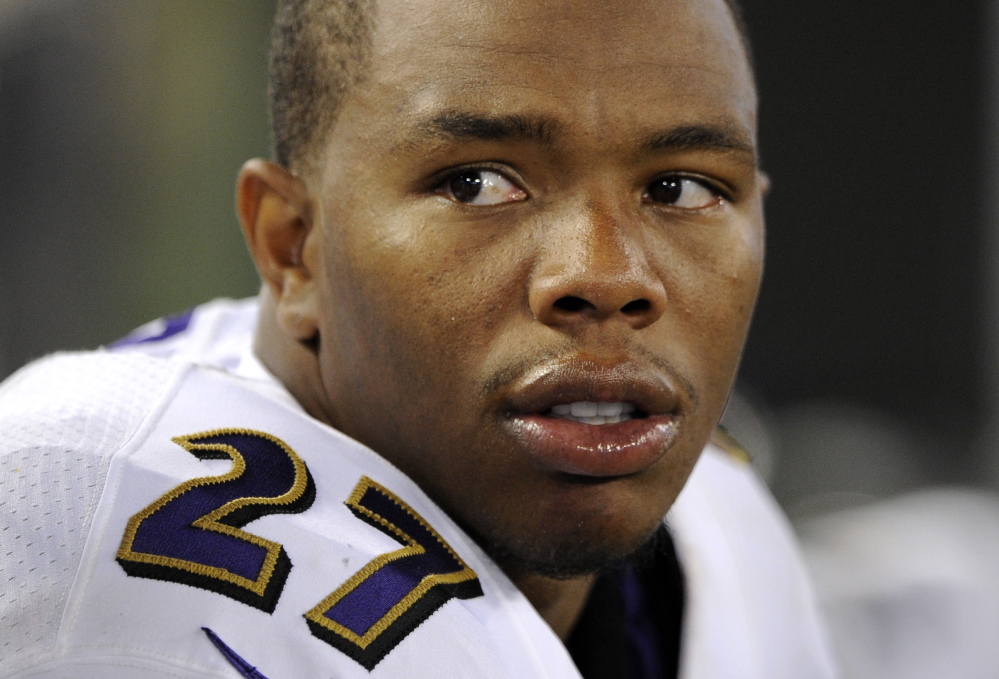

Daryl Fort watched the video along with the rest of America. He saw Ray Rice punching out the woman he loved and felt sadness and grief. A high-profile football player was caught in a violent act.

Fort took it personally. A former University of Maine football player, he has spent the past 15 years talking with male athletes and military personnel about their behavior with women. That’s thousands of hours spent asking some of the world’s toughest and most competitive men to turn to their vulnerable side when their relationships with women or children reach flash points.

Instead, Rice, the former Baltimore Ravens star, is shown throwing a hard right fist into the head of his fiancee in an Atlantic City casino elevator. Minnesota Vikings running back Adrian Peterson is indicted after allegedly taking a switch to his 4-year-old, leaving ugly welts. Jonathan Dwyer, an Arizona Cardinals running back, allegedly head-butts his wife because she refused his sexual advances.

Here we go again. Allegations of domestic violence, child abuse and brutish behavior. The cycle of violent acts plays out on the national stage and even here in Maine. Dominant male athletes pitted against women and children who can’t defend themselves. Education and talk of societal change is everywhere but the results are hard to find.

If Fort, 45, has committed so much of his working life as an advocate against gender violence, how does he reconcile Rice, Peterson and Dwyer? Not to mention Jovan Belcher, another former UMaine football player, who murdered the mother of his baby daughter in 2012 before taking his own life.

“I also have a little bit of hope,” said Fort, sitting in the living room of his Portland home. “I’m getting to hear that we can’t afford to let this be a moment in time that slips away without taking action.”

Fort is not the only one with hope in the face of troubling incidents. A sampling of educators and others in Maine shows they are determined to help prevent further violence by assessing what’s gone wrong and increasing their efforts to raise awareness among male athletes.

‘BROKEN PARTS OF OUR SOCIETY’

Robert Dana, the University of Maine’s vice president for student life, says he was shamed and frightened by the Rice and Peterson incidents. Shamed, because he is a man and this is not how men should act. Frightened, because he believes these are “reflections of broken parts of our society. We have to redouble our efforts to change the culture for men.”

Dana spoke, knowing the memory of Belcher’s murder-suicide in December 2012 is still fresh. Belcher was a Maine graduate and celebrated football player when he shot Kasandra Perkins in their Kansas City home and then took his own life in front of Kansas City Chiefs management at Arrowhead Stadium.

Last winter, UMaine running back Zedric Joseph was charged in the stabbing murder of a friend of his ex-girlfriend in Florida. Two years earlier, Joseph was arrested and charged with domestic assault against that girlfriend, Vashti Laurore, the mother of his child. Joseph is awaiting trial in Florida.

Last spring, UMaine hockey player Ryan Lomberg was charged with an assault after an altercation with another student at an off-campus residence in Orono. He pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of disorderly conduct and has since left the university.

Dana denied feeling weary with the constant battle to lead male athletes on his campus away from bad behavior. “We can’t let up. At our base, we know people are good. Sometimes I feel we need a quiver of a hundred arrows to target the problems.”

‘SAME OLD CYCLE OF VIOLENCE’

Al Bean, athletic director at the University of Southern Maine, said he felt “disgusted and disturbed” at the recent examples of bad behavior coming out of the NFL.

“It’s difficult stuff to process,” he said. “I look at the lack of civility today and the lack of caring and concern for others. When did we lose our spot on the track so this stuff (bad behavior) is acceptable?”

