Is a hamburger made from grass-fed cattle raised on a small farm in Maine a more ethical choice than one made from Midwestern feedlot beef fed GMO grain? Locavores may say yes, but James McWilliams strongly disagrees.

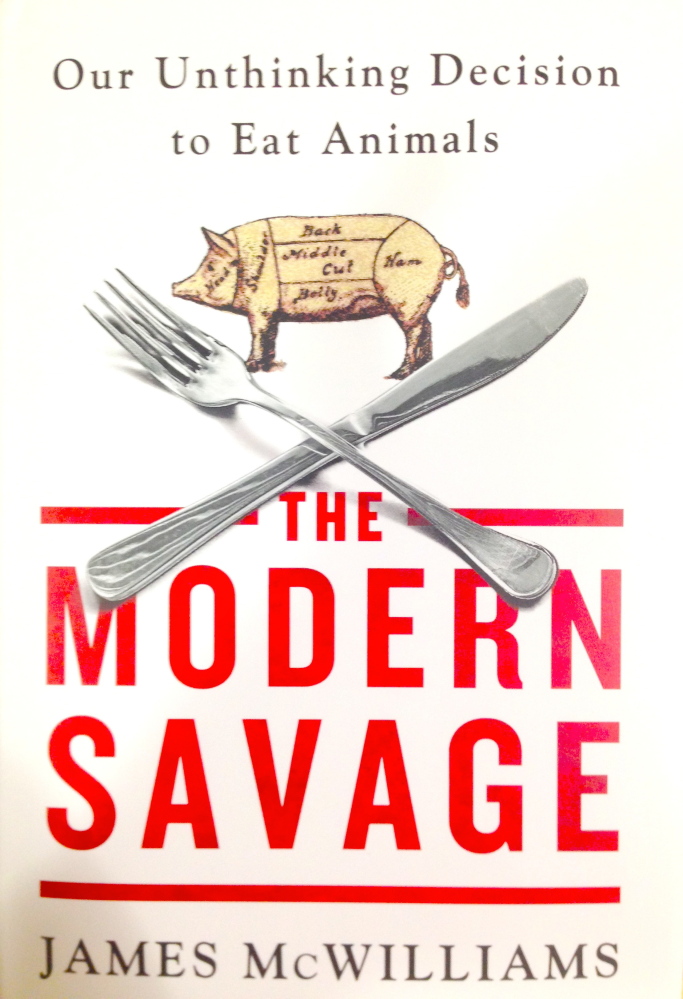

McWilliams, a history professor at Texas State University, is the author of the provocative new book “Modern Savage: Our Unthinking Decision to Eat Animals,” which was published in January by St. Martin’s Press.

The book challenges the conventional wisdom surrounding small livestock farms and provides a critical examination of what he sees as our culture’s largely unconscious tendency to gloss over and ignore the unsavory side of meat consumption – on both factory and family farms.

A review of the book in the Chicago Tribune called McWilliams a “contrarian” who likes to “mock sustainable farms.”

In contrast, The Huffington Post said the book is a “game changer,” and Science News called it “thought-provoking.”

In “Modern Savage,” McWilliams contends that chickens, beef cows and pigs raised on small farms foster what he calls the “omnivore’s contradiction.” He defines this as “our aspiration to grant animals moral status and yet eat them.”

He goes on to write that buying meat marketed as more sustainable provides “privileged consumers with the false sense that they are doing something meaningful to reform the food system” without questioning the underlying assumptions of an animal-based diet and what it means for billions of animals or the environment.

The marketing of local meat as an alternative to factory-farm meat, he writes, allows industrial farms to “thrive in the business of providing cheaper and more accessible products for the vast majority of consumers.”

To back up his claims that small-farm life isn’t all green grass and sunshine, McWilliams quotes from farmer chat rooms and blog posts written by homesteaders. The picture he paints isn’t pretty.

The small-farm problems he documents include botched backyard slaughters, withheld veterinary care, painful practices such as nose rings for pigs, gruesome deaths from predators, castrations without painkillers and calves sold from their mothers.

McWilliams also examines the environmental and physical limitations of the idea that Americans could or should replace the factory-farm meat they eat with a locally raised, grass-fed alternative.

When it comes to beef, McWilliams points out, most herds of grass-fed cattle are actually fed grain at some point (often in a feedlot).

He also gets out a calculator to discover that if all U.S. cattle were raised in pastures it would require almost all of the available land in the United States. Because of this, McWilliams argues, only an elite few can and ever will be able to afford grass-fed beef.

He takes well known food writers such as Michael Pollan and Mark Bittman to task for wobbly ethics when it comes to advocating eating fewer animals, but still eating some.

For instance, he writes: “Rather than acknowledging that vegans eat in a manner that’s morally consistent with the core assumption that animals suffer when killed, Pollan doesn’t just dodge the thorny question of killing animals he claims to care about. He encourages his readers to dodge it as well.”

In today’s locavore-leaning food world, McWilliams’ arguments are not always popular.

He is generally ignored by mainstream food writers (although grass-farm guru Joel Salatin wrote a rebuttal in 2012 to McWilliams’ ideas), loved by animal advocates (PETA praises the book), criticized by hardcore vegans (who’ve assailed him for placing cows and crickets in different moral categories) and often embraced by conventional farming publications (AgWeek gave the book a favorable review).

When I reached him at his office in San Marco, Texas, McWilliams told me he’s disappointed that the mainstream food culture is mired in an ideology of “culinary libertarianism” and prefers to ignore tough questions about whether small-scale animal agriculture is any more sustainable than large-scale animal agriculture.

“The bigger issue is this notion that eating local (meat) has some environmental benefit,” McWilliams said. “But if you look at the evidence, there’s very little research to support that.”

While the wider food world isn’t ready to tackle such big ideas, he sees more intellectual heavy-lifting taking place on campus, where he co-teaches an honors course called Eating Animals in America.

“It fills up within a matter of minutes,” McWilliams said. “It’s one of the hardest classes to get into.”

The university even lists the course in its glossy promotional mailer sent to high school students.

“We don’t see a whole lot of changes in people’s diets” during the course, McWilliams said. “But we see a whole lot of thinking about it.”

After teaching the class for four years, McWilliams said even his thinking around what he eats has changed.

Now the ultra-marathoner and former vegan calls his diet vegan-ish, because he eats energy bars made with cricket flour.

“Eating insects can be ethically justified far more easily than eating a land-based animal,” said McWilliams, who adds that there is a “fascinating movement around eating roadkill.”

While McWilliams feels a case can be made that it is ethical to eat insects and roadkill, he says the moral arguments fall apart when it comes to farm animals.

“We have to fight a strong fight against all animal domestication,” McWilliams told me. “Every problem with our food system now and historically leads you to domesticated animals.”

And whether those animals are raised for human consumption on a factory farm or a family farm, McWilliams said the practice presents thorny ethical issues too often obscured by feel-good ideas that dissipate when you shine a light on what life is like for animals who live on farms both big and small.

Avery Yale Kamila is a food writer who lives in Portland. She can be contacted at:

avery.kamila@gmail.com

Twitter: AveryYaleKamila

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story