Pain is all in your head. But that doesn’t mean it’s not real.

We feel pain because our brains tell us to. Sometimes it’s in our best interest – a warning meant to keep us from injuring ourselves further. Other times, as in the case of chronic pain, it doesn’t seem to serve a purpose at all.

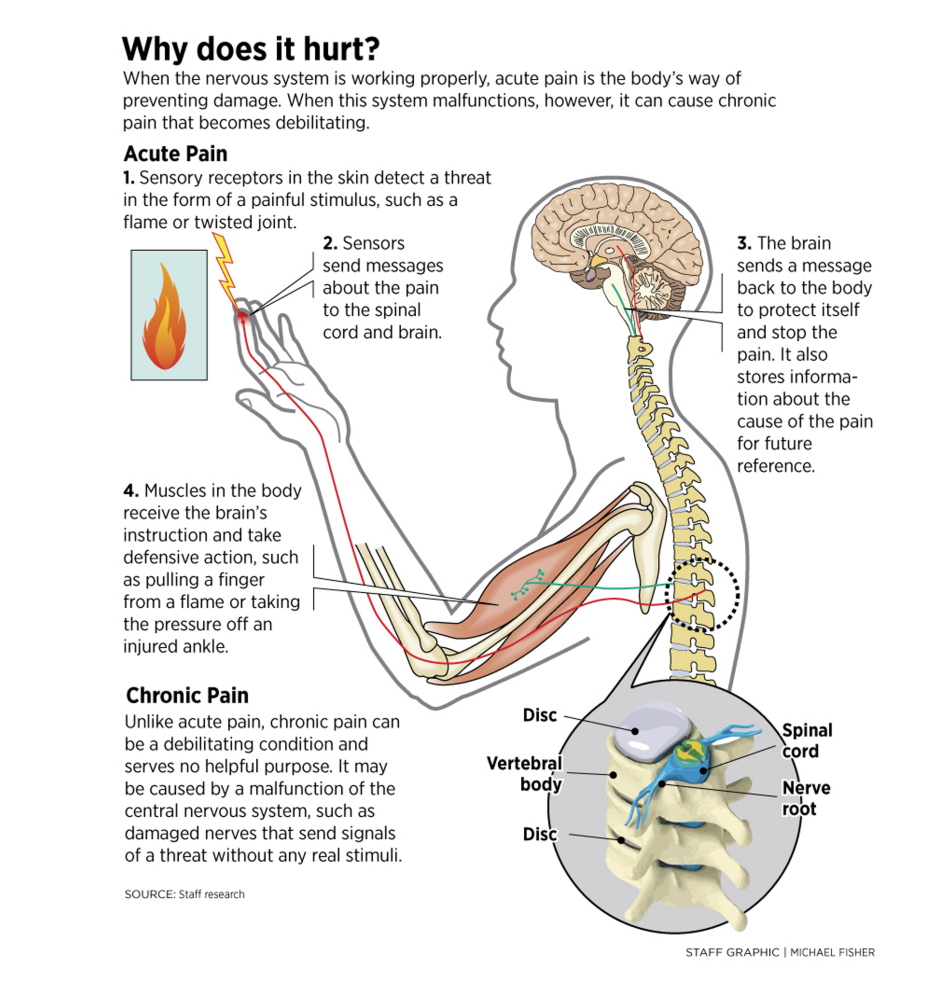

Scientists have long understood the “good” pain; acute pain, that is. Here’s how it works:

Within our tissues is a certain kind of nerve ending, or receptor, that reacts to potentially harmful things happening to our bodies.

Three types of stimuli cause that reaction, explained Dr. Stephen Hull, medical director of the Mercy Pain Center in Portland.

There are mechanical forces, like pinching from a pinprick; thermal changes, like a hand on a hot stove; and chemical stressors, which can be felt when lemon juice hits an open wound or when lactic acid builds up in your muscles from lifting weights or simply sitting too long.

The pain sensors, called nociceptors, detect those stimuli – just as other types of sensory receptors detect non-harmful stimuli, like your foot touching the ground. The sensors send messages to the spinal cord, which then alerts the brain that there’s harm.

After the brain receives the warning, it decides whether the harmful stimulus is a threat to survival and, if so, sends out its own message causing reactions throughout the body. Among them are the rush of blood to the muscles to make them move faster, the white blood cells sent to the site of the injury to start the healing process, and the sensation of pain, which tells the body to move away from the source of harm and teaches it to avoid that stimulus in the future.

Ever realize you’ve been bleeding but didn’t notice when you were cut? That’s an instance where the brain decided the injury wasn’t a threat and didn’t send the signal for you to feel pain, said Hull.

That also might happen when a person is playing dead after being mauled by a bear, he said; the brain knows that making the person feel pain won’t be helpful for survival.

After an injury, a person will continue to feel pain while the body recovers, as a reminder not to use the wounded area so it can heal.

But sometimes a person continues to hurt after the body has healed and the pain seemingly serves no purpose. Sometimes a person feels pain with no apparent injury or underlying cause. This type of pain is something scientists know a lot less about.

Generally, when pain persists for more than six months, it’s considered chronic, said Hull.

One reason a pain might linger is as a result of damaged nerves that fire signals without a stimulus. Another theory, Hull said, is that having an overblown reaction to an injury, called catastrophizing, can contribute to acute pain becoming chronic.

What doctors do know about chronic pain is that, over time, it gets worse.

Unlike other senses that adapt to consistent stimulation, the body gets more sensitive to pain.

In his book “Understanding Pain,” Fernando Cervero, president of the International Association for the Study of Pain, offers the example of a slight rub while trying on a new shoe that becomes unbearable the longer it’s worn.

(In contrast, the rumble of a washing machine or a noxious odor in a room becomes unnoticed the more time spent around it.)

Part of the reaction to a harmful stimulus is that the pain sensors in the area create more receptors, making them react more easily to stimuli, Hull said.

When pain doesn’t go away, the area can become so sensitive that the touch of a bed sheet or a light breeze might be all it takes to make someone writhe, he said. In that case, the pain takes over the patient’s life.

Progressive pain management practices, like those used at Mercy Pain Center, include cognitive behavioral therapy by changing the thoughts and behavior associated with pain to improve the perception of it by going back to the source – the head.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story