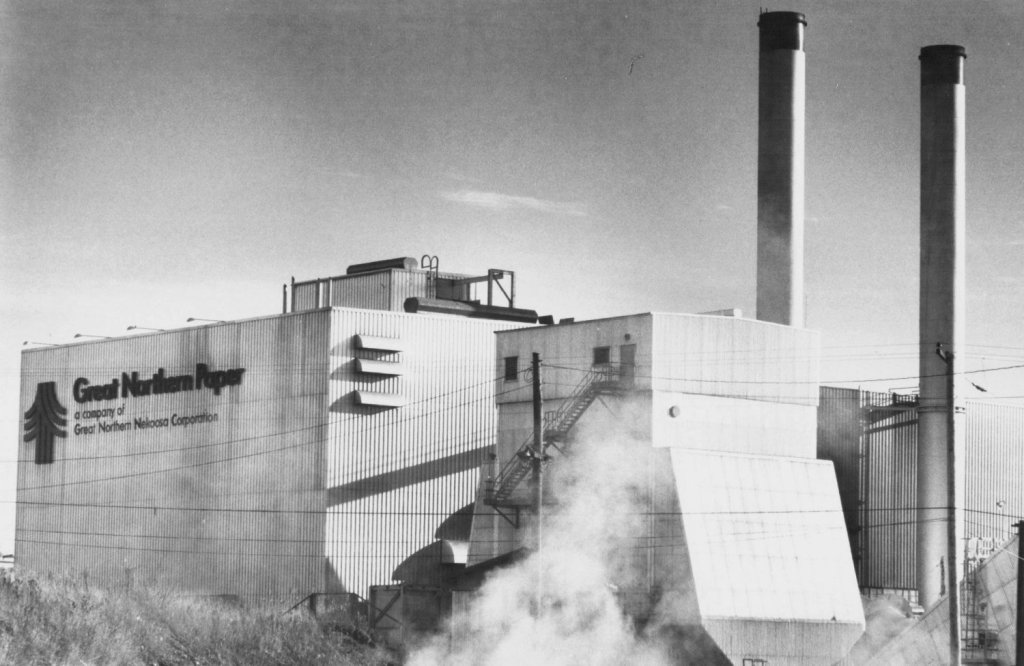

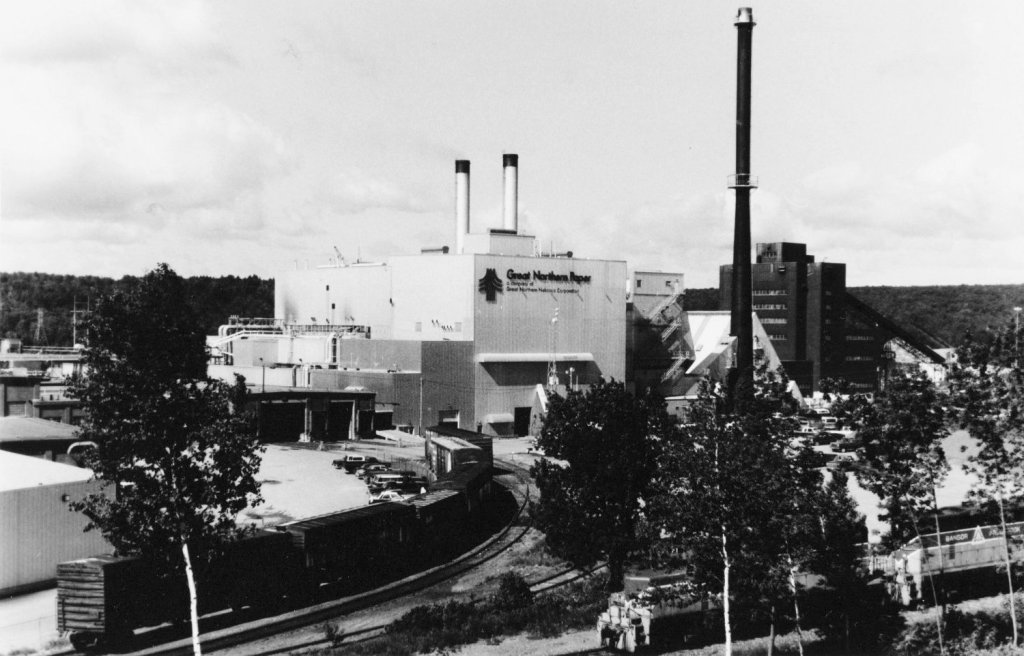

Great Northern Paper Co. in East Millinocket has filed for bankruptcy, a move that could spell the end of papermaking in what was once the heart of Maine’s paper industry and dashes local residents’ hopes for an economic turnaround.

The company filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy on Monday, which would allow it to liquidate assets to pay off creditors. It listed more than $50 million in liabilities and nearly 1,000 creditors. The filing was made at