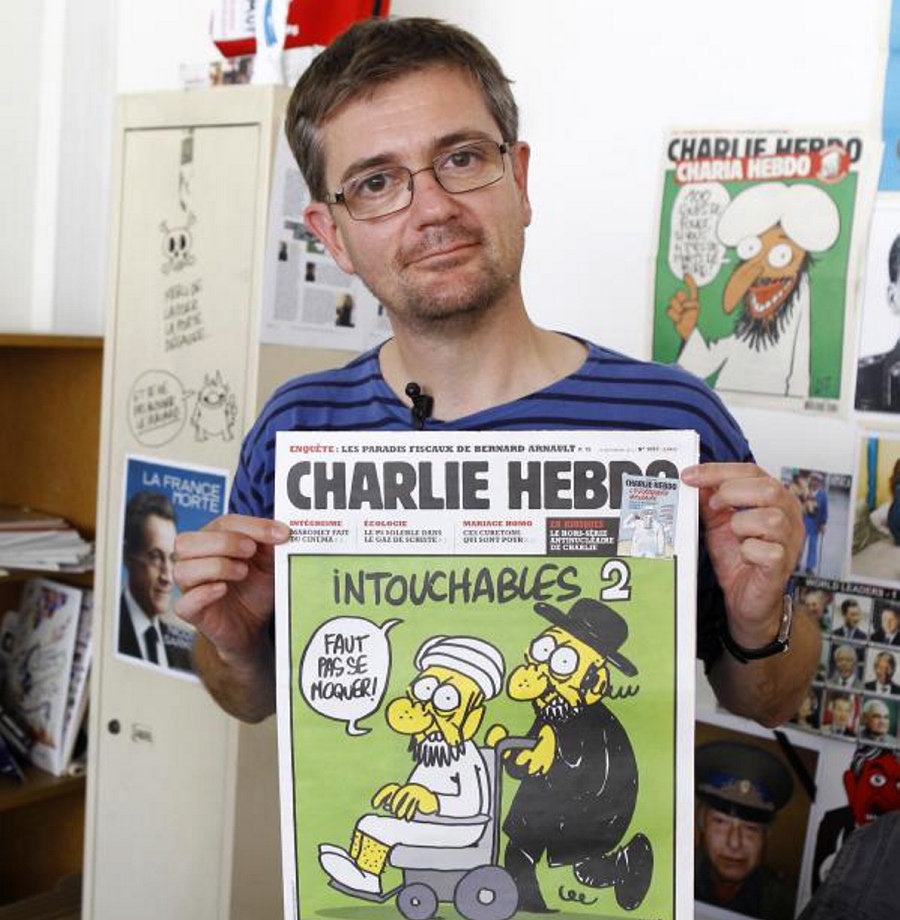

Several publishers in Western countries have disgraced themselves in recent years with self-censorship to avoid being targeted by Islamic militants. The French newspaper Charlie Hebdo did the opposite: Even after its offices were firebombed in 2011, and even after its editor was put on an al-Qaida wanted list, it continued to courageously publish cartoons and articles lampooning Islam — as well as Christianity, Judaism and established religion in general.

Consequently, the heinous attack it suffered Wednesday — when gunmen shouting “Allahu Akbar” invaded its Paris offices and slaughtered 12 people, including editor Stéphane Charbonnier and the police officers defending him — is a direct challenge to the West’s commitment to free expression. The reaction must be not only one of protest and determination to apprehend the perpetrators. Media in democratic nations must also consciously commit themselves to rejecting intimidation by Islamic extremists or any other movement that seeks to stifle free speech through violence.

That was the course Charlie Hebdo followed in 2006, after the publication of anti-Muslim cartoons by a Danish newspaper led to death threats against that paper’s editors and violent protests outside Danish embassies in Muslim countries. The French newspaper reacted by republishing the cartoons.

Several years later, a Charlie Hebdo cover announced the prophet Muhammad as a guest editor; that preceded the bombing of its offices. But Charbonnier and his fellow journalists remained undeterred: A tweeted cartoon sent out shortly before the attack facetiously offered greetings from Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

We have objected in the past to expressions that appear intended to gratuitously provoke or offend Muslims, particularly in European nations such as France, where a large Muslim population suffers from chronic discrimination and is the target of demagoguery by populist political parties. But such criticism does not justify censorship, much less violence. Charlie Hebdo, which once published a cartoon of the pope delivering Communion with a condom, did not single out Islam. More important, its persistence in the face of threats has amounted to a defense of free expression on behalf of all media — including those, like Yale University Press, that have practiced self-censorship rather than publish anti-Muslim cartoons.

In the aftermath of its worst terrorist attack in decades, France will need to re-examine its policies for protecting journalists and other vulnerable targets on its territory; the measures taken to guard Charbonnier proved inadequate. The threat the country faces from Islamic extremists is likely to get worse: Hundreds of its citizens have traveled to Syria to fight for the Islamic State. President Francois Hollande, who said that other terrorist attacks inside France had been foiled recently, appropriately raised the country’s alert status to its highest level.

Equally important is that media across the West refuse to be cowed by violence. The attack in Paris comes after a year in which two U.S. journalists who traveled to Syria were beheaded by the Islamic State and theaters across the country refused to screen a movie lampooning North Korea because of the threat of violence. Such acts cannot be allowed to inspire more self-censorship — or restrict robust coverage and criticism of Islamic extremism.

Editorial by The Washington Post

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story