The first time I heard about Sean Thackrey, several years ago, someone told me he was a California winemaker who refuted the notion of “terroir,” that sense of place arising from a nexus of soil, climate and culture. I was young and in the theoretical throes of “terroirism” (still am, kinda), so I paid Thackrey little mind.

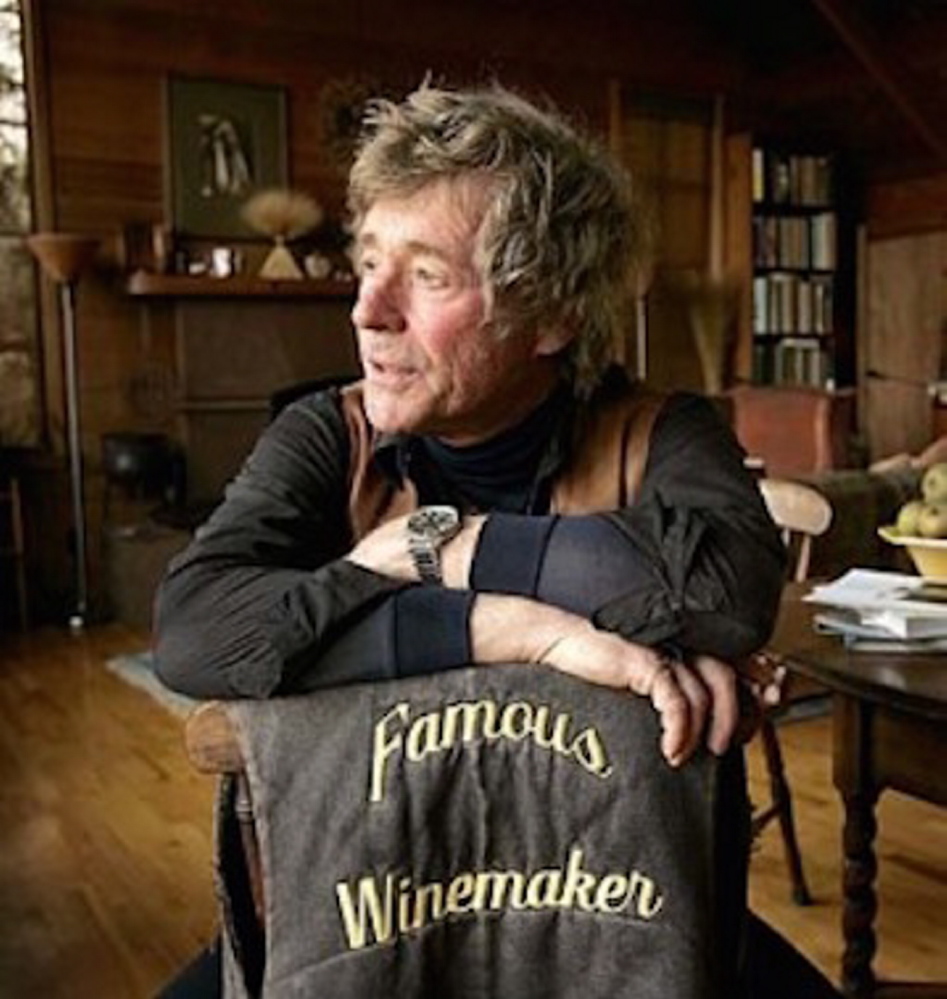

Then I heard that his website was wine-maker.net, another thumb in the eye of those who would place land and lineage above people and process. Eventually someone I respect handed me a bottle of Thackrey’s Pleiades Cuvée XXII, with a challenge. “Here ya go, Mr. Soul of Wine,” my friend said, referring to my email and blog address. “You think you know about soul? This wine is soul. Bow down, and learn.”

I adored – adore – that wine, along with the latest cuvée, XXIII. As much as I loved the Pleiades and the other wines from Thackrey I have tasted, however, I wasn’t yet sure I could agree with my friend’s assertion. Thackrey’s wines complicate the very notion of what “soul” in wine is; they call into question whether wine can even have it.

Thackrey wines seem to have a psychological, rather than geological, foundation. The mode is of shift more than stability.

Flirtatious one moment and luxurious the next, as polished and clear as a bell at first note but then with a lingering fuzziness like a Marshall amp, the wines are furiously inventive in their ability to inhabit simultaneously more than one point in space and time. You sense a wild-haired conductor on the podium, consciously unhinged, his baton accurate but hard to follow. Wines like this don’t just happen. And so Thackrey is – must be – correct: Wines do not descend to us by grace of the Terroir Gods. They are made.

By calling himself a winemaker, Thackrey, who ran a successful art gallery in San Francisco before he started making wine in Bolinas in 1980, is not suggesting that wine is a sterile, mechanized, tyrannical relationship of human to grapes. Rather, he is trying put the entire picture into focus. A quantum scientist might call this bringing the observer into the field of cognizance. Grapes, tools, hands, consciousness: all various elements of one cohesive endeavor.

