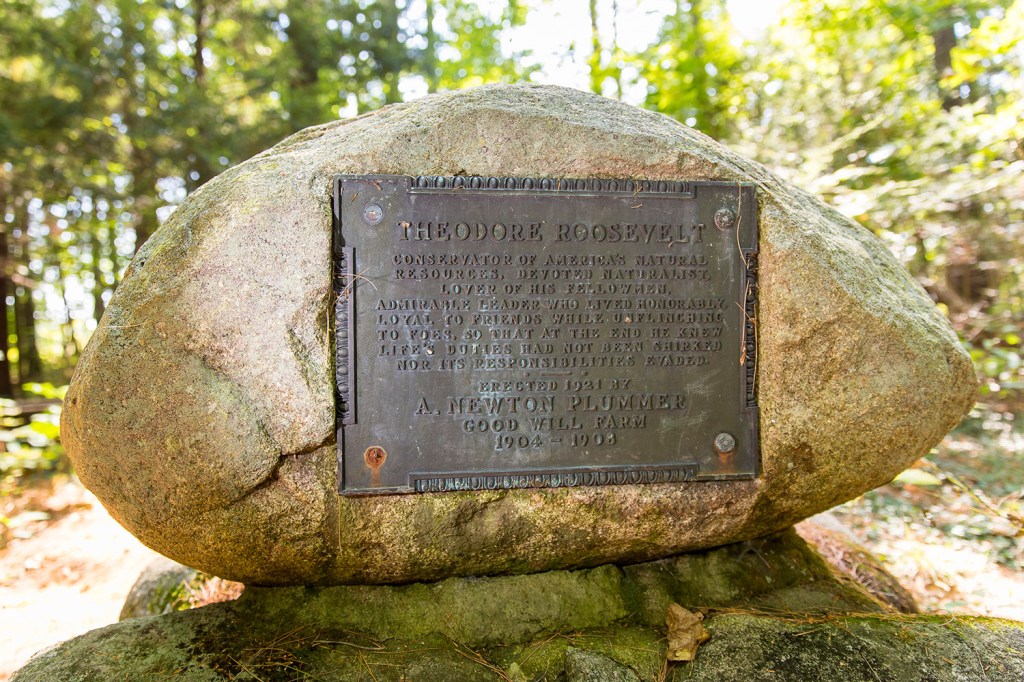

HINCKLEY — The 3-foot-high cairn dedicated to Theodore Roosevelt, the stone tower complete with a spiral staircase and the stone pillars dedicated to the Dartmouth Outing Club are just some of the monuments along a century-old trail that celebrates the spirit of the Good Will-Hinckley School and its founder.

After George Walter Hinckley opened the school in Hinckley – about seven miles from Exit 133 on Interstate 95 in Fairfield – for underprivileged children in 1889, he tried to inspire students to spend more time in the woods by creating a forest trail peppered with monuments and strange pillars. He believed nature was a learning tool, and his ideals are expressed along the Dartmouth Trail, which the school’s L.C. Bates Museum is celebrating this year as the trail turns 100.

“He believed in education through play outside. He was ahead of his time. He was into Next Gen back then,” said museum educator Melissa Bastien, referring to Maine’s new academic initiative – the Next Generation Science Standards – that encourages experiential learning.

Along the Dartmouth Trail, Hinckley placed elaborate and whimsical monuments to give students a “destination” when they were hiking.

“Monuments are valuable because, first, they take us into the past and show us why we should be grateful; second, they inspire us to emulate the examples memorialized; and, third, they beckon us into the future,” said Hinckley, who died in 1950 at age 97.

As the Dartmouth Trail celebrates its centennial this year, the curators at the school’s history museum say it hasn’t lost its draw for Hinckley students or those who visit from other schools.

“We use this space a lot,” Bastien said of one of the trail’s two outdoor classrooms that offer benches and tables. “There are children in Augusta who have never been in the woods. And we live in a forested state. They come here and swallow these lessons in huge chunks.”

Honored by the elaborate stone monuments along the trail are President Theodore Roosevelt, one of the nation’s first conservationists, and Ernest Thompson Seton, one of the founders of the Boy Scouts of America, who visited the school in 1912.

The stone seat honoring Seton sits in an amphitheater that most years is used for the school’s opening ceremony, said alumnus and Hinckley historian John Willey of Waterville.

Hinckley’s son, Walter, planted the Dartmouth Trail’s “avenue of pines” that takes hikers out of the thick woods and along a wide sunny path lined by thick 90-year-old red pine trees.

“This was one of my favorite places to visit,” said Willey, who attended the school in the 1940s. “Back then there was no TV, very little radio, no computers. Our entertainment was the outside world.”

At the trail’s terminus is a round tower designed like a pulpit and dedicated in 1920 to one of Hinckley’s personal heroes: Adirondack Murray, an author and preacher who was considered by many at the time to be the grandfather of camping.

“Mr. Hinckley believed recreation was important for children, it was part of his philosophy. To be on the trails in the woods was healthy for children,” said museum director Deborah Staber.

“Adirondack Murray influenced Mr. Hinckley with this way of thinking. So did John Muir, who was another contemporary.”

Parts of the school’s arboretum, named Sunset Park, were designed by the Frederick Law Olmsted firm, which designed Central Park in New York City and Deering Oaks park in Portland. The Dartmouth Trail is just shy of a mil, and is part of the four-mile trail system in the arboretum.

The trails begin behind the museum and are both free and dog-friendly. They’re well-worn and well-blazed, thanks to generations of Hinckley students who learned and explored along the trail.

Photos of Hinckley standing along the Dartmouth Trail hang in the museum. Dressed in the three-piece suits of the time, he looks stoic as he stands upright next to his monuments. But those who knew the school’s founder say he was warm and approachable.

“He was a kind man, and a man ahead of his time. My claim to fame is I got to shake his hand when I was 9,” said Willey, 82.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story