Mainers increasingly question the safety of vaccines, and the state now has one of the highest rates of unvaccinated children in the United States.

The number of children entering Maine’s kindergarten classrooms without all of the required shots has jumped by about half in the past decade, to about 600 statewide, because parents philosophically object to vaccines.

Parents and health officials speculate that the trend is driven by a large body of anti-vaccine literature claiming the shots are unsafe, Mainers’ sense of independence, and parents’ desire to do what’s best for their children. But public health advocates worry that diseases common decades ago that were nearly eradicated could return.

Yarmouth Dr. Laura Blaisdell, a pediatrician who is teaming with MaineHealth to research why some Mainers are choosing to forgo vaccines, predicts an outbreak of measles or pertussis will erupt in Maine. The state experienced its highest number of pertussis, or whooping cough, cases in decades in 2012, and pertussis numbers in 2013 remained high compared to recent decades.

“It’s not a matter of ‘if.’ It’s really just a matter of time, of when it will happen. These are diseases that will come back,” Blaisdell said. “It will take the death of children for people to understand and realize the merits of vaccines.”

Blaisdell said doubt about the safety of vaccines has spread from the fringes to typical parents who have read sophisticated anti-vaccination messages on the Internet. The anti-vaccination movement started in the late 1990s, stemming from a study linking autism to vaccines that has since been debunked. National surveys report that people choosing to opt out of vaccines tend to be upper middle class and educated, and autism is only part of the reason for the skepticism.

Anti-vaccine advocate Ginger Taylor, 45, of Brunswick said the free market should dictate what vaccines, if any, people choose for their children.

“The jig is up. The system is broken,” Taylor said. “If they want to live in happy-land, in a world where vaccines are completely safe, that’s up to them.”

But Blaisdell said patients who doubt vaccines are most often not anti-vaccine crusaders, but people who are misinformed.

“We shouldn’t vilify them. These are reasonable people looking to make decisions with the best information that they have,” Blaisdell said.

The opt-out increase in Maine is entirely accounted for by the number of people signing philosophic exemptions to vaccinating their children, as opposed to religious reasons, according to the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Blaisdell is part of a group of Maine medical professionals trying to stem the anti-vaccination tide by educating the public and warning parents of the dangers of leaving their children unvaccinated. One of the leading efforts is vaxmainekids.org, a public health education partnership between MaineHealth and the Maine Immunization Coalition, an advocacy group made up of doctors, nurses and other medical professionals.

The message, if it succeeds, will take time to resonate, public health officials say.

