VASSALBORO — Most of the mills built along Outlet Stream centuries ago are gone. Still remaining, though, are several of the dams that went with them.

While the dams provided power to the mills and tanneries along the 10-mile waterway, they blocked the annual migration of alewives, also known as river herring, and other fish from the Sebasticook River south to spawning habitat in China Lake.

Now there’s a move to get the alewives back.

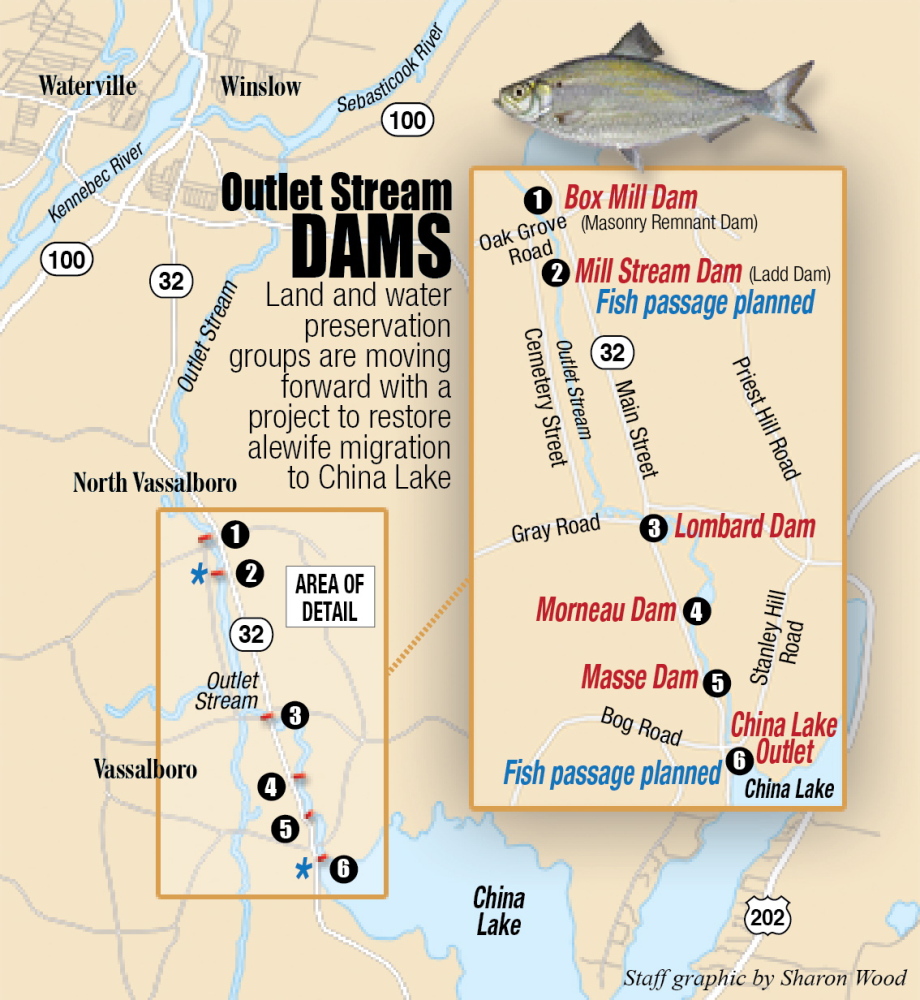

A coalition of conservation groups and government agencies is pushing an initiative to bypass or remove the six remaining dams on Outlet Stream and restore the annual alewife run. The fish have recently returned to the Sebasticook River, which is at the northern end of Outlook Stream, following dam removals.

The project to restore alewives to China Lake, at the southern end of the stream, could cost more than $2 million, but the payoff could be equally huge, proponents say.

Bringing alewives back to Outlet Stream could add up to a million adult alewives to the annual run that comes up the Kennebec River, an at least 30 percent increase to what is already one of the largest populations on the East Coast.

“It’s the greatest population addition to the Sebasticook system outside of Sebasticook Lake,” said Jennifer Irving, executive director of the Sebasticook Regional Land Trust.

While the little fish already plays an outsized role in the marine food chain, the impact of a boost to its population would be big. Based on the experience with other lakes and ponds, restoring alewives could improve water quality in China Lake, which has deteriorated because of high phosphorus levels.

“It’s an opportunity now, with this partnership, to propagate alewives here and reverse the deterioration in the lake we’ve seen for decades,” said Scott Pierz, president of the China Lake Association.

Others, however, are worried that reopening Outlet Stream will expose water bodies to invasive predators that have already taken up residence in other areas opened up to alewife populations.

ECOLOGICAL BUILDING BLOCK

The Alewife Restoration Initiative is a partnership between the China Lakes Region Alliance, Maine Department of Marine Resources, Sebasticook Regional Land Trust, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, China Lake Association, and Maine Rivers.

The state marine resources department has advocated restoring a fish passageway to China Lake since the mid-1980s, when it adopted a strategic plan for restoring American shad and alewife to their historical range.

Before European settlement, virtually every stream on the East Coast hosted an annual alewife run, said Nate Gray, a department specialist on alewives. As human population increased, the passages were blocked by dams.

Over the past two decades, however, the alewives have come back to many Maine rivers, including the Kennebec. The removal of the Edwards dam in Augusta in 1999 and the Fort Halifax dam in Winslow in 2008 let the alewives come streaming back – Gray estimates that about 3 million adult fish now make the journey from the Gulf of Maine to such inland spawning grounds as Sebasticook Lake.

