The Portland Pipe Line, built 74 years ago to provide for the safe transport of crude oil to Quebec at a time when German U-boats were patrolling the western Atlantic, may be obsolete by the new year.

That would mean fewer oil tankers calling on Portland Harbor and less work for tugboats, harbor pilots, line handlers, marine fuel suppliers, ship agents and ship chandlers. It could eventually mean the loss of more than 30 jobs at Portland Pipe Line Corp., and the mothballing of the Portland Pipe Line facility in South Portland, including 23 storage tanks, assessed at more than $45 million.

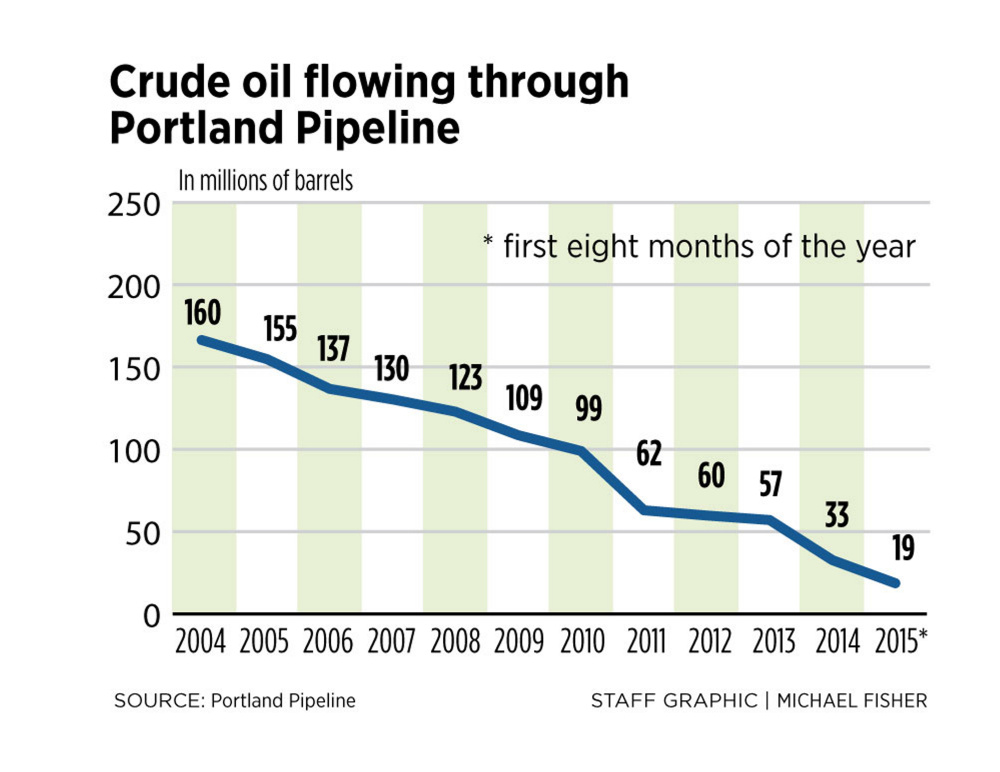

The amount of oil flowing through the pipeline has been dwindling for years, but the completion next month of a major pipeline reversal project in Canada could soon leave the 236-mile line without a purpose, causing speculation that its majority owner, Imperial Oil, will finally shut it down.

“The situation has been coming for a while,” said John Auers, executive vice president at Turner, Mason & Co., a Dallas petroleum industry consulting firm. “It’s here now.”

On the Portland waterfront, people are speculating when the last oil tanker will make the last crude oil delivery at the Portland Pipe Line terminal in South Portland, said Charlie Poole, whose family owns Brown Ship Services.

The number of ships calling at the terminal has been declining in recent years. In the past 12 months, Poole said, the business supplying ships with food and equipment has dropped off 50 percent. That’s why his company is getting out of the ship-supply business and will only provide services such as removing trash.

“With fewer and fewer ships, why should we have people and equipment for something that is not happening very often?” he asked.