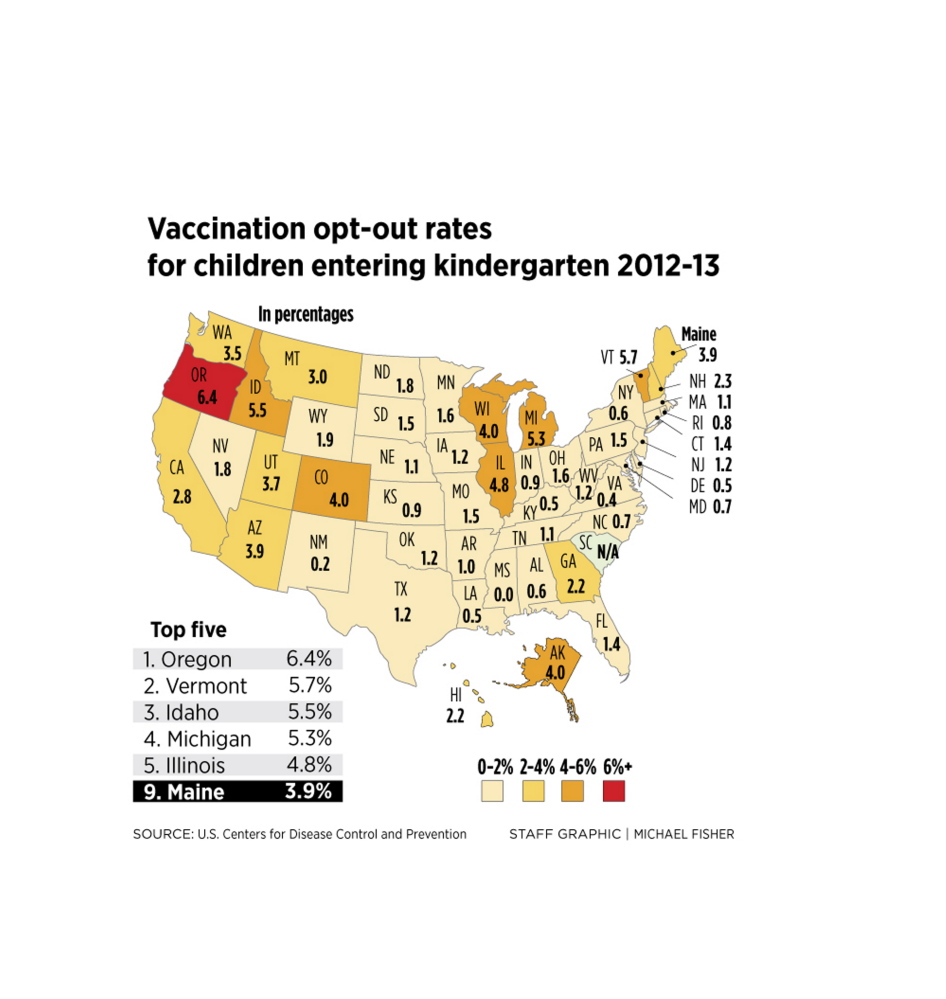

Maine’s opt-out rate for children entering kindergarten – 3.9 percent – is the ninth highest in the country, according to a 2013 report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While less than 4 percent may not sound high, vaccines are most effective when nearly everyone is immunized. When even 5 percent to 10 percent of the population opts out, what is known as “herd immunity” can be compromised, according to the CDC.

In 2012, Maine experienced its highest rate of pertussis since at least the 1960s, with 737 cases. The numbers declined to 330 in 2013 but were still high compared to historical standards, more than twice as much as a few years ago. This year, with 181 cases through June 30, pertussis cases are tracking similar to 2013.

The numbers are worrisome, health experts say, and represent a danger even to those who have had their shots.

When herd immunity breaks down, even those who are immunized can be at risk, according to scientists. That’s because not everyone’s body responds to and is inoculated by the vaccinations, but widespread vaccination prevents the spread of disease to those who aren’t protected. Herd immunity also protects babies who are not yet old enough to get their vaccines. When the percentage of those opting out of vaccines climbs, the effectiveness of herd immunity declines.

MEASLES COMING BACK

Measles, while not a problem in Maine, with only one confirmed case in 2013, is starting to make a comeback nationally. The CDC has reported nearly 600 cases so far this year in the United States, more than 10 times higher than a typical year.

One in 1,000 children who fall sick with measles dies, according to the CDC.

Children can’t start receiving their measles vaccine until age 1. As an airborne infectious disease, along with pertussis, it’s extremely contagious, Blaisdell said.

“If you’re in the same room as someone who has contracted measles and you’re not vaccinated, you’re pretty much going to get measles,” Blaisdell said. “I wouldn’t want to see a baby with measles.”

Dr. Larry Losey, a Brunswick pediatrician, said “vaccines are a victim of their own success.” Because vaccines have done such a good job eradicating or greatly minimizing diseases, people forget about those past scourges and focus instead on imagined threats, he said.

Over time, the heroic image of vaccines – Dr. Jonas Salk developing the polio vaccine in the 1950s and earning the Presidential Medal of Freedom –has faded, Losey said. The polio virus infected 50,000 people or more per year in the 1940s and 1950s, before the Salk vaccine. Those who didn’t die were often paralyzed or had to receive treatment in “iron lungs.”

Ann Lee Hussey, 60, a South Berwick polio survivor who contracted the disease as a baby, a few years before the vaccine became widely available, remembers schoolchildren standing in line to get their vaccines, and how grateful parents were to have their children vaccinated.

“I remember adults talking about how much of a sense of relief it was to have the vaccine,” said Hussey, who can walk, but with difficulty.

Similarly, hundreds of thousands of cases of measles were reported annually in the 1950s, causing hundreds of deaths per year. But, after the measles vaccine was introduced in 1963, cases dropped to near zero.

And millions were infected with German measles – rubella – in the mid-1960s, with more than 11,000 babies dying between 1963 and 1965. After a vaccine was introduced in 1969, rubella also was nearly eradicated, according to the CDC.

Hussey said it galls her to see people voluntarily forgo vaccines. In countries that don’t have easy access to the vaccine, polio is still killing and maiming people.

“Quite frankly, I think they’re being very selfish at the expense of children. I can’t imagine us going backwards,” said Hussey, who has volunteered in Africa to help administer the polio vaccine.

STALWART OPPOSITION

In Blaisdell’s office, 1-year-old Kyle Stackhouse looked suspiciously at two nurses hovering by his belly, despite their soothing words and compliments about his curly hair.

