Doctors in Maine are reporting a record number of cases of anaplasmosis, a disease transmitted by tick bites that is lesser known than Lyme disease but can also have serious health consequences if not diagnosed and treated promptly.

Anaplasmosis is caused by a bacteria carried by infected ticks, and it leads to a variety of symptoms in humans, including fever, headaches, muscle pain and nausea. Antiobotic treatments can cure the disease, but if left undetected, it can lead to serious health problems, especially among people whose immune systems have been weakened by other conditions.

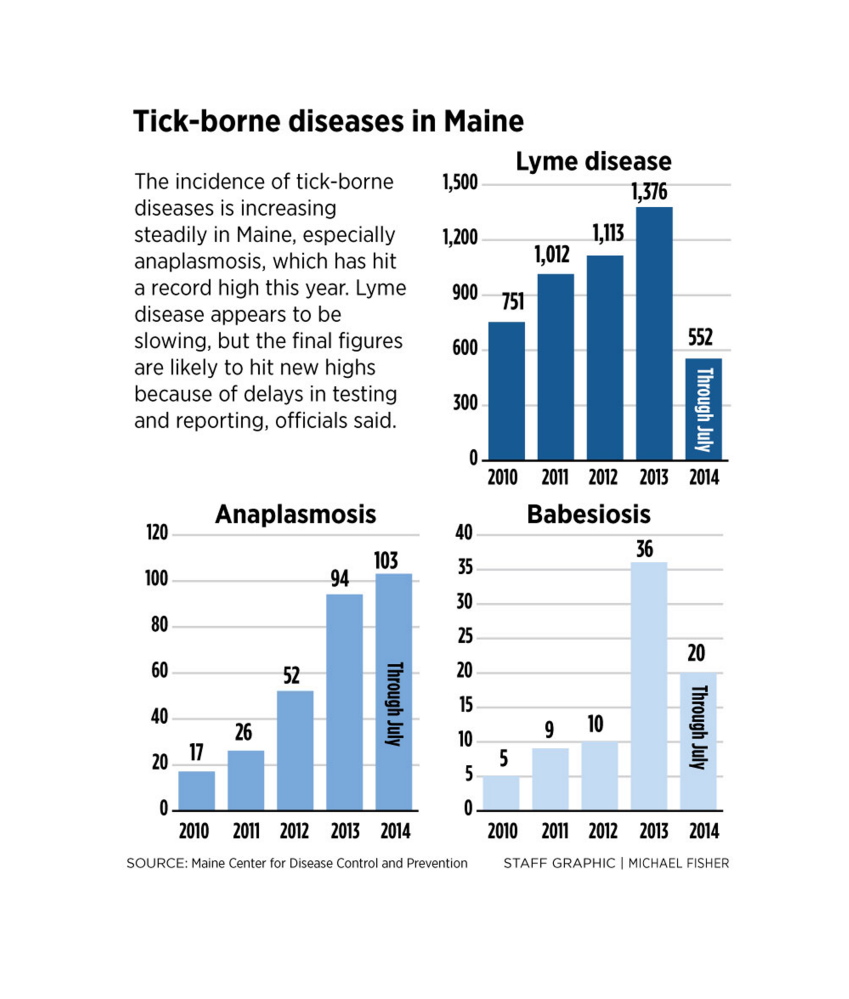

Over the first seven months of 2014, the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention has tracked 103 cases of anaplasmosis. That is already more than the 94 cases that were reported for all of 2013.

The jump is part of an overall increase in tick-borne diseases in Maine, which experts attribute to a continued increase in the deer tick population and growing public awareness of the threat of disease.

Babesiosis, another tick-borne disease, is still relatively rare but is also trending upward. So far in 2014, there have been 20 reported cases, compared to 36 for all of 2013.

The numbers for Lyme disease, the most common tick-related disease, are not nearly as high, although that could change. Through July, there have been 552 reported cases, compared to 1,376 for 2013, but Lyme disease often takes several months to be officially classified, so this year’s number is expected to rise considerably.

“A lot of this is just more education and awareness,” Maine CDC Director Sheila Pinette said, adding that people are much more likely to be tested for tick-borne disease if they feel they have been exposed.

The CDC issued a statewide alert to health care providers, school nurses and others last week reminding them to be on the lookout for symptoms of these diseases.

The prevalence of Lyme disease has been steadily increasing in Maine over the last decade. In 2003, there were 175 cases. Last year’s total of 1,376 was the highest on record in Maine.

Anaplasmosis and babesiosis are less common, but the increase in prevalence of those diseases mirrors the track Lyme disease has taken over the last five years.

In 2009, there were 15 cases of anaplasmosis and 3 cases of babesiosis on record. Since then, the numbers have steadily risen. This year is already a record year for anaplasmosis and, if the trend holds, the same will be true for babesiosis.

Many Mainers already are well aware of the dangers of Lyme disease, which can lead to meningitis, encephalitis and sometimes heart blockage.

Anaplasmosis, marked by fever, headaches and body aches, and babesiosis, marked by extreme fatigue, chills, sweating and anemia, are usually not as severe as Lyme disease. However, in cases where the infected person has a compromised immune system, the effects can be severe or even fatal.

“The good thing is that they can be treated with antibiotics,” said Jim Dill, pest management specialist for the University of Maine Cooperative Extension. “That’s why, when we have a tick bite, we always tell the individual to contact their physician, especially if people find a tick that is attached and it has started to feed.”

Dr. Robert Smith, principal investigator for Maine Medical Center’s Vector-Borne Disease Laboratory, said he’s treated patients for all three diseases this summer.

“There are clearly more cases of certain diseases over the last few years and I think awareness probably plays a big role,” he said.

Late night talk show host David Letterman revealed to his audience in 2009 that he contracted anaplasmosis, likely from a tick bite from sleeping in a tree house with his son.

Smith said people who are older or have immune deficiencies are more susceptible to serious symptoms or even hospitalization.

On the other end of the spectrum, he said, there are people who never know they have a tick-related disease.

“There is certainly still under-reporting going on,” Smith said.

Deer ticks are typically smaller than the more common dog tick and are more prevalent in woodland or brush-covered areas.

Every winter, many ticks die off, but during the past winter, heavy snowfall acted as a barrier that insulates the ticks and allowed them to survive bitter cold temperatures.

Maine also has seen an increase in winter ticks, a separate species, that is affecting the moose population. The state announced earlier this summer that it would award 1,000 fewer moose permits to help protect the population.

Coastal Maine is considered part of the range of the lone star tick, a species distributed more widely in the southern states that can transmit another disease, known as ehrlichiosis. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control reports that five cases of this disease were reported in Maine this year, but state public health officials say they believe that the cases may have originated out of state.

The lone star tick has also been blamed for transmitting a bacteria that causes an allergic reaction to red meat. However, the CDC does not address the allergy in its public health data and website on the tick.

The increase in Maine’s tick population and the corresponding spike in related diseases underscores the need for a dedicated laboratory, said Dill, something that what would be created if Question 2, the first of six bond questions on the November ballot, passes.

Voters will be asked to support or reject an $8 million bond that would build an animal and plant disease and insect control laboratory at the University of Maine that would monitor health threats related to mosquitoes, bedbugs and ticks

“Right now, all we can do is identify the tick. We can’t really test the tick to see what it’s carrying,” Dill said. “A new facility would allow us to do testing right here in state, which would have a big impact on public health.”

Eric Russell —791-6344

erussell@pressherald.com

Twitter: @PPHEricRussell

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story