HISTORY REPEATING ITSELF

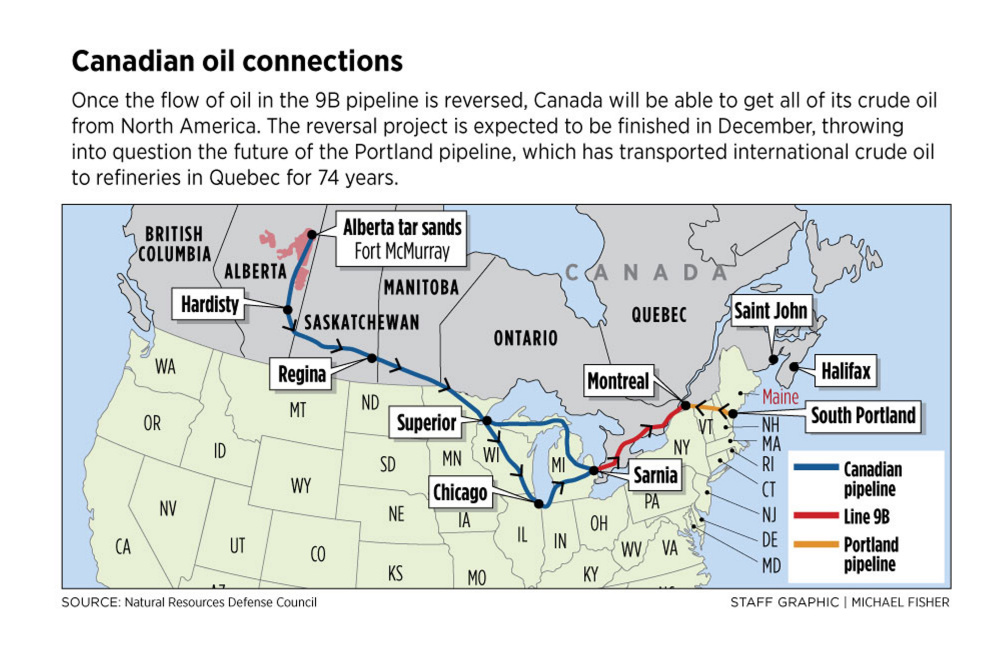

Events in Canada are driving the dwindling flow of oil – a repeat of what happened to Portland Harbor in the years following World War I, when infrastructure investments in Canada toppled Portland from its position as Canada’s winter port. Canada built modern ports in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Saint John, New Brunswick, and allowed for improved rail connections. At Portland Harbor’s peak in 1916, 227 vessels departed the harbor with cargo, primarily Canadian wheat carried here by rail. By 1932, almost all of that business was gone.

Built in 1941, the Portland Pipe Line allowed the harbor to reinvent itself as an oil port.

The oil tanker Sparto carries crude into Portland Harbor on Saturday. Sandy Fielden, director of energy analytics with a Texas consulting firm, said that with shifts in the marketplace and changes in Canada’s needs, Portland Pipe Line is on the verge of becoming redundant. “It’s not absolutely dead and buried,” he said, “but it’s looking like a distressed asset.”

It was mostly built alongside the existing right of way for the same rail line that carried Canadian wheat from Montreal to Portland. There are actually two pipelines, a 24-inch line now in operation and an 18-inch line that was put out of service because of lack of demand. The line is filled with nitrogen gas, which displaces oxygen to prevent internal corrosion. The lines travel 3 feet underground on the route between South Portland and Montreal.

Tankers deliver the oil at the company’s Pier 2 terminal, located in South Portland between Bug Light and Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse. The terminal has 52 feet of draft and is capable of handling some of the largest vessels on the East Coast.

The Portland Pipe Line’s oil flows surged from 1998 to 2008. In 2004, 160 million barrels of oil flowed through the pipeline. By then, Portland had become the second busiest port by volume on the East Coast, behind only Philadelphia. At the peak, there were 24 tankers a month calling on Portland, said Brian Fournier, president of Portland Tugboat.

In 2014, only 33 million barrels flowed through the pipeline – a 79 percent drop. But the flow of oil has declined since the Great Recession because of changes in the oil market. Competition and consolidation have closed five of the six Montreal refineries. The last refinery, Suncor Energy, which for years relied on foreign oil shipped through the Portland Pipe Line, has recently switched to receiving oil from western Canada and North Dakota. The refinery has been getting the Canadian oil shipped by rail.

Only about two tankers a month are now calling on Portland Harbor to deliver oil bound for Quebec, said Fournier.

In September, the last month for which records are available, just under 594,000 barrels of oil flowed through the Portland Pipe Line, down from 2.2 million in September 2014, a decline of 73 percent.

“It’s a ghost town,” Fournier said of the Portland Pipe Line terminal near Bug Light. “It’s the Dust Bowl of the harbor.”

FLIPPING THE SWITCH ON FLOW

It could get even quieter next month when the long-anticipated project to reverse the direction of oil flowing through a pipeline in Canada is scheduled to be completed.

On Sept. 30, Canada’s National Energy Board awarded the final permit to the Canadian pipeline operator Enbridge to reverse the flow of a section of its pipeline known as Line 9B between Montreal and Ontario.

