Gary Cross was beyond great pain by the time he drove to the Waterville police station to end his life the evening of Dec. 7.

He had done everything possible to try to fix his failing financial situation, which started after his 22-year business selling software to the construction industry went belly up because the software manufacturer for which he was a dealer was sold.

But the more he tried to repair his finances, the more deeply he fell into debt and the more hopeless he became.

He had landed his first job at 16 and worked hard all his life, built a beautiful home for his family on a Troy hillside, had perfect credit and never was late on any payments.

Cross, who said in an interview Thursday that with his “type A personality,” he did not know how to negotiate what he deemed as failure on his part.

On Dec. 7, a Monday, he sat down and wrote a letter to his wife, explaining what she needed to do once he was gone.

“I put everything I could in order and made all the arrangements,” he said. “I left her a note. I left a note for the family in general.”

Cross, 58, of Troy, drove to Thayer Center for Health in Waterville with a handgun and only two bullets — an extra one in case the gun did not fire properly the first time. Once there, he planned to dial 911, explain who and where he was and say that he was going to kill himself.

He chose Waterville — and the hospital — because it was far enough away from his home that his wife would not have to drive by there often and be reminded of his suicide. Hospital personnel would know how to deal with his body, and he wanted to make sure no one else got hurt by a potentially stray bullet.

“I didn’t want anybody to find me that was a nonprofessional,” he said.

What Cross didn’t expect was that the parking lot by the emergency room would be very busy that day. Vehicles were moving around. People were walking. He decided to drive to the police station off Colby Street, as police are professionals and also would know how to deal with his death.

“I drove to the Police Department and found a vacant parking lot and looked around for people,” he recalled. “It was a little lot — no foot traffic, no pedestrians, no people. I called 911 and told them who I was and what I was going to do and where I was, and I’m sure it was a recorded call. I hung up.”

He loaded the two bullets into the gun, got out of his pickup truck and walked about 10 feet to an area where there are trees and brush, being careful to position himself so a bullet would not strike the truck. He wanted to make sure his wife would be able to sell it undamaged.

About to pull the trigger, Cross hesitated. Something was tugging at him.

“I just couldn’t get the picture of my wife and kids and grandkids out of my mind,” he said.

Those thoughts of his family, the professional work of a police negotiator and Cross himself ultimately led him out of danger and into the safety of a hospital that cold night.

But it would take several hours and a lot of talking, prodding and careful work by all involved before Cross would agree to place himself in police hands.

The standoff between Cross and police lasted eight hours, from about 6:15 p.m. that night until he surrendered at 2:45 a.m.

He now is thankful to be alive and back with his family.

“We’re all very close and I just love them to death,” he said.

CREATING POLICE STANDOFF

Waterville police summoned Cross for creating a police standoff, a civil offense, for which he is being asked to pay about $12,000 restitution for the police and emergency workers’ hours involved.

Police and fire officials closed off the perimeter of the police station where Cross was parked Dec. 7 and into the early morning hours of Dec. 8. Officials blocked off side streets, sidewalks and other walking areas around Colby Street and College Avenue, as well as Main and Front streets. Nearby Burger King and Dunkin’ Donuts franchises were evacuated and the Mid-Maine Homeless shelter, within sight of the police station, was locked down.

State police responded with a tactical team, trained negotiators and an armored vehicle.

Cross says he does not blame police for responding but thinks it was excessive. While he acknowledges he caused police to respond, he is worried that others in a similarly desperate situation might not try to seek help if they see what a huge response it would draw and that they might have to pay restitution.

“I just hope that it hasn’t caused any harm to anyone in the future who needs help,” he said.

Cross said he also wants people to know that, while police had to take precautions to make sure no one else was hurt, he never would have shot or hurt anyone else and that he planned to shoot only himself.

“I made it so clear, and the negotiator knew that very clearly,” he said.

Cross is scheduled to appear at 8:30 a.m. Feb. 2 in Waterville District Court. He said he will be represented by Richard Silver, of Bangor. Silver was not immediately available for comment via phone Thursday afternoon.

Waterville police Deputy Chief Charles Rumsey said Thursday that the size and length of police response in the case was necessitated by choices Cross made that night.

“The Waterville Police Department has a history of responding to and working well with people who are experiencing mental health crises, and in helping them to receive the help that they need, and will continue to do that,” Rumsey said.

Cross said he never imagined his actions would draw such a response, and he was not aware so many police officials were present and out of his view that night. He also does not blame anyone but himself for his actions.

