ROME — Anastasia Paradis was bullied in school, enough so that her parents finally pulled her out and home-schooled her until high school.

When Carol Brunjes was an elementary school student in Bath, her teacher thought she should be in special eduction.

Both have disabilities that make physical activity difficult and it made them stand out.

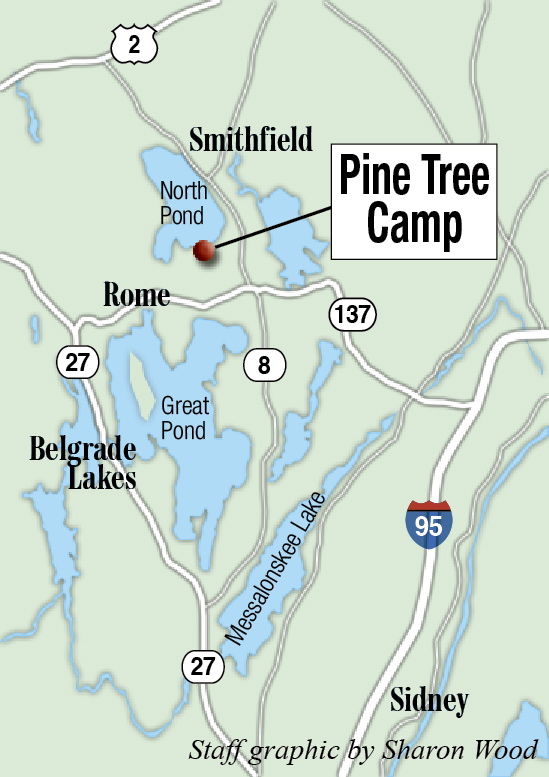

But as Paradis, of Anson, sat on her bunk Tuesday at Pine Tree Camp, about to begin her 10th summer there, disability was the last thing on her mind.

As she hunched over a sketchbook, drawing pictures of horses, her favorite subject, her thoughts were on whether she should change her horse’s name. He started as Pumpkin Patch, then as she got older, became Patches.

“Patches” was starting to sound juvenile every time it filtered through her hearing aids on the path into her 17-year-old ears.

“Maybe Apache,” she suggested, her lightly freckled face and sunny smile slightly at odds with her gray and black clothes, nose stud, multiple earrings and the skull-and-crossbones pendant that dangled from her neck.

But unique forms of personal expression are a part of the teenage condition and Pine Tree Camp is a place that takes it a few steps further, where young people with disabilities can, for a blissful week, know it’s OK to be themselves.

The camp is supported mostly by donations, which have been generous enough to finance an ambitious new capital campaign designed to bring the camp, founded in 1945, into the future.

Adam MacDonald, the marketing coordinator for the Pine Tree Society, walked past Anastasia’s bunk in Cabin 3, the first in a planned set of five new deluxe cabins that carry a sticker price of about $250,000 each.

Officially named Windover Cabin in recognition of the charitable foundation that funded its construction, Cabin 3 is a hybrid of the traditional camp bunkhouse and a fully accessible building. The cabin, which can accommodate 16 campers and six counselors, is separated by partitions into separate three-person sleeping areas. The doors are all wide enough for wheelchairs; the toilets are fully accessible and the climate control system keeps the air cool in the summer and warm in colder weather, which will allow the camp to extend its traditional season into the fall and spring.

Future plans include a fully accessible playground, complete with a customized swing that will work for a person in a wheelchair.

It’s all done to allow kids to be kids.

“For most of the campers, this is the one week of the year that they are not different,” MacDonald said. “Everyone is able to participate in the activities and no one is ever left on the sideline.”

This is the only chance some kids have an opportunity to go swimming or kayaking, aided by a trained counselor, an experience that may seem mundane to an adult but which is so exhilarating to the campers.

Here, where even the tree house is fully accessible and every activity is structured to leave no one on the sidelines, disabilities simply don’t matter.

“Everyone knows you’ve got some sort of internal struggle,” Paradis said.

Brunjes, 41, agrees.

In second grade, Brunjes’ teacher couldn’t reconcile her physical disability with the fact that Brunjes was as smart as any other student in the class.

That summer, Brunjes attended Pine Tree for the first time. At the camp, she said, no one cared how she walked; they only cared about her as a person.

“Here, you don’t have to worry,” she said as she sat at a picnic table at the camp Tuesday.

THE STRUGGLE

Paradis and Brunjes’ stories reflect the special challenges a person with disabilities can face, where acceptance comes slowly and prejudices can be deeply ingrained.

Paradis has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a hereditary disorder that wreaks havoc with the body’s connective tissues and expresses itself in many ways.

In the 1900s, some people with Ehlers-Danlos performed in circuses, showcasing their ability to stretch their skin far away from their body. The disorder can also affect hearing, eyesight and the joints.

Paradis’ skin is more fragile than that of most people — a long red scratch on her arm is from a relatively light contact with her dog, she said. Her thumbs are permanently dislocated.

From her first years in elementary school in Anson, Paradis was an easy target for bullies, in part because her muscles have to work extra hard to make up for the laxness of her joints. Her spine slumped and it was difficult for her to walk — she was sometimes confined to a wheelchair.

One day she brought a goose egg to school for show and tell, and one of her classmates pushed her down a short flight of stairs. The egg smashed.

