Noah Jones, 16, had to make an awkward enquiry before entering the Lincoln Academy library one day this spring.

“Is everyone in this room vaccinated?” Noah, of Alna, recalled asking a group of puzzled fellow high schoolers. Noah, a sophomore, has been fighting leukemia for two years and his immune system does not offer him much protection from infectious diseases. A chickenpox outbreak in the community that had infected some students required Noah to take extra precautions.

“When you have barely any immune system protection, something like the chickenpox can be fatal,” said Noah, who must undergo another year of leukemia treatments. “It was really worrying.”

Noah depends on everyone else around him getting vaccinated – the “herd immunity” that lessens the risk that individuals will contract a contagious disease if everyone around them is vaccinated – to protect him from vaccine-preventable infections like measles, pertussis, chickenpox and other diseases.

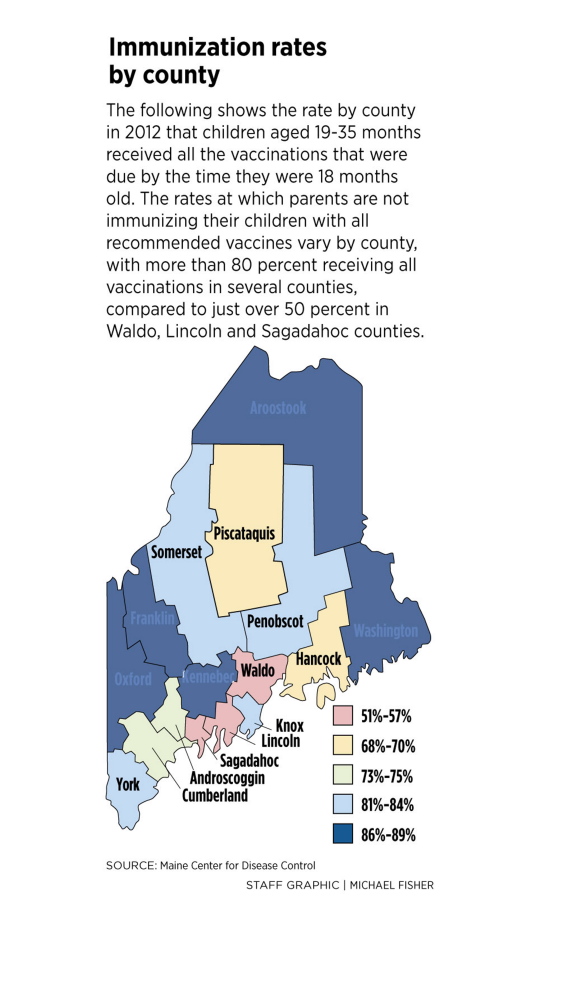

But Maine is one of the most dangerous states for Jones and others with compromised immune systems. The state has one of the highest childhood vaccination opt-out rates in the country, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and it has had an effect: Maine has experienced a surge in pertussis, or whooping cough, since 2013, which experts attribute in part to low vaccination rates. The measles outbreak this winter at Disneyland in California that sickened hundreds and commanded national headlines was traced to people who were not vaccinated.

Maine will take center stage in the vaccine debate Monday when public hearings on a series of bills will be heard in the state Legislature, promising to draw a crowd of anti-vaccine and pro-vaccine advocates. Hundreds are expected to pack meeting rooms, and anti-vaccine advocates have planned a rally at the State House with Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has vocally criticized the safety of vaccines.

The bills span the gamut of positions: One bill would make it more difficult for parents to opt out of vaccinations for children entering kindergarten, while another would weaken vaccine laws.

Parents’ choosing not to vaccinate their children because of unfounded fears – and the resulting consequences for public health – could be devastating, health experts say.

The fact that people are needlessly put at risk for preventable diseases is difficult to deal with, said Cathy Jones, Noah’s mom.

“It’s infuriating and heartbreaking because it doesn’t have to be this way,” she said. “To go through all that we’ve gone through over the past two years, and to think that Noah could get really sick from a preventable illness, it’s mind-blowing that it’s even a possibility.”

But Jones said she realizes trying to change the views of parents who forgo immunizations for their children is a difficult task because their minds are set.

The fact that vaccines work and are overwhelmingly safe is not in dispute among scientists, and a single 1998 study that suggested a link between vaccines and autism has been disproved and retracted.

“All the righteous indignation, sarcasm, hammering away with facts doesn’t do anything, because I’ve done all of it,” Cathy Jones said. “You want to get up on your soapbox and yell, ‘Don’t you realize you can kill my child? What are you thinking?’ But (vaccine deniers) still don’t get it.”

The anti-vaccine movement is rooted in a distrust of the medical industry, experts say, and a mistaken belief that vaccines contain artificial ingredients that are harmful. In addition, some libertarians have argued that the government should not force parents to vaccinate as a requirement for children entering public school, calling it an overreach into how parents raise their own children.