“What I did was under tremendous stress and duress, and this is something that was completely wrong,” he said. “It was terrible for my family, for the people that love me. It was horrifying for me. I just couldn’t see my way forward on that Monday.”

He said having been self-employed all his life and paying all his bills on time and then having his livelihood disappear prompted him to take money from savings and try to reinvest to become stable financially, but try as he might, it did not work.

“I was just so overwhelmed to think that I had made so many mistakes so quickly,” he said.

Cross said he wants to clarify something that has been said but is inaccurate — that he walked out of the area where his truck was during the standoff. He said he never walked farther than 15 or 20 feet from his truck except when the situation ended and he unloaded his gun and walked toward a police loudspeaker with his hands up.

Police initially spoke with Cross via loudspeaker and then connected with him on his cellphone. He did not answer it at first because he knew he would see text messages from his family and photos of his children.

Police finally made contact with Cross about three or four hours after the standoff began, Waterville Chief Joseph Massey said early the next morning.

When Cross finally did answer, he found a sympathetic ear in a police negotiator named Jackie, he said.

“She was a great person. She worked very hard. She was very professional. She did the very best she could under the circumstances, but she didn’t know me. I was just another voice on the end of the phone.”

PICKING UP THE PIECES

Cross said he always had been able to provide for his family, and when the financial trouble started, he and his wife, a full-time nurse, could not travel to Colorado to visit their daughter and son-in-law, who is like a son to them, and their two children, as well the Crosses’ son, who also lives in Colorado.

“My wife has just been so sad for so long because she misses them so much,” Cross said.

He said he thought if he were out of the picture, she would be able to be with her children and grandchildren. And with his business gone, he figured no one would hire him, as he is 58 and has only about a year and a half of college.

After the police standoff, Cross was admitted to MaineGeneral Medical Center in Augusta, where he remained two days. He said he felt ashamed of what he had done.

His family came from Colorado, and they and his wife surrounded him with love and support. There could have been no better medicine for him at that point, he said.

“They all came to see me, and the people at MaineGeneral were awesome. My family stayed with me four or five days because they wanted to make sure everything was good and they helped me. My daughter and her husband and grandchildren flew back to be here again over the New Year’s holiday.”

Jenna Mehnert, executive director of NAMI Maine, said she is working to advocate for Cross in his court case.

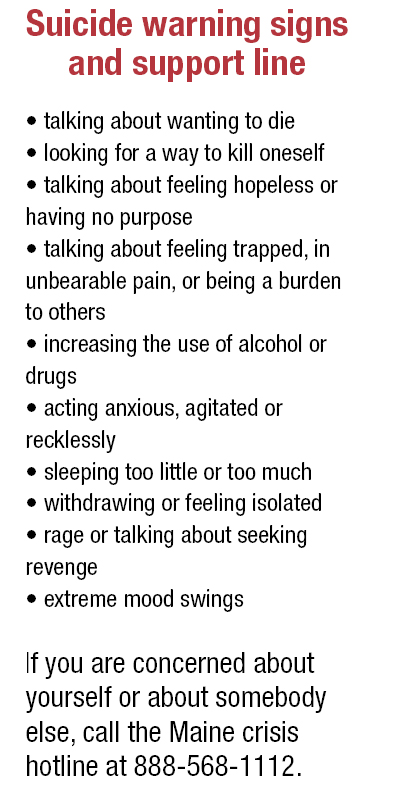

Mehnert said that in Maine, men ages 35 to about 60 are at high risk for suicide, and that is often because Maine is a rural state with a challenging economy. While many people think of those who commit suicide as having a mental illness, Cross’ situation shows that there can be other triggers, such as those related to economic problems.

“It’s completely heartbreaking and unfortunate for Gary that he got to this point,” Mehnert said.

But his situation does challenge the perception of who dies by suicide, she said.

“A Mainer dies by suicide every day and a half,” she said. “Every two weeks, that person is under the age of 25.”

NAMI Maine is working with the Centers for Disease Control on high-risk suicide prevention, according to Mehnert.

Elderly people — especially men who have lost a spouse — also are at high risk for suicide, she said.

Cross has sold the truck he drove to Waterville that night. He had bought it in 2013. He also has sold some other items and is working with his attorney on his financial situation.

“I’m doing everything I can to get back to simple basics.”

He said he will start to look for a job and is not sure what that will be. Before having his own business, he sold West Bend products, including cookware and crystal, door-to-door for 11 years.

“I really need to start over because my reputation, of course, is at stake right now, and for the first time in my life, I don’t have a job,” he said. “I need to get out there and do some hard work.”

Amy Calder — 861-9247

Twitter: @AmyCalder17

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story