“I regard humans as being part of the natural landscape,” he told me. “You can’t get around the human part of it. That’s my whole project. The dehumanization of wine is what I don’t like. The number of viticultural decisions that have to be made is enormous, so why talk about the geology but not the viticulturist?”

For Thackrey, the question isn’t rhetorical. His hypothesis is that the modern notion of “terroir,” most fully developed under the French appellation system, is a sort of “viticultural racism” that preserves social hierarchies and class distinctions, and disguises an elaborate marketing scheme.

“If people just said, ‘Vineyard characteristics are an important part of a wine,’ I’d be happier,” he said. “But, overall, it’s like cooking. A good cook looks at the material in front of her and goes from there. She doesn’t follow a particular process because of pre-existing rules for chicken or salmon. She makes choices, just as I do.”

The choices Thackrey makes are interesting but hard-won and empirical, and they express a uniquely dynamic relationship between tradition and experimentation. “Tradition is the fossil form of innovation,” he said.

He, more than just about any other winemaker alive, should know. That’s because Thackrey happens to be a curator of historical texts about winemaking. His collection includes original fragments from ancient Greece, ancient Rome and the medieval era, up through lengthy documents from the 16th through 19th centuries.

He has translated and digitally scanned many of these, and provides the documents free of charge at his website. Also included are pithy introductory notes: “Dr. Jules Guyot explains why the French are better than everybody, and offers serving suggestions.” Or, about Jean Pascal: “Fermentation as the explanation for everything, including – finally! – sex.” From Rome, a “tantalizing fragment of a long-destroyed civilization: the winemaking instructions of Mago the Carthaginian.”

If you thought any aspect of winemaking, from fermentation time to how to use oak, was consensually fixed long ago according to universal principles, 15 minutes at wine-maker.net will convince you otherwise, and bring you into a provocative centuries-long argument among practitioners.

Don’t think for a moment that these texts are merely historical curiosities to him. For example, almost entirely alone among contemporary winemakers anywhere, Thackrey “rests” his grapes for 24 hours after they are brought to his winery, fermenting overnight. “That existed in winemaking history for a long time,” he said, “up until Bordeaux in about 1875. I read about it and got very curious, and gave it a try. I thought the result was unambiguous. That’s the way I like to use these books: to find out what these things actually are, how they actually function.”

An ahistorical approach, Thackrey argues, is due to ignorance or laziness, not any conscious consideration of the body of knowledge that has developed over time.

Thackrey makes his wines from fruit sourced from growers in Napa Valley, Marin County and Mendocino. Most of it is organically farmed and uses “extremely little” sulfur dioxide. “I just think the wines taste better that way,” he said. “It’s that simple.” He calls his winery “a rural slum,” which utilizes outdoor open-top fermentation “because I never had any money and I had no other place to put the wines.”

The wines are complex, mercurial, sinuous. Their pleasures are immediate, but burrow deep over time, in accordance with Thackrey’s desire to make wines “that taste different every time, just like a conversation, a relationship. … I have made some wines that don’t change in that way, and I don’t release them.”

Thackrey’s Pleiades XXIII Old Vines Red ($33) is the gateway. Texturally electrified though all polish, finesse and curves, this cuvée of sangiovese, pinot noir, zinfandel, viognier and who knows what else is so pure and perfumed, your whole body softens as you drink. Red cherry and berry, a half-dozen different licorice flavors, real vanilla, baking spice, cedar and a lot more are wrapped up in a luscious umami bow.

The Sirius Marsten Vineyard Petite Sirah 2010 ($60) is a wallop of Napa fruit. Big to the point of bursting, it has all the unfiltered fuzziness, grain and dust absent from the Pleiades. Bitter chocolate, herbs and huge purple fruit animate it, a heavy-duty metal song with feedback buzzing.

Somewhere between those two poles lies Thackrey’s voluptuous white La Pleiade Lot 1 ($33). Waxy-feeling and attractively plump in the middle, the main drama of the wine lies in its texture: seriously tannic, with a dense, gritty, almost sandy touch. It softens on its second day open and expands its flavor spectrum by the minute: Golden Delicious into orange citrus and guava, white peach, milk chocolate, walnut, bitter almond. Like its red brother the Pleiades, it shines in all sorts of varied dining situations.

The more I drink these wines, the readier I am to acknowledge that there’s a soul animating all these scurrying pleasures, after all.

IN A RECENT column, I suggested that wines improve after the bottles have been open at least a day. Several readers followed up to ask whether I meant with a cork in the bottle or not. Generally, I meant with a cork in the bottle – and the bottle (red, white, whatever) in the fridge. If you’re not drinking any at first, decant and pour back into the bottle just to bring some oxygen into the picture. Very bold, tannic reds (young Napa cabernet sauvignon, Bordeaux, Italian merlot, etc.) could be left in the decanter. In the end, you should experiment to find what works best for you.

Joe Appel works at Rosemont Market. He can be reached at:

soulofwine.appel@gmail.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story