Maine’s scallop fishermen are benefiting from a new management system that has made scallops more plentiful along the ocean bottom off Maine’s coast, particularly in the rich scallop beds Down East.

Despite the good news, fishermen still struggle to win a premium price for their scallops in the global marketplace. They compete in a market dominated by a large-scale commercial scallop fishery centered in New Bedford, Massachusetts, which controls more than 90 percent of the market and supplies scallops that have been caught by draggers and packed in ice for days. Maine fishermen, conversely, retrofit their offseason lobster boats and drag for scallops on day trips, providing significantly fresher scallops.

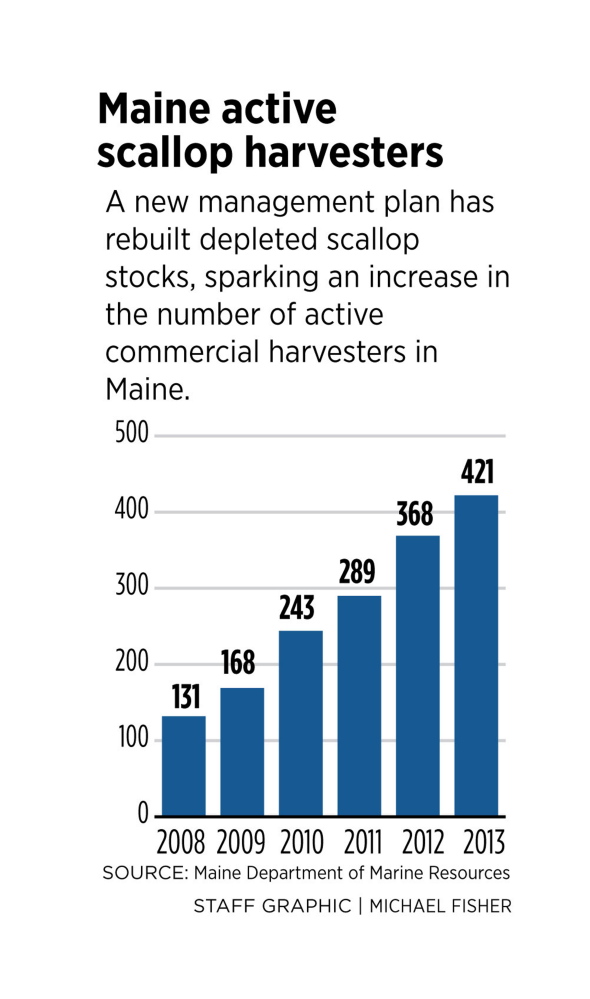

An aggressive new regulatory plan in Maine – modeled in part on the successful efforts to revive the once-depleted fishery in federal waters more than a decade ago – seems to be the reason for the increase in scallops in the state’s waters and a threefold increase in the number of active scallop fishermen, who now number 420.

The measures, which began in 2008, included shortening the season by half, imposing daily catch limits, instituting closures and mandating harvest reports. Scallop managers have a huge advantage over the managers of other troubled fisheries, like cod and shrimp: Adult scallops sit on one place, like crops in a field. And just as farmers rotate their crops, fishery managers began rotating scallop beds to give young scallops two years to grow and reproduce before being harvested.

Many Maine fishermen bitterly opposed the measures because they didn’t believe they would work and feared they would lose money. But the plan’s success has made believers out of some of its harshest critics.

One former skeptic, Mike Murphy Jr., 34, head selectman in Machiasport and a scallop fisherman, says he has seen for himself that it’s working.

In 2008, he would drag for scallops all day in Machias Bay before he could a fill a 5-gallon bucket, he says.

“Now we can fill our three buckets in a matter of two hours,” he says. “We expected this to last a month. But we are still going – no problem. We see a lot of boats, and it seems to be holding up really well.”

ROTATIONAL SYSTEM

The current fishing season is the first in which the rotational management system is being fully implemented Down East, with two-thirds of state waters now closed to fishing and one-third open. The open areas had been closed for two years.

The success of the measures can be seen in the numbers.