the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Wilmington, Delaware, where the company is incorporated.

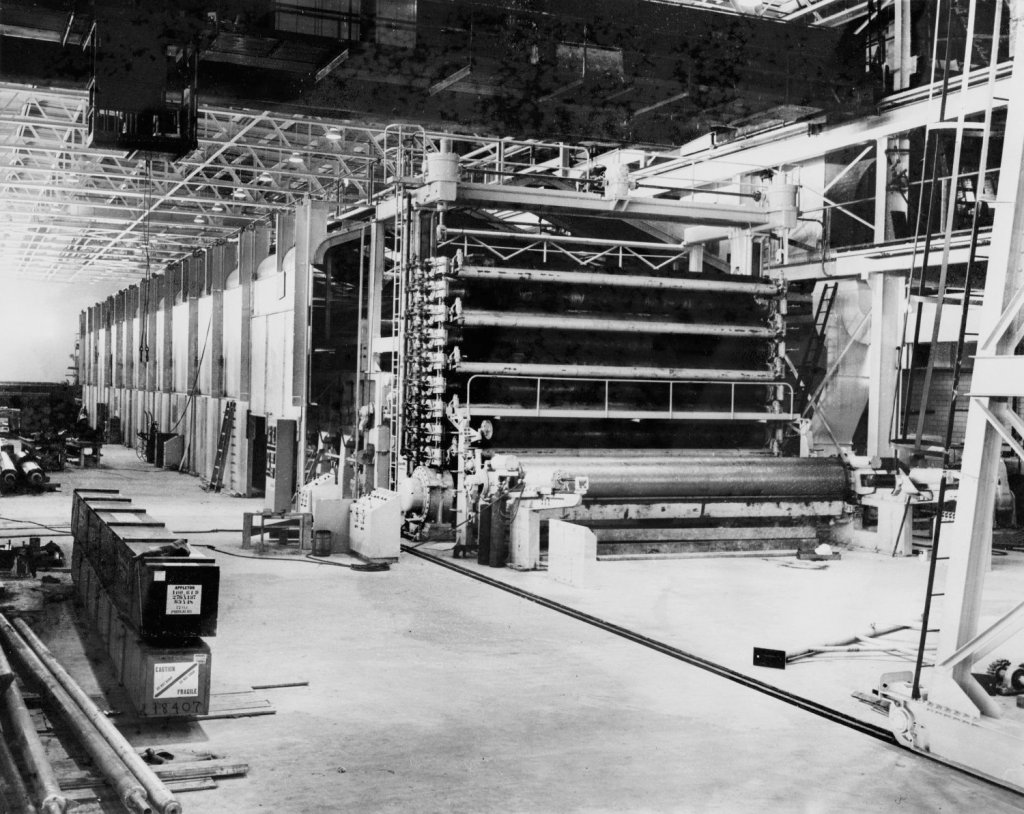

The company, which is managed by the New Hampshire-based private equity firm Cate Street Capital, shut down its East Millinocket mill in late January and laid off more than 200 workers a few weeks later, citing rising costs for energy and wood. The mill produced newsprint, including some used by the Maine Sunday Telegram, and paper for the book publishing industry, including the 2011 blockbuster “Fifty Shades of Grey.”

