objects in the literal sense: forks and spoons, and tin lids from cooking pots. And then there are inner tubes, ski masks and lollipops. He made a series of automobile windshields and rear-view mirrors.

He uses color sparingly, in a purposeful, painterly way.

His friend and former USM teaching colleague Richard Brown Lethem came away from “Turning Strange” with a new appreciation for prosaic objects. “I find the transformation by which Hewitt takes mundane objects, such as the auto windshield, and transforms it into an hallucinatory experience of reality truly amazing and visually exciting,” Brown said. “He’s got a unique take on the world around us.”

“Turning Strange” came about after Hewitt applied for entrance to the Portland Museum of Art Biennial. He didn’t get in, but instead of a rejection letter he received a note from Chief Curator Jessica May offering a solo show as part of the museum’s focus on contemporary art, through its Circa series. “Turning Strange” is on view through Sept. 4, on the third floor of the Payson Wing and in the McLellan House.

Hewitt’s work has been in two PMA Biennials, the Center for Maine Contemporary Art Biennial and gallery shows across Maine and the Northeast. He shows regularly at ICON Contemporary Art in Brunswick, and one of his favorite installations with his skates was at the former Coleman Burke Gallery in Brunswick, where the skates were displayed on carts with casters and handles, so people could push them through the gallery as a hockey player might move up the ice.

Diana Greenwold, assistant curator of American art at the PMA, worked with Hewitt on the exhibition and came to appreciate the expanse of his interests. She chose objects that were just beyond the obvious and that demonstrated the skills of a craftsman and the vision of an artist. “It’s a great and diverse body of work,” Greenwold said. “Duncan has an economical eye, and my aim was to get a sense of the quirky things that tickle him and lead to work.”

After graduating from Colby in 1971, he left Maine for the University of Pennsylvania, where he received his master’s in 1975. He was working in a boatyard in East Boothbay when USM art department chair and longtime Maine arts educator and artist Juris Ubans hired him to teach at USM. He’s lived in Hollis 38 years, in a house with 6 acres, where he and his ex-wife raised four kids.

They’re all grown now, either in college or out in the world. He’s a grandfather, with another grandchild on the way. One daughter, Caroline Hewitt, followed her father into the arts, and works as an actress. She appeared at Portland Stage in 2012, and recently made her debut at Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. Her biggest claim is appearing on video as Mary Lou in the David Bowie musical “Lazarus” at New York Theatre Workshop. “It’s a tiny part,” her proud father said, “but it’s still pretty cool.”

His studio is a large workshop a short walk from the house. It’s mostly empty, because so much work is on view at the PMA and Hewitt is between projects. He is casting about for ideas and playing with models and concepts. He’s learned to trust his instincts as an artist. “I’m pretty passionate about my doubts,” he said. “You have to listen to yourself.”

Hewitt works mostly by hand and keeps a small collection of chisels and mallets and hand tools. There are vices and anvils, and block of woods are piled to the side of a work bench.

Hewitt has always liked working with wood and attributes some of his early interest to a shop teacher who pushed him. Wood has been a constant, bridging the kind of craftsmanship required to succeed in the boatyards of East Boothbay and the vision and personal stylings required of an artist. Both kinds of work require skill, trust and instincts – and a certain touch.

Those are the same qualities that help a player succeed at hockey.

As it turns out, Hewitt passed on the game of hockey he had been debating, and felt guilty doing so. Especially this winter, good ice is a rare thing. He hated giving it up.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story