FREEPORT — When she’s alone in her home with the small owls she catches, Judy Camuso talks to them.

An owl bander of 20 years, Camuso won’t reveal exactly what she says to the northern saw-whet owls that she nets behind her house and bands in her kitchen. But when it’s just her and the owls, Camuso reassures them, simply because she’s accustomed to speaking when they’re there.

At times Camuso shares her banding work, as well as the visiting owls, with public groups in her kitchen.

“I’ve been banding for 20 years and giving public programs on it here for 19,” said Camuso, Maine’s wildlife division director. “Every year I say I’ll stop. But I’ve spent almost half of my adult life banding owls. It’s all I’ve known in the fall.”

Every year for eight weeks, Camuso bands owls each night for the U.S. Geological Survey Bird Banding Laboratory. There are fewer than 30 federally licensed banders in Maine, and only a few spend time in the fall banding saw-whet owls. Most of her fellow banders involved in the study are in other states or provinces along the bird’s migration route, including Nova Scotia, New Jersey and Georgia.

The owls need to be banded because scientists know little about their life history and habits. When Camuso started to help licensed banders 24 years ago, she realized basic data, like how long a saw-whet owl can live, was unknown. She felt compelled to help gather more data by learning to catch owls, handle them and attach the small metal clasp used in the study around the legs.

The numbered clasp is the key to the study, providing information at the time an owl is recaptured,where it came from and how long it’s traveled.

Camuso, 44, has always turned the volunteer banding work she does into a public program for various groups. Two weeks ago 13 members of the Royal River Conservation Trust were treated to the homegrown owl show. That night Camuso caught four owls. Not bad for an off-peak week.

“She has a room full of people here who are totally captivated,” said Mike Carroll, 45, an environmental science teacher at Scarborough High. “My wife is jealous I got to come with my daughter. My students are jealous of me that I’m here. I can’t wait to share this with them tomorrow.”

Each fall Camuso bands about 200 saw-whet owls, birds that weigh 2 to 3.5 ounces. She also may band other birds that fly into her four nets.

She opens the nets for about four to seven hours each night and checks them every 45 minutes. It’s a balance, Camuso explained. If she checks the nets too often, the owls will sense too much activity and avoid her woodlot. If she waits too long, they could grow stressed or fall prey to bigger owls.

When she nets an owl, Camuso untangles it and puts it in a small cotton bag to calm the bird. She takes the bags to her kitchen where she holds the owl by its talons as she takes measurements and records data.

With an assortment of wooden chairs and benches lined up in rows, Camuso’s kitchen becomes a makeshift classroom as she works on the birds. A dozen adults and children sat there two weeks ago in silent awe.

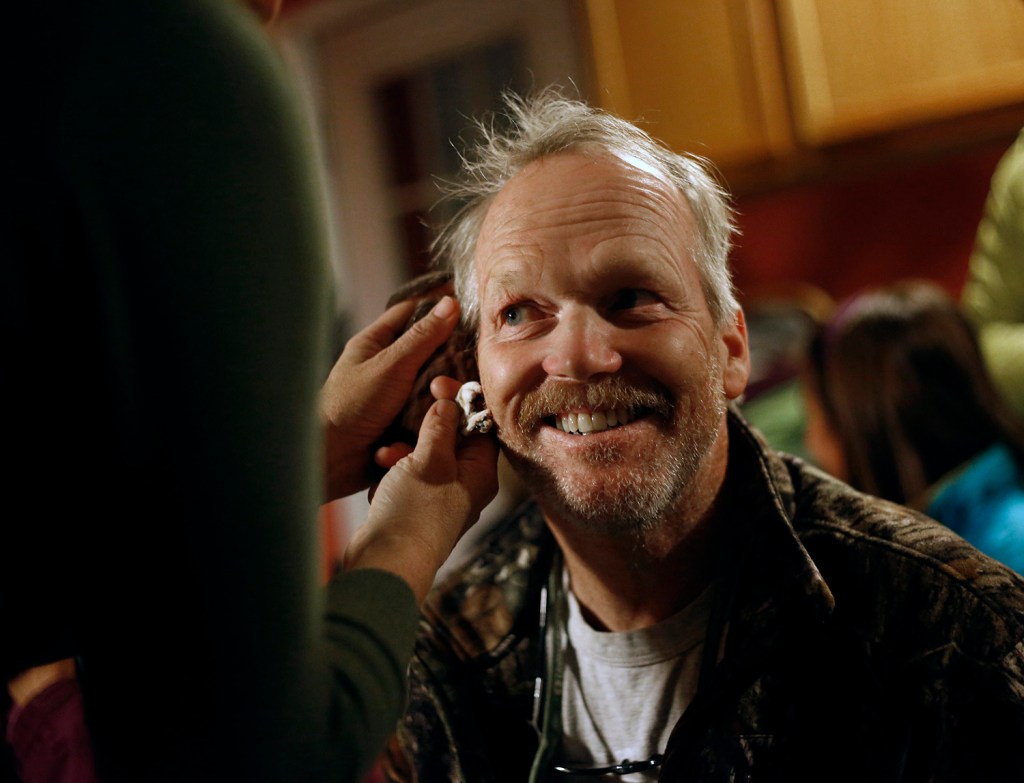

Then Camuso carries the owl around to let each guest hear its heartbeat. The entire room is full of smiling people.

“It never gets old,” said Eugenie Francine of Freeport, who had been to Camuso’s owl banding several years ago. “They’re adorable. What I love is everyone’s expression. It’s contagious. People love owls.”

Then comes time to release the owl, and Camuso goes outside alone with it, leaving her guests in her darkened kitchen so that the lights don’t draw the bird back.

Her guests, mostly strangers, sit together in darkness. Yet strange and unexpected as the owl-banding protocol is, the group is left transfixed and moved by the experienced.

“I was surprised to learn they don’t know that much about the owls. I thought she’d have all the information and be able to see a pattern,” said 11-year-old Olivia May Carroll, the science teacher’s daughter.

“Being an owl lover, I think it’s really cool that she does this for fun. I want to do this someday.”

In fact, there remains little biologists do know about this tiny bird despite the fact that banders like Camuso have been contributing annual data for decades.

“How long lived are they? We don’t know. People thought they used the coast for migration but that’s not the case,” Camuso said. “You’d think by now some of these things would have easy answers, but the recovery of the (banded) birds is not great.”

And yet Camuso knows her 20 years of data reveals some trends, insights and stories.

One day, she promised, she’ll analyze her own data and contribute to science a greater understanding of this small bird.

“Every year I say it’s too tiring. Then come May, I say maybe one more year. Most likely I will keep doing it,” she said. “It’s such a part of my life. I started as a volunteer before I got my banding license at 24. And I like sharing it with people. But when I’m by myself, I talk to the owls.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story