The surging buying power of the U.S. dollar has allowed consumers to benefit from cheaper imports and bargain-priced vacations abroad, but Maine’s manufacturers must now struggle to compete in a new global marketplace in which their products have suddenly become more costly.

“The rising dollar is a real threat,” said Kathie Leonard, the CEO of Auburn Manufacturing Inc., whose 50 employees in Auburn and Mechanic Falls make heat-resistant textiles. “It hurts us. I don’t know the extent it will be. I am scared to death, to tell you the truth.”

Maine-made products sold in Canada, for example, cost Canadians about 25 percent more now than a year ago. The dollar’s value has surged against all of America’s trading partners – up more than 16 percent against the Federal Reserve’s trade-weighted index of 26 other currencies.

The dollar hasn’t behaved like this for decades, except briefly in 2008 following the collapse of Lehman Bros. Holdings Inc., an event that triggered the start of a global financial crisis.

The strong dollar hurts the bottom line of small manufacturers in Maine but also giant U.S. exporters., like Procter & Gamble, the world’s biggest consumer products maker, which last month blamed the currency market for a 31 percent drop in second-quarter profits.

Generally, a rising dollar boosts importers and hurts manufacturers, although some companies have found ways to cushion themselves somewhat from the impact.

In some cases, plummeting foreign sales are offset by increased domestic sales because of the thriving U.S. economy. While some manufacturers are seeing their foreign sales tumble because their products are being priced out of the market, others are deciding to keep their prices steady and lower their margins so they don’t lose their customers. Larger companies, such as Idexx Laboratories in Westbrook, lower the risk of currency swings by using financial instruments, such as buying currency futures.

Canada is by far Maine’s largest trading partner. Many natural resource-based companies, such as those in forest products, seafood and agriculture, maintain operations in both Maine and Canada. The ability to shift the flow of commodities and production across the border can buffer a company’s currency swings.

INTERTWINED ECONOMIES

The economies of Maine and the neighboring Canadian provinces are so intertwined that a large shift in the value between the U.S. dollar and the Canadian dollar, or loonie, doesn’t have as big an impact as people assume, said Jeffrey Bennett, director of the Canada desk at the Maine International Trade Center.

“We are so dependent on each other that it sort of mitigates the fluctuations in currency,” he said.

The value of the U.S. dollar and the loonie were roughly on par until last July, when the dollar began its climb. On Friday, one U.S. dollar was worth $1.25 Canadian.

The loonie’s decline also affects the movement of people across the border. Maine draws 4 million to 5 million Canadian visitors a year.

PRICIER FOR CANADIANS

A stronger dollars means that Maine restaurants, hotels and goods are pricier for Canadians. Unless the loonie rebounds, the Bangor Mall, L.L. Bean and the outlet stores in Kittery, popular shopping destinations for Canadians, will see fewer Canadian shoppers this year. Businesses in Old Orchard Beach are particularly vulnerable because Canadians make up half of the town’s tourist population during some weeks in the summer.

It’s still too early to assess the potential for damage, but businesses are concerned and are watching the exchange rates closely, said James Harmon, executive director of the Old Orchard Beach Chamber of Commerce.

The dollar appears especially strong compared with its Eurozone competitor, the euro, which last month dropped to an 11-year low of $1.12 and on Friday was worth $1.14

The dollar has jumped in value relative to currencies around the globe, including the Japanese yen, Chinese yuan, British pound and Norwegian krone.

Countries that are major oil exporters, such as Russia and Norway, have seen the biggest declines in the value of their currency. Norway’s currency lost more than 20 percent of its value against the dollar in the past year.

The dollar’s value has increased because the U.S. economy is performing better than the rest of the world. The dollar has become a safe haven for investors as other nations prop up their weak economies by cutting interest rates and expanding stimulus programs, said Andrew Labelle, an international economist at TD Bank in Toronto.

He said the dollar will continue to increase in value in 2015, although most of its growth has already occurred.