The nurses quickly stuck needles in his legs, and he cried until his face turned red.

Kyle received vaccines for MMR (measles, mumps, rubella), pneumococcal and Hib, which protects against meningitis and epiglottis.

Kyle’s mother, Leanne Stackhouse of North Yarmouth, believes strongly in vaccines. She said it’s maddening to know that public health is being compromised based on rumors.

“Are these people who think they know more than the scientists getting their information from scientific journals or the bathroom wall of the Internet?” she said.

Why so many Mainers are choosing not to vaccinate their children is unclear. Blaisdell’s research is not finished, and what data are available are incomplete. Blaisdell is lobbying the Maine Department of Health and Human Services to keep more detailed records of vaccinations, including specifically what vaccines people are choosing to skip, in order to better understand the problem.

In Maine and 19 other states, people can choose to opt out of vaccines with a philosophical or religious exemption. The rate of people opting out for philosophic reasons has increased from 2.6 percent in 2004 to 3.8 percent in 2013, according to the Maine CDC. People citing religious reasons has stayed steady at around 0.1 percent.

States that share Maine’s higher opt-out rates seem to have little in common. They’re on both coasts and in the heartland, and they cross the ideological spectrum: Oregon, Idaho, Wisconsin, Michigan, Arizona. In Oregon, the kindergarten opt-out rate was 6.4 percent, the highest in the nation, and some pockets of Oregon report much higher rates, with nearly 20 percent of students entering school unvaccinated.

Within New England, Vermont and Maine have the highest percentages of people choosing not to vaccinate their children. The rest of the region has significantly lower opt-out rates.

Chelsea Kidd of Rockland, the mother of a 4-year-old boy, believes part of the reason is cultural, as Mainers take the organic, anti-chemical, anti-preservatives, “everything must be natural” mind-set to the extreme. She said she saw the prevalence of the movement among moms, not only online but in breastfeeding classes and other places she saw them congregate.

“It’s the Earth Goddess kind of thing. And Mainers can be so very stubborn,” Kidd said. “It’s like an entire culture. It’s scary the things people will believe in.”

Dr. David Katz, director of Yale University’s Prevention Research Center, wrote in an email response to questions that vaccine opposition tends to coalesce in certain populations.

“There are what we might call ‘granolas’ in the vernacular, people who believe nature is wise and benevolent and science is misguided at best, nefarious at worst,” Katz wrote. Other opposition includes “rugged individualists who simply don’t like anyone telling them what to do, conspiracy theorists, the poorly informed, and easily manipulated,” Katz wrote.

But for Taylor, the anti-vaccine advocate, the defining moment was when her son, now 12, regressed socially and developmentally when he was 18 months old, shortly after receiving vaccine shots. He became autistic, she said, and she blames vaccines.

“I have a vaccine-injured child,” Taylor said. She said no one has been able to provide any other explanation for her son’s autism. Researchers have not pinpointed a cause of autism but say genetics and environmental factors likely play a role.

Taylor said she started researching the topic and became convinced that most physicians giving advice to patients were not keeping up with vaccine research.

Taylor said Mainers are independent people “who don’t like being sold a bill of goods” and so are more receptive to anti-vaccine messages.

When parents come to a visit with entrenched views, Blaisdell said a five-minute conversation with a doctor is not effective.

“To have a good conversation about vaccines takes 45 minutes,” said Blaisdell, noting that doctors don’t have enough time to spend with each patient on the issue. “We don’t know how to approach a parent who is refusing our care.”

PLAYING CATCH-UP

Some parents choose to delay vaccines, concerned about overwhelming their children’s bodies with many vaccines given at once. A 2011 report for the Maine CDC said that according to national surveys, more than twice as many parents delayed vaccines for their children than refused them outright.

According to the U.S. CDC, there is no reason to delay vaccines, and the schedule is needed to provide children with maximum protection from the diseases. That agency recommends that children receive nine vaccines before age 18 months – including chickenpox, polio, pertussis, measles and hepatitis A, among others – with booster shots in future years.

“Children do not receive any known benefits from following schedules that delay vaccines. Infants and young children who follow immunization schedules that spread out shots – or leave out shots – are at risk of developing diseases during the time that shots are delayed,” according to the federal website.

Maggie Jansson of Brunswick, who has a master’s degree in public health, said she was “totally on the vaccine bandwagon,” but started to harbor doubts once she became a mother and read about vaccines.

