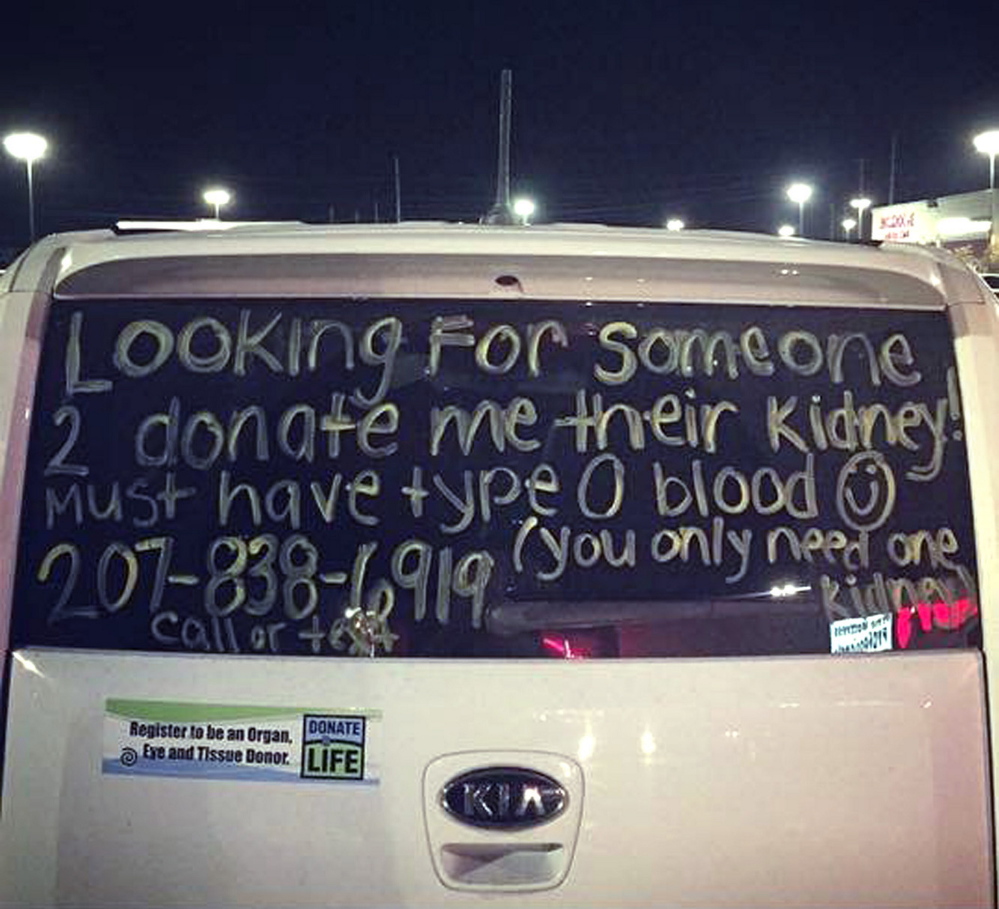

It was the ultimate feel-good story: Christine Royles, a South Portland woman in need of a new kidney, puts her request on her car window, spurring Josh Dall-Leighton of Windham, a man she’d never met, to offer to be a donor. Tests confirmed that he was a strong potential match; surgery was set for May at Maine Medical Center.

Now the operation has been put on hold over Maine Med’s concerns about a fundraising effort for Dall-Leighton. At a news conference on Thursday, hospital officials said they want the transplant to take place, but first they must make sure that no laws designed to prevent the sale of organs are being broken.

However the situation is resolved, this impasse is emblematic of a nationwide problem: the vast shortage of donated organs and the desperation of those in need. There’s no single remedy, but steps can be taken at the federal level to encourage donations and begin to dismantle barriers to helping very sick people.

At issue is an online campaign by a friend of Dall-Leighton that’s raised nearly $48,000 to help support the donor, a father of three, and his family while he’s recovering from surgery.

The average estimated cost of making a live kidney donation is $6,000, including transportation, time lost from work and child care. So although it’s clear that profit is not a motive for Dall-Leighton, what to do with the excess money raised is a major concern, given that federal law bars living organ donors from being paid for expenses before they donate.

Organ recipients are allowed to reimburse donors after the surgery, but this raises another issue. While tens of thousands of Americans could benefit from a live donation, few potential live donors can afford to spend the money first and then await reimbursement.

Bioethicist Sigrid Fry-Revere calls this a “financial disincentive” to donation. She wants to amend federal law to allow a prepaid debit card-based system “enabling government programs, private medical charities and other people to cover donors’ expenses as they occur.”

This is a proposal that deserves further study. While nobody supports dismantling safeguards against allowing rich patients to exploit the poor for their organs, we also must acknowledge that the current system has disadvantages for both low-income donors and low-income recipients.

This is not to downplay the importance of posthumously donated organs. But fewer than 1 percent of people who die each year in the U.S. are healthy enough or close enough to a hospital at the time of death to donate their organs — and 75 percent of this group does so anyway.

So although campaigns to encourage people to donate their organs after death are commendable, they’re not enough to fill the gap. We can’t afford to overlook ideas for increasing the pool of viable live donors if we truly want to help those to whom the gift of an organ may make the difference between life and death.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story