Anti-vaccine advocates have thrown their support behind a bill that would create a new state program to investigate vaccine injury claims, require doctors to read a statement to patients letting them know they could be injured by a vaccine and include licensing penalties for doctors who make “coercive” statements to patients to persuade them to be vaccinated.

The advocates say the bill is necessary because the CDC cannot be trusted, and many skeptics dispute government reports about vaccine safety.

Public health experts have called that bill an unscientific scare tactic.

A NERVE-WRACKING TIME

In Portland, Crystal and Joe Giordano are counting the days until they can get vaccines for River, their 9-month-old son, who is behind on the shots because he was born prematurely and has respiratory problems.

Until then, they’re relying on herd immunity to protect him, a nerve-wracking time for the parents. When fewer people receive vaccines, herd immunity breaks down and leaves more people at risk for measles, pertussis, mumps and other infectious diseases. For some diseases, the effectiveness of herd immunity starts to wane when fewer than 95 percent are vaccinated.

“It is so scary,” said Crystal Giordano as she lovingly gazed at her chubby boy.

Giordano has watched closely the news about the vaccine debates in the Maine Legislature.

If it’s anything like the debate this spring in California – where lawmakers are considering whether to eliminate all non-medical exemptions allowing people to forgo vaccines before children can enter public school – the debate will be impassioned and vitriolic. The sponsor of the California bill had to use a security detail after receiving threats.

Kennedy, who has written a book on the topic and recently came under fire for comparing mandatory vaccinations to the Holocaust, is expected to be on hand Monday for the debate.

OPTING OUT ON PHILOSOPHIC GROUNDS

In Maine, one of the bills that will be heard would require a consultation and a signature from a health professional before parents are allowed on philosophic grounds to opt out of vaccines required for school. Maine’s non-medical kindergarten opt-out rate is 5.2 percent, most of it because of parents using the philosophic exemption.

A similar law that was recently approved in Oregon has resulted in better vaccine coverage, according to news reports.

The Giordanos hope reason and science persuade Maine lawmakers to offer better protection for River and others who rely on herd immunity to stay safe.

Pertussis could be especially dangerous for River, who has reactive airway disease, similar to asthma. Maine’s pertussis rate has climbed in recent years, and in 2014 the state had nearly 500 cases.

“I am deathly afraid of pertussis,” Crystal Giordano said. “His lungs are so compromised, the doctors have told us that pertussis would really knock him out.”

River wheezes often, and had respiratory problems during the long winter, although he will likely grow out of his respiratory issues.

His mother said she worries about the germs being brought home by their 7-year-old son, Angelo, and her husband, who works in the school system and is also a youth coach.

She has started asking parents if their children are vaccinated before scheduling play dates with Angelo.

“I’ve learned to be very brazen,” she said.

But there’s only so much they can do and they don’t want to limit Angelo’s social or educational opportunities out of fear.

“A lot of this is out of our control,” Crystal Giordano said. “We’re relying on the community to protect River.”

The Sturtevant family of Portland has an ongoing concern about infectious diseases.

When Sam Sturtevant was an infant, he was infected with the enterovirus and required a liver transplant.

While the 19-month-old toddler is now healthy and has a promising long-term prognosis, infectious diseases will always be a worry. His condition will not allow him to receive most vaccines, said his mother, Maureen Sturtevant. In addition, the medications Sam takes for his liver suppress his immune system, making him more susceptible to infectious diseases.

“We are entirely reliant on herd immunity going forward,” she said. That worry is already affecting how they approach certain scenarios, such as asking parents whether their children are vaccinated and being vigilant about germs.

“We are surrounded by Purell,” she said.

REFUSING TO LIMIT ACTIVITIES

Noah Jones has responded well to leukemia treatment, but there are no guarantees for his future.

Cathy Jones said they didn’t want to home-school Noah or greatly limit his activities, despite the risks.

She said they know some of the students at Lincoln Academy are not vaccinated, and on some days Noah’s immune system will be more susceptible to diseases.

“It’s absolutely terrifying,” Cathy Jones, 42, said. “But we’re not going to live in a bubble. Noah should get to go to the prom, act in a play, have friends at school.”

This weekend, Noah is acting in a production of “Les Miserables,” a situation that puts him around dozens of kids and performing in a room full of people. When he acted in a play earlier this year, he later found out one of the students involved was not vaccinated, which made him uneasy.

“People who don’t vaccinate don’t think about or realize how easy it is for me to get sick,” Noah said. He said he attributes the anti-vaccination movement to an “unhealthy group mentality.”

“It’s really easy to get caught up in, ‘We’re so very right and the other side is so very wrong,’ ” Noah said.

His mom said she hopes one day trips to the grocery store or bowling alley will not cause anxiety, and that someday the culture will change and everyone will be vaccinated, like they were before the vaccine scares that started in the late 1990s.

“This isn’t just about an individual child,” she said. “This is a moral issue, and a community responsibility.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story