SURGING DOLLAR AND EXPORTS

For exporters, the surging dollar makes it harder to compete on price. Rob Fuller, CEO at Harbor Technologies in Brunswick, which manufactures composite pilings and bridge beams, said the company has lowered production costs in Maine so much that its products are comparable in price with conventional products, such as traditional wood pilings. But the efficiencies are wiped out when a customer’s local currency drops in value, he said.

His said he recently submitted a bid to sell composite pilings for a project in Norway but he worries that the higher cost of the pilings due to the exchange rate will knock out his bid.

Fortunately, his company is enjoying strong sales growth in United Sates, offsetting its slump overseas.

“You look for growth from the international market and stability in the North American market,” he said.

For Idexx Laboratories, a global company that focuses on diagnostic and information technology for pet health care, stability is achieved by buying currency futures, which are contracts to exchange one currency for another at a specified date in the future at an agreed-upon price. So if the dollar strengthens in value, the contracts will mitigate the impact.

Currency futures give a company a level of predictability that is prized by investors, said Ed Garber, director of investor relations for Idexx.

In 2014, roughly 57 percent of the company’s revenue came from the sales in the U.S., and 43 percent came from international offices.

The company operates diagnostic laboratories in several other countries. The impact of the stronger dollar for those operations is not as significant because the staff is paid in local currency, Garber said. But more than a quarter of the company’s revenues is generated by products made in the U.S. and sold abroad in local currencies. For that business, the dollar’s rise has cut into the margins.

“That’s where we have the largest exposure,” he said. “Our costs remain the same, but our revenues go down.”

Large companies buy and sell a variety of currencies all the time to mitigate the impact of currency swings, said Neal Prescott, manufacturing consultant and president of the Maine Manufacturers Association.

SMALL MANUFACTURERS’ STRUGGLE

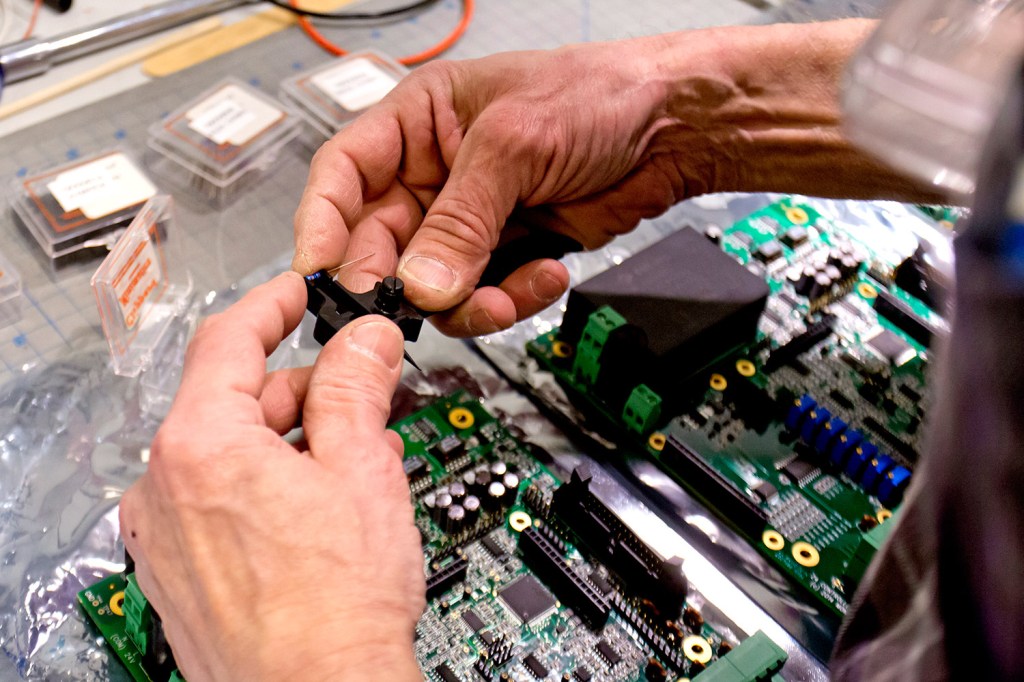

Small manufacturers, particularly those that sell a natural resource-based product, are going to struggle the most because of the strong dollar, he said.

