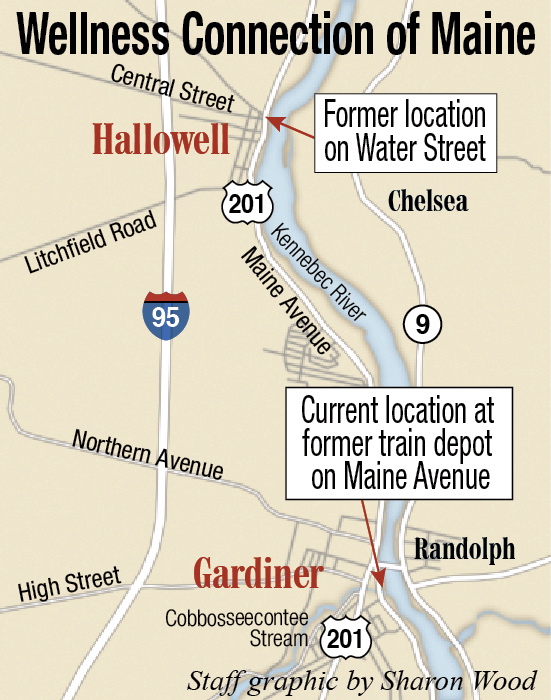

GARDINER — The former train station on Maine Avenue will open its doors next week for the 103-year-old building’s newest use — a dispensary for medical marijuana.

While some in the community opposed the Wellness Connection of Maine opening the dispensary in Gardiner, city officials were on hand at a ribbon cutting ceremony Monday morning to applaud the state’s largest medical marijuana provider’s decision to move its dispensary for the region from Hallowell to Gardiner.

“This is all about compassion,” Mayor Thomas Harnett said at the ceremony. “This is about making medical marijuana available to persons who are suffering from debilitating diseases that simply do not respond to more traditional forms of medicine. I am happy that we are able to do that in our community, and I’m confident that we have a new member of our community that we’re going to be proud of.”

The building, which was built in 1911, has been vacant since 2003, when the Boys and Girls Club of Greater Gardiner moved to the former elementary school on Pray Street.

Officials for Wellness Connection of Maine, a nonprofit organization with dispensaries also in Portland, Brewer and Thomaston, said they’re moving the dispensary to Gardiner from downtown Hallowell because they need a larger, more accessible location for their patients. The operation will not change, except for the addition of a commercial kitchen for making medical marijuana baked goods, said Patricia Rosi, CEO of Wellness Connection of Maine. Since earlier this year, the dispensary in Hallowell has been offering edibles made through a partnership with Slate’s Restaurant & Bakery in Hallowell.

Rosi said the Gardiner building, which Wellness Connection is leasing, will provide all the organization’s dispensaries with the edibles they sell going forward.

Besides the former train station being a better-suited location for its patients, Rosi said the organization, established in 2011, is pleased to be a steward of the historic building.

“We’re really proud and honored to able to bring life back to this building that has been abandoned for more than 10 years,” she said.

The project faced objections from a few residents at a Planning Board public hearing in July. Some said they wanted to see the historic building opened for a use the public could enjoy, while others objected to the proposal because of the nature of the operation.

But Harnett said he thinks part of the resistance was because medical marijuana is new.

“This is a product that we all grew up being told was illegal, and now it’s legal for certain very controlled uses,” he said. “There were concerns that people were going to be coming here and then smoking in their cars or outside, and you’ve heard that that’s not going to happen.”

Harnett said he thinks there were also concerns that by approving the project, the city would be sending mixed messages to kids about marijuana use, giving them an excuse to ask why they’re not allowed to use it too.

“The answer to that is the same reason you don’t abuse oxycodone. The same reason you don’t abuse other prescription drugs. It’s a crime to do so,” said Harnett, an assistant attorney general for the state. “I think once the newness wears off, a lot of those concerns will be allayed.”

Becky DeKeuster, founder and director of community and education at the organization, said another benefit of the Gardiner location is it will give patients more privacy when entering compared with other dispensaries. She said some patients at other dispensaries have said they avoid going at certain times so they are not seen by their neighbors shopping in the area.

In Gardiner, patients will enter in the rear of the building, on the Kennebec River side. After checking in at a receptionist’s window, the patients are allowed into the main room of the dispensary, which features brick walls and the original wood board ceiling.

Ian Jacobs, the project manager for the renovation, said the color scheme and counters of the Gardiner dispensary are similar to the others, but the Gardiner dispensary is the only one in a standalone building. The exposed brick and wood ceiling also make it unique, he said.

“As soon as I saw it, I said, ‘Wow, this is awesome. This is absolutely great,'” Jacobs said.

Ted Axelrod, a patient who uses the Portland dispensary, spoke at the ribbon cutting about the benefits of medical marijuana. Axelrod, 48, of Yarmouth, said he had been struggling for years to find the right combination of prescription drugs to treat his post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Every traditional prescription I’ve taken, which I still take, was missing a piece of the puzzle, and I was unwilling to take other things to fill in that gap,” he said.

Axelrod, who said he’s been a patient at Wellness Connection of Maine since last April, said the employees at the dispensary were helpful in finding the right marijuana strain for his symptoms. He compared the dispensaries to traditional pharmacies, saying you wouldn’t go into a pharmacy and buy something without speaking about it with a pharmacist first.

Axelrod is married to Susan Axelrod, an online content producer and staff writer for MaineToday.com and the Portland Press Herald, which is owned by MaineToday Media, which also owns the Kennebec Journal.

The state created the network of medical marijuana dispensaries in 2009 in an expansion of a previous law that also allows certified caregivers to grow the plant for a limited number of patients.

The law allows a dispensary in each of the state Department of Health and Human Services’ eight public health districts, although the department is able to expand that number after a review.

Rep. Gay Grant, D-Gardiner, also spoke at the ceremony, saying she appreciates the struggle and courage it took to start the medical marijuana industry.

Paul Koenig — 621-5663

Twitter: @paul_koenig

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story