“I have a distrust of the pharmaceutical industry,” Jansson said. “Chemicals are in everything.”

But Jansson said she does see the value in vaccines, so she decided to take a compromise route and delay the vaccines after she read a popular book by pediatrician Dr. Robert Sears. The book offers parents who are skittish about following CDC recommendations an alternative vaccine schedule. Jansson said her two children will be fully vaccinated by age 5.

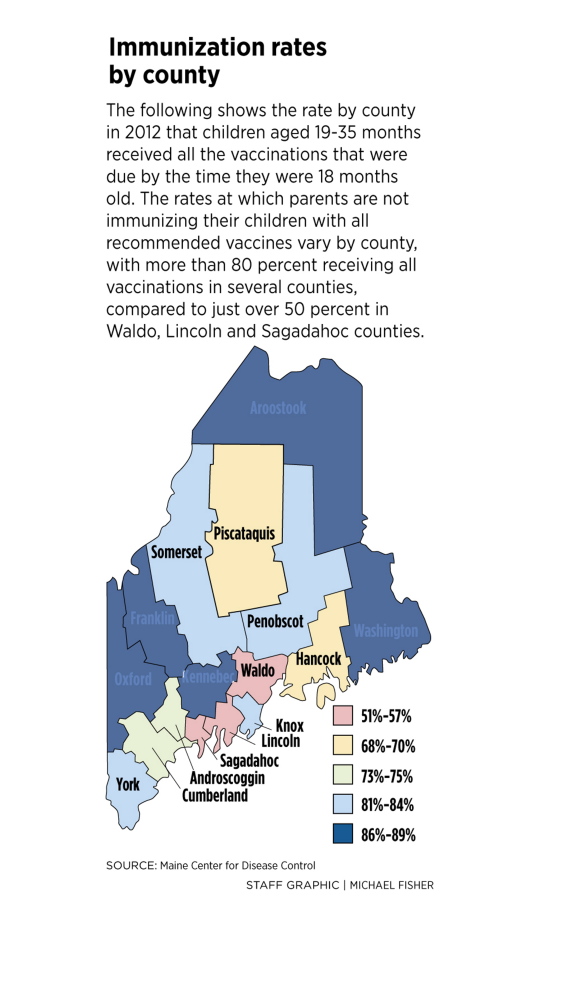

Data collected in 2012 by the Maine CDC show that parents of toddlers are far less likely to have their children caught up on immunizations recommended for age 18 months than those entering kindergarten. The data were collected by county, and there’s wide disparity of vaccine coverage depending on location. Waldo, Lincoln and Sagadahoc counties had less than 60 percent of children ages 19-35 months fully vaccinated, while Aroostook, Washington, Kennebec and other counties had rates at 85 percent or higher.

Jansson said she hasn’t been criticized by her doctor for delaying the vaccines.

Dr. Sheila Pinette, director of the Maine CDC, said parents are more exposed to vaccine messages once their children are in school. By seventh grade, the number of children who don’t have the necessary vaccines is about 2 percent or less.

“We’re providing catch-up vaccines for a lot of these children,” Pinette said.

FREEDOM OF CHOICE VS. PUBLIC GOOD

Pinette said cost can be a factor for parents who can’t afford the small co-pays some insurance companies require for vaccines. A state program that pays the entire cost of vaccinations was suspended for three years starting in 2008. It restarted in 2012.

Some say the state should make it more difficult for parents to opt out of vaccines. Now, all they do is sign a form, submitted to their child’s school.

Rep. Dick Farnsworth, D-Portland, House chairman of the Legislature’s Health and Human Services Committee, said he would be in favor of eliminating the philosophical exemption or making it more difficult to obtain one by requiring that a doctor co-sign or parents first have a conversation with a health professional.

A 2006 study by Emory University in Atlanta showed that states that make it more difficult to forgo vaccines have higher vaccination rates. Thirty states do not permit philosophical exemptions. Three states – California, Vermont and Washington – recently approved laws making it more difficult to opt out of vaccinations.

Anti-vaccination proponents last year put a bill before the health committee in the Legislature that would have required medical professionals to tell parents the ingredients in each vaccine and inform them of the philosophical exemption. It fell only one vote short of making it to the House floor, so Farnsworth said any attempt to strengthen the vaccine laws faces obstacles.

Farnsworth said it’s a classic case of freedom of choice versus the public good of vaccines. Because vaccines aren’t effective if people opt out, he said, the laws are necessary.

“It’s not just a personal decision of what you do with your own child,” he said. “Sometimes we need to do things for society as a whole.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story