Bean has turned to his staff and outsiders for support. Fort appeared on campus over a recent two-year period to talk with athletes on individual teams.

“The effort is there to be on top of potential problems,” said Bean. “It’s the same old cycle of violence.”

He and his coaches hear from female athletes who have been hit by boyfriends. Bean has had students tell him of being beaten by parents.

“If you’re fortunate, you’ll get someone to talk. Others will do everything they can to hide what’s happening. It’s always terrible when you can get blindsided. You want to have the opportunity to help.

“There’s more students coming to us with problems than ever before. It’s a different world.”

USM partners with Maine Medical Center in Portland in surveys to gauge mental health and abuse issues among its student-athletes. Bean continually brings in social activists, counselors, teachers to speak to the student-athletes.

SEEKING PEER LEADERS

Fort has answers. He is disarming and articulate but understands that at the end of the day, someone has to listen and learn. He just returned from Baylor University, where he spoke to more than 500 athletes from a stage. He had to overcome the feeling that a moat separated him from his audience. He prefers individual team or staff gatherings where a presentation morphs into a conversation.

Fort tries to identify the peer leaders or hopes they identify themselves during the hour or so he spends with them. All it takes is one or two to connect to what he’s saying. He remembers a tough Marine master sergeant at Camp Pendleton in California initially saying the group discussion was a waste of his time. Later he came around to the message and became the ally Fort sought.

In 2006, former Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Brett Myers was arrested for punching his wife on a street in Boston. At spring training the next year, Fort and a colleague spoke to Phillies players. As they entered the room, Fort could hear over and over: “Thanks, Brett. Thanks, Brett.”

Meaning, the meeting was mandatory and the players had other things to do.

“It didn’t start out that way, but it turned into a very productive meeting,” Fort said.

Fort earned a degree in political science and worked for former representative and governor John Baldacci for 14 years on public policy issues. His commitment to social issues came about when he saw others try to change the culture of male athletes. A black man, Fort has experienced the bigotry of color and sees parallels with the bigotry of gender.

“I’ve often asked a group of guys who have no issues referring to women (with a disparaging term) how they would respond to a group of white guys using (a racist epithet) to describe their teammates of color. Most groups consider the racially bigoted term unacceptable because, they will say, the word has a history and current meaning that is derogatory. It’s degrading to black people.

“Well, doesn’t the (term toward woman) carry the same derogatory status both historically and in current times?” Fort said in a 2013 question-and-answer interview about sports and hypermasculinity for Voice Male Magazine.

“A lot of where I’m coming from rests on the platform and backs of those who came before me,” said Fort on Friday. “A lot of their work fell on deaf ears.”

DO TEAMMATES HAVE THEIR BACKS?

Belcher’s actions horrified the country. In the aftermath, Chiefs quarterback Brady Quinn tried to make sense of what happened. “When you ask someone how they are doing, do you really mean it? When you answer someone back how you are doing, are you really telling the truth?”

Fort says that’s at the heart of addressing the problems. In the 2013 Q&A he says, “Locker room culture doesn’t allow its male inhabitants to ask for or offer certain types of emotional support. It’s labeled ‘feminine’ and that’s the last thing many men want associated with their reputation especially among other men.”

So, asks Fort, do teammates really have their backs?

Belcher was a member of the Male Athletes Against Violence group at the University of Maine. It’s a select group, formed in 2004 by Dr. Sandra Caron, a professor of family relations and human sexuality. Not every male athlete who asked to join could. Caron hand-picked those who were committed to the mission. In any given year, the group might have five members or a dozen.

“The message we hope to convey is that men can be part of the solution by taking a stand against violence, sexism and by speaking up when they see or hear about such situations,” Caron said in an email. She didn’t respond to a follow-up email asking about Belcher’s role in the group.

Coach Jack Cosgrove saw Belcher’s commitment to his teammates and to Male Athletes Against Violence and also saw his player’s less-than-successful relationships with women. A request to speak with Cosgrove was denied Thursday; the university said that Dana would be the only voice speaking for the athletic department on this issue.

Caron said the Rice video has forced people to confront his actions and focus on the abuse of a man’s power over a woman. “Sadly, too often the discussion focuses on the victim. Perhaps the NFL will consider implementing a program similar to ours.”

‘TRYING TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE’

Gerald McLemore, who was a leading scorer for Maine’s basketball team, joined Male Athletes Against Violence about five years ago, feeling he was fortunate to have been chosen. “I wanted to give back to my university,” he said Thursday from the Maine Red Claws office in Portland, where he works as an account executive.

“We’re in a time of a lot of violence and we wanted to go into schools to talk to younger kids because they’re more impressionable,” said McLemore. “We’d read them the book ‘Hands Are Not for Hitting.’ Other times we’d meet as a group with Dr. Caron and talk about what was happening on campus, what we’re hearing and how we could help.”

McLemore graduated with a degree in communications and hasn’t left Male Athletes Against Violence behind. Through his initiative, the Red Claws are partnering with the Maine Coalition to End Domestic Violence for a Feb. 7 game at the Portland Expo with the Westchester Kings, an expansion NBA Development League team from White Plains, New York. It will be a jersey night, with players wearing customized shirts drawing attention to violence against women.

McLemore is 25, only two years younger than Rice – and Belcher, at the time of his death. If someone or something failed those two athletes or if they failed themselves, it doesn’t faze McLemore.

“People are unpredictable, we’re all human,” he said. “That means we need to keep trying to make a difference.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story