The bankruptcy is a blow to the community and the laid-off millworkers, who for seven months had pinned their hopes on the mill restarting. As recently as two months ago, when the Portland Press Herald was given a tour of the mill, company officials said they were still working on a plan to restart it and make paper again.

“I’m pretty sure it’s going to start up again, but there are no guarantees,” Willis Blevins, the mill’s director of operations, said July 18.

A Chapter 7 filing means the company is liquidating its holdings. A Chapter 11 filing indicates it is reorganizing in an attempt to continue doing business.

A skeleton crew has been employed in East Millinocket to work on the restart plan and keep it ready to resume operations. A sister mill in Millinocket, which has been idle since 2008, is in the process of being demolished.

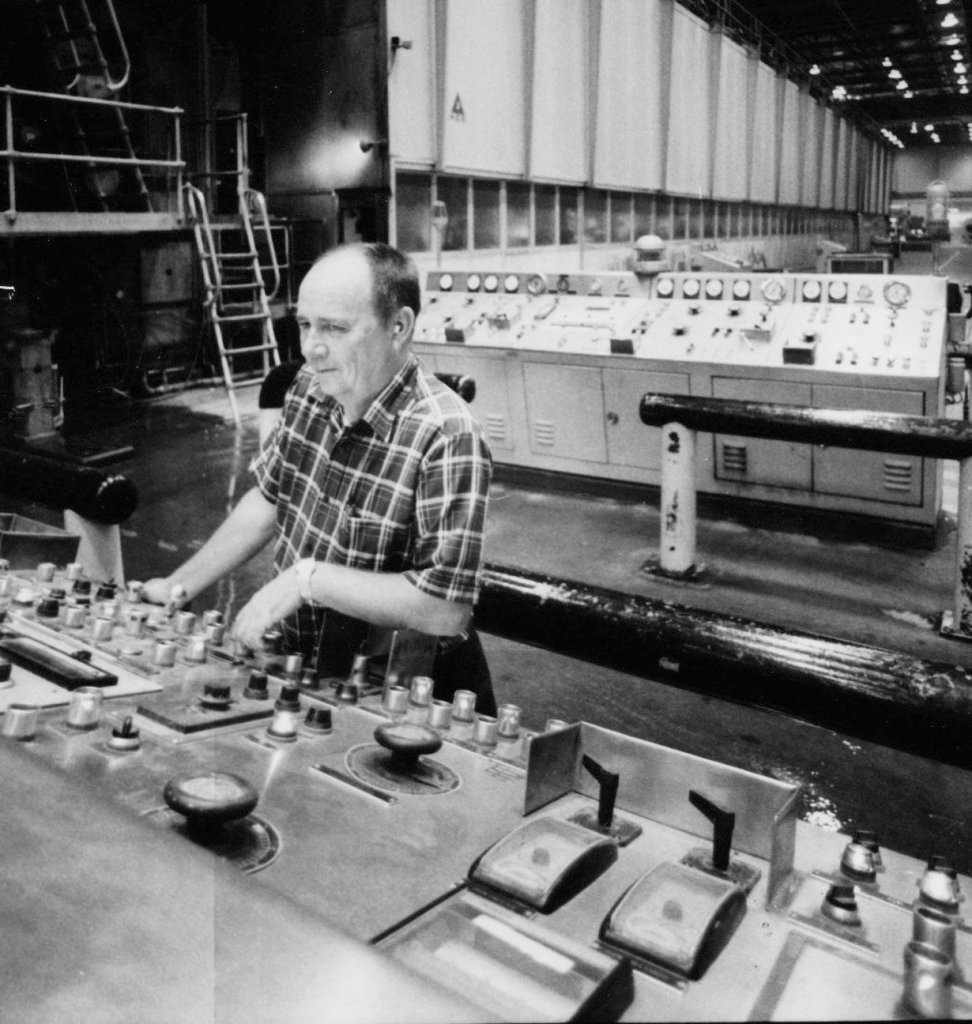

Stu Kallgren, president of the local paperworkers’ union and a member of that skeleton crew, had not received official word from the company Tuesday afternoon about the bankruptcy. He was reached by cellphone when he was on his way into work as manager of the mill’s wastewater treatment plant.