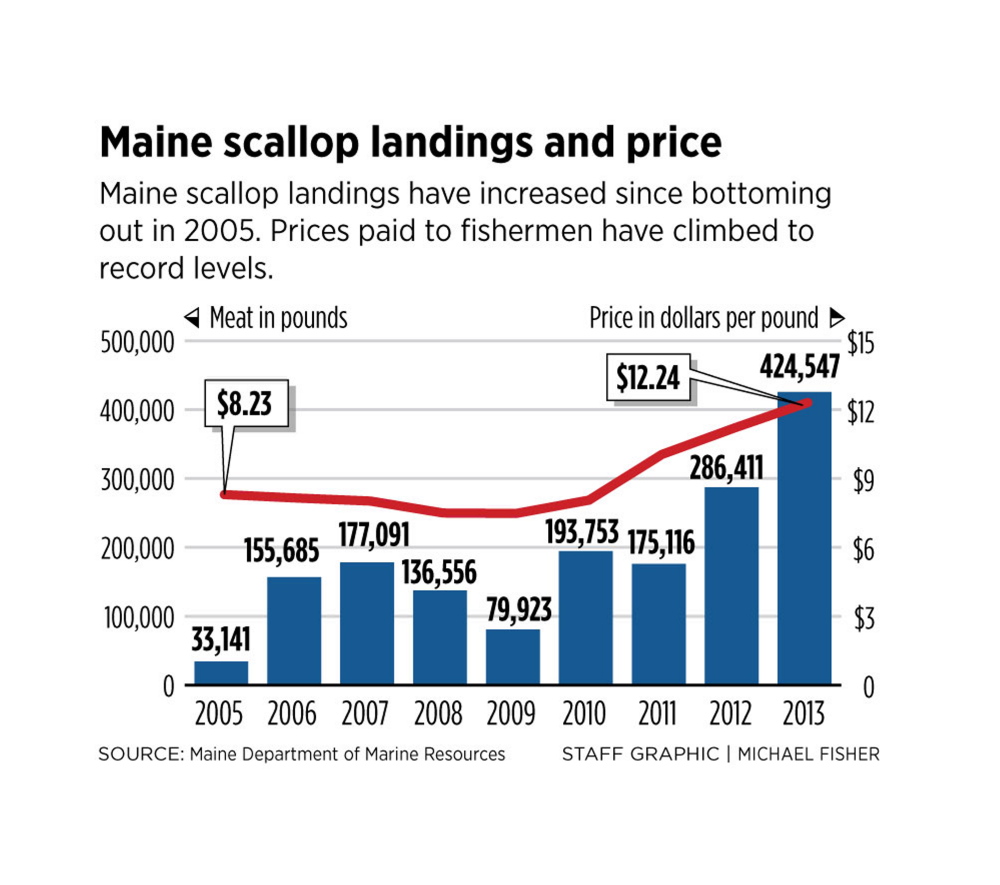

Scallop landings bottomed out in 2005, when 33,000 pounds of scallop meat were reported landed. It was the worst year since landings data were first tracked in 1950. Many frustrated harvesters had stopped fishing for scallops altogether.

So far, the resource has held up to the increased fishing pressure, although managers have shut down some areas to prevent a repeat of stock collapse. The most recent data available, from 2013, show that 425,000 pounds of meat were landed – a thirteenfold increase from 2005.

The value of scallops also is up, from an average of $8.23 per pound in 2005 to $12.24 per pound in 2013. This year, prices are at a record high, ranging from $12.50 to $14 per pound, depending on the size and the region of the state.

The rebound of scallop stocks and prices has spurred licensed scallop fishermen on the sidelines to gear up their boats to fish for scallops again. The approximately 420 active commercial scallop harvesters fishing in Maine waters this season represent a threefold increase over the 131 scallop fishermen seven years ago.

The resource this year is holding up especially well in Down East waters, such as Cobscook Bay in Washington County, says Trisha Cheney, who oversees scallop management for the Maine Department of Marine Resources.

Cheney, who attended a Jan. 22 meeting with fishermen in Ellsworth, says she heard for the first time from fishermen who were enthusiastic about their catches.

“Overwhelmingly, we are at a point in the fishery where people are still getting their daily limits and catching scallops relatively easily, although it’s taken them a little longer,” she says. “We have never seen the fishery sustained into the season this long at this rate for a number of years.”

The scallop fishery in Maine takes place in winter so draggers won’t interfere with lobster traps that blanket the bottom of the coast of Maine from late spring through fall. Most of the scallop fishermen are lobstermen who otherwise would have no other income in the winter, so the fishery’s revival is a boon to many fishing families, particularly in Washington and Hancock counties, where the scallop fishery is the strongest, Murphy says.

In addition to the draggers, there are 33 active divers who use scuba gear while gathering scallops by hand. They are governed by the same system. Maine is the only state with a significant diver fishery, although divers harvest less than 10 percent of the Maine catch.

Divers and draggers often clash, but both have benefited from the new rules, says Andy Mays, a diver from Southwest Harbor who serves on the Scallop Advisory Council, an industry group that worked with the Maine Department of Marine Resources to develop the new rules.

He says harvesters now see for themselves how the scallop population grows exponentially when left alone. “People are seeing the benefits,” he says. “They’re saying, ‘Holy cow, instead of crushing these scallops and harvesting them undersized, now we are getting beautiful product that has been able to spawn two more times and add to the increase of the population.'”

NICHE WORK

While Maine’s scallop fishery is growing, it’s still tiny. Maine scallop fishermen earned $5.2 million in 2013. That’s just a little over 1 percent of the $467 million worth of scallops landed in the United States, mostly in New Bedford, the nation’s leading fishing port by value.