Alewives, which grow to 11-12 inches in length, play a critical role in the marine ecosystem. They are eaten by virtually every other marine fish, mammal and bird, and are commonly used as lobster bait. The more alewives that are introduced, the healthier the overall ecosystem will be, Gray said.

China Lake has the potential to create a gigantic population bump.

“It would be a fairly massive addition,” Gray said. “In the fisheries restoration world, that’s a rare bird.”

Alewives spend most of their lives in the ocean, but return inland to spawn every year. Young fish spend the first few months of their lives in freshwater lakes and ponds before migrating to the ocean. The fish mature at four years, when they return to reproduce.

Considering its size, Gray predicts that by the end of the first four-year cycle between 900,000 and 1 million alewives could return to China Lake every year.

The introduction of so many fish could also restore flagging water quality in China Lake.

Young alewives act like phosphorus sinks, removing phosphorus from bodies of water when they migrate to the ocean. Some studies and anecdotal evidence indicate that presence of alewives results in better water quality.

In China Lake, where elevated phosphorus levels have brought algae and a deterioration of water quality, the reintroduction of alewives could be a game changer. Anecdotally, bringing alewives back to nearby Webber and Three Mile ponds has resulted in noticeably cleaner water, Irving noted.

“We can’t promise that it’s going to happen, but that’s the experience in other lakes in Maine,” she said.

Phosphorus, a necessary element, can choke plant life in a lake when there’s too much of it. Development along lakeshores, fertilizer seeping into lakes, and human waste all lead to high phosphorus levels.

Cleaner water would be a relief for those who live near and use the pond, but it might also help the 22,500 customers of the Kennebec Water District from Waterville, Winslow, Fairfield, Benton and Vassalboro who rely on the lake for their drinking water.

“It would be great to think that in my lifetime, through this initiative, we could see the water quality turn around,” said Pierz, the lake association president.

Jeffrey LaCasse, the water district’s general manager, said that it has commissioned a study to determine if the theory that alewives will contribute to water quality holds true. If the results are positive, the district may decide whether it should contribute resources to the effort, LaCasse said.

Last year the marine resources department stocked China Lake with more than 21,000 adult alewives. The adult fish will try to return, giving restoration efforts a head start, Gray added.

But if anyone needed proof that the fish want to be in the lake, they only need to witness the thousands of alewives that collect in the small pools below the first dam on Outlet Stream each spring trying to get upstream.

The fish want to find new habitat, and are following age-old runs, Gray said.

“We are not introducing fish into non-historic habitat,” he said.

For restoration to occur at all, the barriers posed by six remaining dams on Outlet Stream have to be addressed.

UNFRIENDLY COMPANIONS

About three miles north of the lake is Box Mill dam, followed in relatively quick succession by Mill Stream, Morneau, Masse and finally China Lake Outlet dams.

“They are all obsolete,” Irving said of the dams. “They are really just barriers at this point.”

The coalition is negotiating with dam owners with the aim of removing most of the dams entirely, Irving said. In some cases, the barriers are little more than rubble, remnants from an earlier era.

But at China Outlet and Mill Stream, new fish passageways will be installed. The China Outlet dam, at the source of the stream, is used to adjust the lake’s levels and can’t be removed.

Mill Stream and its waterfall, on the other hand, is a public recreation area, said Ray Breton, the dam owner.

In early conversations with organizers, he made it clear that he was in favor of the alewife project, but also that Mill Stream dam couldn’t come down, Breton said.

“I’m for it all the way, but there is a way to get around the dam without removing it entirely,” he said. “I don’t want to lose the falls.”

Other dam owners are also working out arrangements with the initiative organizers. Irving said that so far, everyone is on board with the plan.

While the project has an apparent groundswell of support, some are concerned that reopening Outlet Stream could also allow invasive species into China Lake.

“I think the alewife restoration project is a good program, but it’s not a simple issue of removing dams,” said Dwayne Rioux, a registered Maine Guide and outdoor writer who lives in Winslow. “There are exotic fish species that could move upstream with the alewives.”

Nonnative species such as carp, white catfish and northern pike have been found in the lower Kennebec River, and even as far as below the Benton Falls dam on the Sebasticook, Rioux said. He doesn’t believe that there will be enough oversight to prevent an influx of exotic species if fish passageways are constructed.

Sandra Lary, a fisheries biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service, said creeping invasive species is always a concern when planning new fish passages, but said passageways are engineered to control what fish get through.

“That’s part of the planning and design process,” Lary added.

The cost of designing and building the passageways is part of the estimated $2.2 million price tag, according to Irving.

The financing picture is still coming together, and the group intends to go after substantial federal funding when it becomes available. Organizers hope to start work on dam removal this summer, but the project could take up to five years to complete, Irving estimated.

At the moment, organizers are working on a public outreach campaign that includes an alewife poster contest at the China middle school, and a series of public meetings, including a forum at 6:30 p.m., Wednesday, April 8, at the Vassalboro Grange.

Although central Maine has been exposed to alewives for years now and the glamour of expanding the population may have worn off, a project of this scale is a huge undertaking compared to efforts in other parts of the country, said Landis Hudson, director of Maine Rivers.

“Alewife restoration work is something that is maybe a little taken for granted locally” Hudson said, “but it is almost unheard of across the East Coast.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story