The incident prompted her parents, Andrew Paradis and Samantha Paine-Paradis, to home-school her.

Without the social engagement that is part of the traditional school environment, Pine Tree Camp became an important part in Paradis’ socialization. She became close friends with another camper, Alyssa Briglio, of Lisbon, whom she met when they were 8 years old.

When asked what disability Briglio has, Paradis shrugged.

“I don’t know,” she said.

The question is unimportant to her because at Pine Tree, another person’s disability is one of the least interesting things about them.

In her sophomore year, Paradis returned to high school. While her peers treated her better than they had the previous decade, she still felt like an outsider.

“Some of them thought I just moved to the area,” she said. “I was like, ‘No, I live up the road from you and I remember you from when you were small.'”

There were also intentional slights, which she attributes to small mindedness.

“Mostly, the middle schoolers sucked,” she said. “They can be mean little buggers.”

That opinion was hardened one day when Anastasia saw a group of middle school students who had just gotten off the school bus she was riding jeering at her through the window. Once they had her attention, they imitated, in exaggerated fashion, the way she walked and the way she moved, her limbs hanging loose because her muscles were too exhausted to hold them tight.

RETURNING CAMPER

Brunjes can identify with Anastasia’s struggles to find acceptance.

Last week, she spoke animatedly about her own childhood experiences in Bath. She sat at a picnic table, the late morning sun glinting off the prosthetic leg extending from beneath her sun dress. Nearby, a group of counselors and campers kept up a Pine Tree Camp tradition by loudly cheering the car of each arrival.

In second grade, her teacher didn’t believe that there was any room in her classroom for disability.

Brunjes has cerebral palsy, which impairs the body’s central nervous system and makes body control difficult.

There was nothing wrong with her mind, but her teacher couldn’t see that. The teacher wanted Brunjes to be transferred to a special education class for those who couldn’t function in the classroom environment or grasp the subject material.

“She treated me like I was a dummy. And all the kids followed suit,” she said. “I believed them. I thought I was dumb. I had no self-confidence. I was in the lowest group for math, for reading.”

That summer, Brunjes came to Pine Tree Camp for the first of what would become 10 annual visits.

Outside of the camp, Brunjes was acutely aware of her unusual posture and gait.

“I tried so hard to walk normal,” she said. “I tried for every minute of every day.”

But Pine Tree Camp’s counselors treated her like they treated each other, a simple principle that marked a major turning point for a little girl with little self-esteem.

Returning to third grade, she said, she attacked her courses with renewed confidence and landed in the top groups for both math and reading. It was the start of a new academic career that saw her through high school and beyond. She got a master’s in deaf education from the University of New England, with a minor in chemistry, and earned a post-master’s certificate of advanced graduate study from New England College in Henniker, N.H.

Today, Brunjes, who once felt she wasn’t capable of the simplest math concepts, is a math teacher. She and her husband just bought a lakefront home in Mercer, just across North Pond from Pine Tree Camp.

It’s a good feeling.

“We’re living the life,” she said. “If it wasn’t for this camp, it would be different. I wouldn’t have had the confidence to continue my education.”

A BRIGHT FUTURE

Brunjes’ experience at Pine Tree Camp is at the core of the organization’s purpose, said Noel Sullivan, president and CEO of the Pine Tree Society, which operates the camp.

Most camps aren’t equipped with the staff and medical equipment needed to handle campers with disabilities, which creates liability issues for them.

But at Pine Tree Camp, every camper is as safe, if not safer, than they would be at home.

It’s a concept that can be difficult for parents to appreciate right away, Sullivan said.

“Parents ask if they can stay the whole week to keep an eye on their children,” he said. “Often, after a night or two, they say, ‘Well, maybe it is OK for me to go home.'”

The cost of the one-week camp is $1,900 per camper — on paper.

“I don’t think anyone’s ever paid that,” he said. “Some pay $100 if they can. Some pay nothing.”

Paradis is one more camper with a bright future.

A turning point for her came after a spinal surgery designed to help her support her own weight.

After the surgery, the doctors told her she shouldn’t ride Patches, or any other horse, ever again. It was a devastating pronouncement for Paradis.

Not willing to make the sacrifice and firm in her belief that Patches could only be a help, she wouldn’t give up.

“I trust him with anything,” she said fervently.

Her parents reluctantly supported her decision to keep riding, swayed in part by the argument that the exercise functioned as a kind of physical therapy for her back. In fact, her back muscles have been helped significantly by the work.

It’s been a while since Paradis has needed a wheelchair.

After unpacking her items into a bunk in Cabin 3, she wandered up to a group dining hall, where dozens of campers, counselors and parents were making lunch sandwiches and grabbing cookies.

Afterwards, she stood out on the porch, sketching a wildcat while chatting with her friend Briglio, who was making a set of green bracelets on a small worktable that folded into the front of her wheelchair.

Paradis has started to think about a career.

She plans to go to the New England School of Communications to continue studying photography, possibly to become a photojournalist.

She will turn 18 in August, which means that she will no longer qualify to participate in the camp’s child program. She has lots of options for how she could spend next summer, but Pine Tree Camp has become, for her, an opportunity to make the world a better place. She’s hoping to become a counselor.

Her long hours on the horse — coupled with her experiences at Pine Tree — have helped give her a well-developed spine.

“I have the strength now,” she said.

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling — 861-9287

Twitter: @hh_matt

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story