“I don’t know what’s going on,” Kallgren said. “This is as much a surprise to me as it is to anyone. … No one’s called me and told me not to come in to work.”

Kallgren had heard rumors about bankruptcy, but said he had conversations with Great Northern President Ned Dwyer about potential investors as recently as last week.

“(Dwyer) was supposed to be up here with a possible investor this weekend,” Kallgren said. “He said he was going to stop in and see me, but I never heard from him and he never came into the mill.”

Dwyer did not respond to a phone call and email seeking comment. Neither did Alexandra Ritchie, a Cate Street managing director in charge of government and community relations.

Although disappointed, Kallgren said he was not surprised that he and the union were left in the dark.

“We hear things (about) this company from the news media and rumor,” he said. “It’s unfortunate. We’re supposedly one of their biggest assets – the employees – but when it comes right down to it, we’re the last to hear anything. That kind of bothers me. I don’t think that’s right.”

Kallgren isn’t alone in being disappointed in Great Northern.

Joanna Bradeen, chief financial officer at Hartt Transportation in Bangor, which is owed more than $227,000 by Great Northern, said her company is working with its attorney to research bankruptcy procedure issues.

“I can’t tell you what I would like to say,” she said when asked about her reaction to the filing.

ANOTHER DOSE OF BAD NEWS

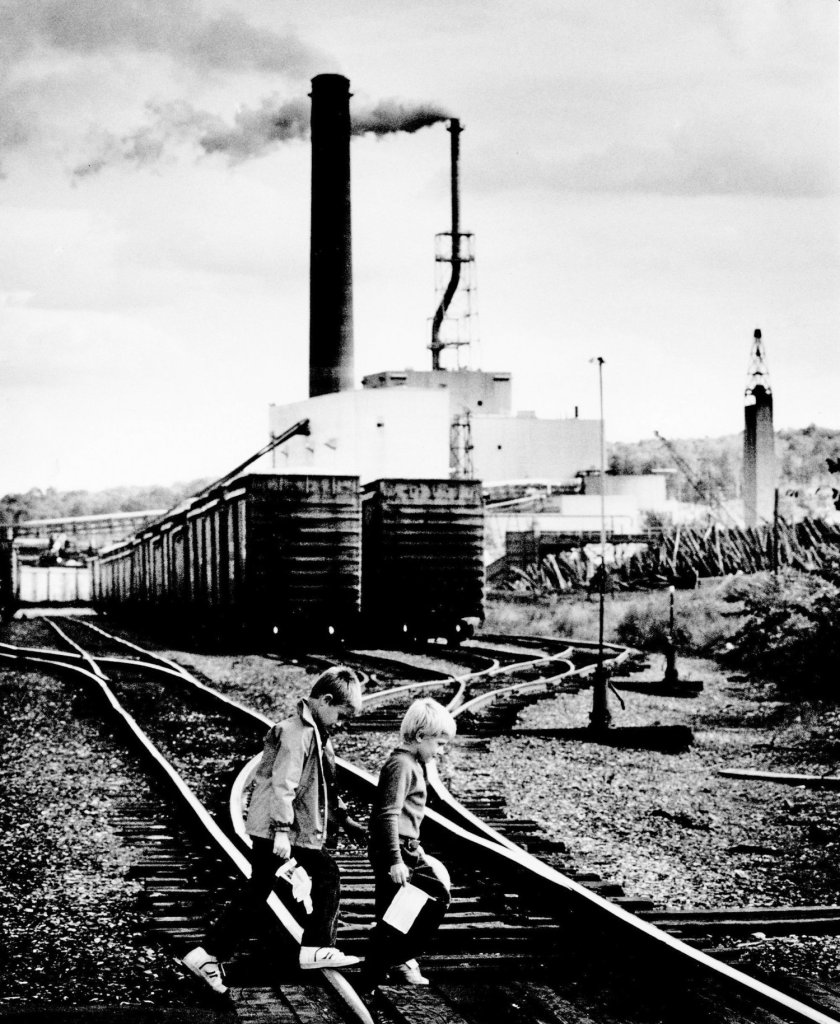

The bankruptcy filing is another blow to an area of the state that has hemorrhaged jobs and people. During its peak of paper production in the 1960s and 1970s, the original Great Northern Paper Co. employed 4,000 people at mills in Millinocket and East Millinocket and contributed to some of the state’s highest per-capita incomes. In 1973, average annual gross manufacturing wages in the Millinockets were $11,951 (roughly $64,000 in today’s dollars) compared with a state average of $7,050 (nearly $38,000 in today’s dollars), according to a Maine Department of Labor report.

But global competition eroded Maine paper company profits and caused the industry to contract.

Battered by the recession and facing a shrinking demand for paper, the mills’ previous owner, Brookfield Asset Management, closed the East Millinocket mill in 2009. By 2011, Brookfield was offering to unload both mills for $1 and set a deadline before it would start dismantling the mills built in the early 1900s and sell them for scrap.

The state interceded and took ownership of the mills, hoping it could find a buyer that would restore lost jobs and taxes. Through a series of conditions that included a pledge to modernize and restart the East Millinocket mill, the state sold the mills to Cate Street for $1 in 2011.