The $82 million project will allow Enbridge to bring 300,000 barrels a day of Western Canadian and U.S. Bakken oil to Quebec. The primary customers will be Suncor Energy’s Montreal refinery and Valero Energy Corp.’s plant near Quebec City.

When the Line 9B project is completed, the refinery, which has the capacity to refine 137,000 barrels per day, will be able to source all of its oil from North America, including the option of taking heavy crude from its own oil sands operations. Suncor is a major producer of tar sands oil, which is a mixture of heavy crude oil, sand and water. Alberta happens to have a vast supply of the oil sands, giving Canada the world’s third-largest crude oil reserve after Saudi Arabia and Venezuela.

Suncor spokeswoman Nicole Fisher declined to discuss in any detail where the refinery plans to source its oil.

“Line 9 will provide supply options as well as access to inland crudes,” she said in a statement. “This in turn will enhance the long-term competitiveness of the refinery.”

Sandy Fielden, director of energy analytics with RBN Energy, a Texas consulting firm, said he believes that Suncor intends to completely stop importing foreign oil, leaving the Portland Pipe Line without any customers.

That would mean Algeria, Nigeria, Angola and Norway – which collectively exported to Quebec an average of roughly 165,000 barrels of oil per day through the first eight months of the year, will have to find new markets. About 60 percent of that oil for the first eight months of this year was carried by tankers up the St. Lawrence River, and the rest traveled through the Portland Pipe Line, according to data tracked by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection and Statistics Canada.

The Portland Pipe Line Corp. is a subsidiary of Montreal Pipe Line Ltd.,which is owned by three oil companies: Suncor Energy, Shell Oil and Imperial Oil, which is the majority owner. Suncor owns 23.8 percent of the pipeline company.

Suncor’s plans for sourcing oil will become apparent within a matter of weeks. Enbridge has completed hydrostatic tests of Line 9B – which involve filling the pipe with water at high pressure to ensure there aren’t any leaks – and is now filling the pipe with oil for service by the end of the year, Enbridge spokesman Graham White said.

Auers said Suncor may decide to continue to buy oil through the pipeline – at a reduced volume – so the pipeline infrastructure can be maintained and give the company future options if the market changes and imported oil becomes cheaper than domestic oil.

“It would not be out of place or unprecedented for Suncor to commit to a certain amount of volume to keep supplies from the West honest,” he said. “You always want to have more than one place to get your crude from.”

Even so, the Portland Pipe Line is not the only source of oil via the Atlantic Ocean. Suncor will still be able to get foreign oil shipped by tankers up the St. Lawrence River. The one constraint is that the St. Lawrence River is only kept open for shipping as far west as the Port of Montreal in the winter with the help of icebreakers, so tankers with strengthened hulls would be required to navigate to Montreal, said Fielden of RBN Energy.

In addition, TransCanada Corp. plans to build a 2,734-mile pipeline to connect oil fields in Alberta with the Irving Oil refinery in Saint John. The Energy East pipeline would bypass Maine to the north and give Canada a path to export its oil reserves without crossing an international border.

Fielden said the Portland Pipe Line is on the verge of becoming redundant.

“It’s not absolutely dead and buried,” he said, “but it’s looking like a distressed asset.”

FUTURE USES UNCLEAR

One possible use for the pipeline, he said, is reversing the flow, giving Canada access to an ocean port and international markets. President Obama’s decision early this month to reject the proposed Keystone XL pipeline, which would have carried oil from Canadian oil sands to refineries on the Gulf Coast, creates an opportunity for the Portland Pipe Line because it would provide another international pipeline route to a seaport, he said.

“There’s a lot of crude in Canada looking for a way to reach the water right now,” Fielden said.

But the South Portland City Council approved an ordinance last year that effectively prevents the company from reversing the flow of the pipeline.

Oil sands requires more energy to get out of the ground, process and refine, making it a target of environmental activists around the world.

Portland Pipe Line is now suing the city in U.S. District Court in Portland, claiming that the ordinance is unconstitutional because it interferes with interstate trade, discriminates against Canadian interests, devalues the pipeline and infringes on areas of regulation best left to the federal government.

Eben Rose, who opposes any attempt to reverse the pipeline and won a seat on the City Council in November, says it’s time to consider other uses for Portland Pipe Line’s industrial facilities and tanks.

He envisions the city and Portland Pipe Line joining forces to transform the industrial facilities and tanks into offices and laboratories for a research institute that would focus on finding sustainable ways to create energy, such as using algae to refine petroleum.

The pipeline itself, he said, could be a conduit for underground transmission lines carrying electricity produced by hydropower plants in Canada.

“We have to repurpose it and find creative ways of using new technology,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story