The larger scallop boats that work out of New Bedford typically go out to sea for six to eight days at a time before returning with their catch, which is packed in mesh bags that are encased in ice. Processors often soak the scallop meats in sodium tripolyphosphate, a preservative that is widely used in the food industry. Soaking also makes the scallops heavier, increasing the value of the harvest.

Conversely, crews on Maine draggers toss the meat into 5-gallon buckets after shucking the scallops minutes after dragging them onto the boats. Maine boats are limited to catching only three bucketloads of scallops a day, and the scallops are brought to shore the same day.

While the fishery in federal waters is year-round, Maine fishermen harvest scallops from Dec. 1 to April 15, so the scallops are naturally refrigerated, says Dana Temple, a Cape Elizabeth scallop broker who buys scallops both domestically and internationally.

“They shuck them into a bucket and they don’t sit very long and it’s in the middle of winter,” he says, “so it’s gold.”

Alex Todd, who grew up on Chebeague Island and now lives in Freeport, has a list of 150 customers who will call him for orders. His wife, Heidi, makes deliveries. He also sells scallops to Rosemont Market & Bakery in Portland and Yarmouth, and some Portland restaurants.

In the late 1990s when scallop prices plummeted to $4 a pound, he began selling scallops out of his truck parked on Mallett Drive in Freeport. He says people discovered the difference between fresh scallops from Casco Bay and processed scallops sold in supermarkets.

“You don’t get a cleaner, fresher and purer scallop that is straight from the ocean than the scallops you get right here in Maine,” he says.

Yet while Maine’s day-boat fleet produces a premium product, its fishermen don’t get a premium price. That’s because the relatively small amount of Maine scallops are lumped into the same supply chain as the scallops landed in New Bedford and elsewhere on the East Coast and in Canada’s Atlantic provinces.

Maine fishermen are paid a little less for a better product because of the small volumes of scallops landed in Maine and the additional transportation costs of trucking scallops to the processors and freight-forwarders in Massachusetts, says Temple, the Cape Elizabeth scallop broker.

In fact, fishermen in the eastern part of Maine get a little less money for scallops because they’re farther way.

It’s a shame that Maine scallop fishermen aren’t getting more money for their superior scallops, says Togue Brawn, a Portland scallop dealer who spearheaded the effort to revive the state’s scallop fishery while working for the Maine Department of Marine Resources.

“The day-boat fishermen are getting the raw end of the deal,” she says. “They’ve got a really good product, but the markets are set up for quantity, not quality.”

ELIMINATING THE MIDDLEMAN

Although scallops are scarcer in waters such as Casco Bay, fishermen there live closer to affluent consumers and high-end restaurants, allowing some fishermen to peddle their own scallops. Todd, the Freeport fisherman, for example, earns about $1 more per pound by eliminating the middleman.

Unlike the draggers, the divers have developed a market for their scallops and get a premium price – $1.50 more per pound for smaller scallops and $3 more per pound for larger scallops, which in New York can sell for $35 to $50 a pound.

In the 1990s, Browne Trading Co., a Portland gourmet seafood purveyor, began differentiating scallops caught by Maine divers as premium “diver scallops” and marketing them to high-end restaurants in New York City.

The company has also been selling scallops harvested by Maine draggers as “day-boat” scallops, which are recognized by top chefs as being a premium product, says Nick Branchina, the company’s marketing director. Browne Trading is selling them at its store on Commercial Street at $22 per pound.

But that niche in the marketplace is too small to absorb the supply from the Maine fleet, so Maine fishermen don’t earn a premium price, he says.

“There is a gap in the supply chain,” he says.

Browne Trading maintains a clear chain of custody over its scallops, but other dealers aren’t as reputable, Brawn says. The vast majority of claims about diver scallops are bogus because there aren’t enough true diver scallops available for all those restaurants, especially in the summer when the Maine fishery is closed. As a result, most diver scallops are harvested by offshore draggers, she says.

Brawn contends there is no difference in flavor between scallops harvested by Maine divers or Maine day-boat draggers – they come from the same beds – but the marketing power of diver scallops is making it harder for the industry to create a brand for Maine scallops.

“It’s the ‘Maine’ that’s important, not the means of harvest,” she says. “Perpetuating the whole ‘diver scallop’ craze does a real disservice to Maine’s scallop industry.”

Brawn has been trying to establish a brand for Maine scallops since leaving her state job in 2011. She started a Portland company, Maine Dayboat Scallops, that sells Maine scallops directly to consumers. She travels to New York City several times a year, going to public markets and corporate events to cook up Maine scallops on a portable burner, offer samples and take orders.

About a week ago, she gave away 25 pounds of samples at an event at Google’s office in Manhattan and collected 80 email addresses. She also delivered about 80 pounds to other city customers who had made orders. She charges between $26 and $30 a pound.

The best way to sell people on the concept of a Maine scallop is to let them try it, she says.

“You need to taste it to comprehend it’s on a different point of existence,” she says.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story