James Bond needs someone to put him in his place. And time.

Given the way he pops up in theaters as a fresh face every few years, it’s hard for some of us to think of the suave, unstoppable 007 as a relic. Truth is, Ian Fleming brought him to life way back in 1953, the year Queen Elizabeth II was coronated.

The books show their age. No modern reader can pick up a Bond novel without being stopped cold by some racial stereotyping that seems condescending and cringeworthy if you want to be charitable, downright horrific if you want to be honest.

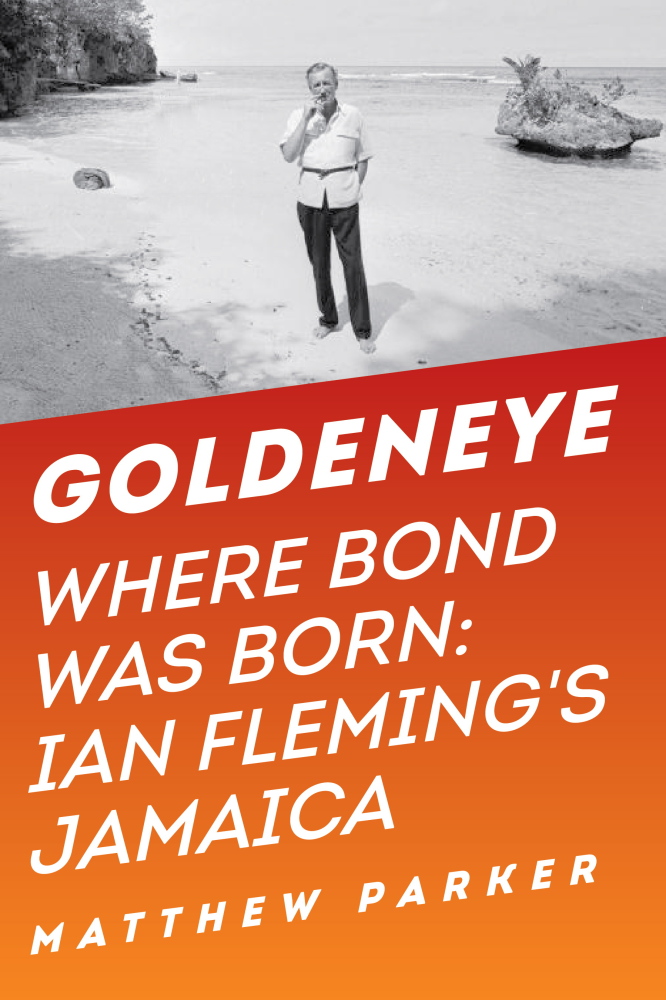

But Bond fans need feel no shame in picking up “Goldeneye.” This is no guilty pleasure. It’s a straight-up delight of a biographical narrative that crisply illuminates Bond, Fleming and the era when the sun was setting on the British Empire and dawning on the jet age.

This is not a full-scale biography. Fleming’s entire life before 1949 is quickly summarized in the opening pages, although we learn the essential facts: He was a child of privilege in a family of connections (when Fleming’s father died in World War I, his friend Winston Churchill wrote the obituary). Young Fleming, like his fictional alter ego, was irresistible to women, “notorious for his open-minded approach to sex, his obsessional interest in it and his direct manner of seduction.”

Author Matthew Parker quickly jets us from dreary England. During World War II, after attending a naval conference, Fleming vowed to a friend, “When we have won this blasted war, I am going to live in Jamaica. Just live in Jamaica, lap it up, and swim in the sea and write books.”

He kept his word. In 1946 Fleming built a stark, modern house, along “a tranquil aquamarine bay protected by a broad and tangled reef.” He called it Goldeneye, after a wartime operation he had planned for the defense of Gibraltar. Fleming, who worked as foreign news manager for the Sunday Times and apparently had a lot more pull with his superiors than the people writing and editing this review, worked a deal that allowed him to spend two months’ paid leave on the island each year.

Jamaica soon became a destination for “the new jet-set, classless, always abroad, detached from where they are, feeding their appetites.” Noel Coward rented Fleming’s home and later became a neighbor and friend; Truman Capote wrote there; and Graham Greene stayed and sparked a row involving whiskey and bedding. Names of Hollywood stars are sprinkled throughout the text.

Fleming used Goldeneye for all kinds of recreational activities: snorkeling, spearfishing, the affair with his married lover and future wife, Ann. Their passionate and tempestuous relationship is related in soap-opera-worthy detail. Like Bond, Fleming had commitment issues, and Coward found him to be “excellent source material” for his plays.

Parker balances his reporting on such upper-class decadence with details on the island’s history and politics, including its drive to gain independence and shed the plantationlike attitudes that Fleming and other white Britons would have been perfectly happy to continue. If some of these sections are the least snappy of the book, they provide necessary context and ballast. And the revelations about Bond are never far away.

He owes an awful lot to Jamaica. The spy’s name came from the ornithologist who wrote a guidebook on the shelf at Goldeneye. Fleming spent hours “floating, observing or hunting” on his reef: “For Fleming, being out in the bay was the perfect combination of action and sensuality that would become James Bond.”

Fleming’s life unfolds in stories about each Bond book, and Parker helps us find clues to the sad reality behind the fiction. Fleming’s marriage and health were bottoming out just as Bond’s popularity was becoming stratospheric (helped by an endorsement from none other than President John F. Kennedy). His 1962 story Octopussy “is really about alcoholism,” Parker tells us.

“I’ve always had one foot not wanting to leave the cradle, and the other in a hurry to get to the grave, which has made for an uncomfortable existence,” Fleming wrote privately. Like Bond, Fleming could not let go of his smoking and drinking. He died in 1964, at 56.

Bond lives. Should he? Parker’s study is good enough to explain why he endures and honest enough to make clear just how rooted he is in the past. On those racial issues, for example, Parker notes that Fleming and Bond share a distinctly colonial attitude toward black Jamaicans. Fleming’s shameful racist clichés are called out, but Parker also notes that “Fleming – and Bond – looked down on pretty much everyone who was not British and perceived people of all colours in terms of negative stereotypes of race and nationality.” By this standard, Parker argues, Fleming seems to show more affection toward black Jamaicans and Americans than almost any non-British characters.

It’s not exactly a redemptive analysis, but that’s not what this book is trying to do. Parker is out to explain an era, a writer and a remarkable character. Mission accomplished.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story