MOUNTAIN VIEW, Calif. — When Galileo viewed Jupiter through his telescope in 1610, he saw four dim objects near it that he assumed were stars. Repeated observations revealed that these “stars” orbited Jupiter like our own moon circles Earth. Thus began over 400 years of observations of Jupiter’s moons, which now number 67. But if experts who gathered Wednesday at NASA’s Ames Research Center are successful, by midcentury we may see one of these moons in a whole new light.

More than 200 astronomers, physicists and astrobiologists from around the world debated how future missions to this moon, Europa, could search for signs of life. Their discussions were jovial and academic but also imbued with a sense of urgency as the space agency plans an upcoming mission to the white and rust-colored world. This icy moon had long been a candidate for extraterrestrial life.

But in December 2012, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope detected a probable plume of water and ice erupting more than 120 miles above the surface near Europa’s south pole, raising speculation the moon may harbor a subterranean ocean that occasionally erupts to the surface. NASA officials are actively discussing additions to their spacecraft, the Europa Clipper, to investigate Europa’s life-bearing abilities.

“We are going to do a Europa mission,” said NASA Associate Administrator John Grunsfeld. “It’s too good of a chance to miss.”

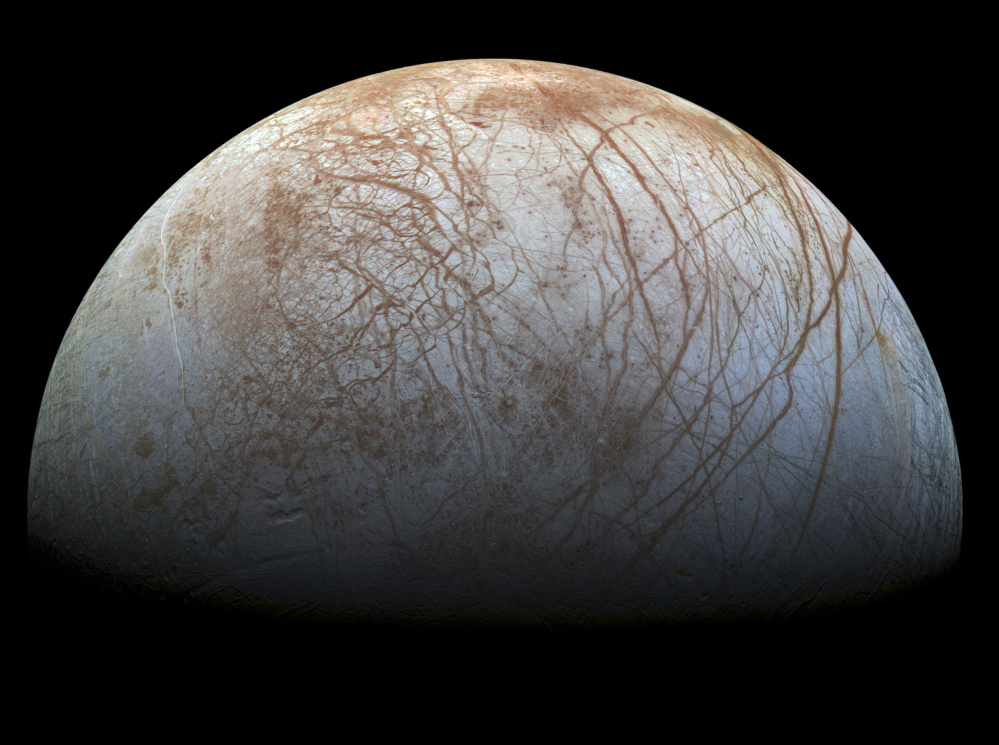

Europa is only a little bit smaller than Earth’s moon, but the similarities end there. It has a surface of ice and minerals, crisscrossed by dark streaks of material that scientists still do not fully understand. Beneath, many scientists believe frigid Europa harbors an ocean of water of unknown acidity or salinity. Deep in these seas, protected from harsh radiation on the surface, astronomers and biologists wonder if life could have evolved in its depths.

NASA intends to launch the Europa Clipper spacecraft around 2022, which could take over seven years to reach Jupiter. The mission, currently budgeted at $2.1 billion, would include repeated flybys of Europa to map the surface, learn more about its composition and study its interior, according to Dave Senske of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. Wednesday’s discussions covered how the spacecraft’s design could be modified to try to detect plume activity, sample a plume or search for signs of life on the distant world.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story