“For most small companies, trying to export just got a lot harder,” he said.

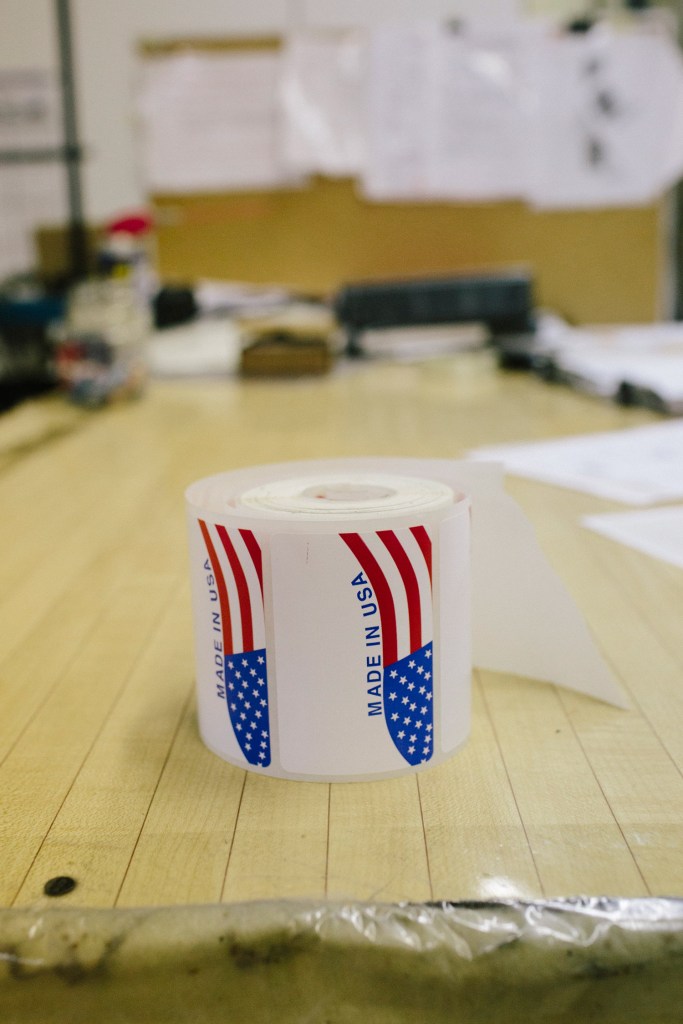

But not all suffer. For manufacturers who buy components and raw materials from other countries and build products here for the U.S. market, the strong dollar lowers their cost of production. That’s the case with Jotul North America, which obtains cast iron from a foundry in Norway and builds wood and gas stoves in Gorham.

The company in the past has imported about half of stoves from Norway, but over the next few weeks it will begin manufacturing all its stoves in its Gorham plant.

The lower cost of its imported cast iron allows Jotul to lower its prices for some models in the U.S., said Bret Watson, the company’s president and CEO.

Watson said sales in Canada are down 6 percent because the strong dollar has made the stoves more expensive there. Still most of the company’s sales are in the United States, and those sales are up 15 percent, he said, so the company overall is preforming well.

Located next door to Jotul in the Gorham industrial park is another manufacturer, the Montalvo Corp., which makes web tension control products used by manufacturers around the world and has offices in Denmark, Germany and China.

RELATIONSHIPS MATTER

Ed Montalvo, the company’s co-managing director, said his customers abroad may see some price adjustments in select markets because of their weaker local currencies, but he is reluctant to raise prices across the board because he wants to maintain his relationship with customers.

In the long term, those relationships are more important to his company’s success, and eventually the currency markets will return to normal, he said.

“At this stage of the game, we are planning to weather it,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story