Since 1990, Millinocket has lost 35 percent of its population and its unemployment rate hovers around 20 percent. The town has been seizing homes by the dozens after people walked away and let them fall into disrepair. Real estate values have plummeted.

“I feel like I’m the captain of the Titanic,” Peggy Daigle, Millinocket’s town manager, told the Press Herald/Telegram in a series about the area’s economic fall and potential resurrection.

Some residents are hoping the area, part of the state’s Katahdin Woods and Waters region, will become a hub of tourism, and they look to the emergence of new conservation and recreation areas that are expected to draw tourists.

Others hold out hope that papermaking hasn’t entirely disappeared from the community.

Angela Cote, interim administrative assistant to the Board of Selectmen in East Millinocket, said residents remain hopeful that new owners will buy the mill and reopen it. Still, the news of the filing has hit this town of about 1,700 residents hard, she said.

“It’s a small community, and the mill and the paper industry mean a lot to them,” she said. “Every time someone comes and goes out, it is heart-wrenching.”

Rep. Steven Stanley, D-Medway, who worked at Great Northern Paper for 42 years, including two years when it was owned by Cate Street, said he hopes the bankruptcy will allow someone to buy the mill at a “reasonable” price and bring people back to work.

“You have to wait and see what happens and who the players are,” Stanley said.

He said there are few other options for work in the three towns he represents, East Millinocket, Millinocket and Medway. Some people are commuting to Bangor 65 miles away for jobs that pay a lot less than what they earned working in the mill.

Many families are moving away, he said.

“Here you have three little municipalities, and the biggest employer for 100 years is gone,” he said. “People are packing up and leaving.”

FUTURE OF PELLET PROJECT UNCLEAR

The bankruptcy filing calls into question whether another Cate Street Capital project – a $140 million renewable energy plant intended for Millinocket – can move forward. That project, also managed by Cate Street through Thermogen Industries, was expected to be built on the site of the former Millinocket mill and produce black pellets, called biocoal, for a growing European market.

Cate Street expected to use waste wood from the East Millinocket mill as the raw material for the pellet operation.

The Thermogen project has been plagued with its own problems. In April, it lost $9 million in state-backed financing when the board of the Finance Authority of Maine voted to reduce the amount of a bond it would sell on Thermogen’s behalf from $25 million to $16 million. Then on July 1, CEI Capital Management withdrew $20 million in expected financing through tax credit programs.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story