Being a teacher, my wife, Bonnie, frequently comes up with puzzling questions; and the other day as she was gazing at the astronomy calendar in the kitchen she said, “Is Jupiter still a planet?”

“Well,” I said, “you can see it in the west after sunset right now. It’s pretty bright.”

Not that being able to see it proves anything — you can see lots of stars, too, which are not planets. But to take the via negativa, you cannot, on the other hand, see Pluto, which used to be a planet. It’s way too dim, at magnitude 14.1, to spot even with a backyard telescope, while Jupiter is shining at an eye-dazzling magnitude minus 2 now.

The crafty subtext of Bonnie’s question, of course, is that Pluto got struck off the list of planets in 2006 by the International Astronomical Union and reclassified as a “dwarf planet.” Human nature being what it is, this upset a lot of people.

Pluto was discovered in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh, combing through photographic plates at the Lowell Observatory in Arizona, and was officially named by 11-year-old Venetia Burney, of Oxford, England, on May 1 that same year. Schoolkids and teachers since then have known Pluto as the ninth planet of our solar system. It’s just a fact of nature.

As the 1930s turned into the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, though, the facts of nature, well, sort of evolved. With improving instruments and accumulating mathematical data on the planets and their moons, some astronomers began to suspect there was more to the solar system than meets the telescope. That turned out to be the Kuiper Belt, or the range of space beyond the orbit of Neptune containing thousands and thousands of mostly (so far) small bodies, and the Oort Cloud, the range of space beyond the Kuiper Belt thought to contain comets.

The first Kuiper Belt object beyond Pluto was identified in 1992. It’s nowadays estimated to be about 65 miles in diameter, so it was never a challenge to the idea that Pluto (being about 1,430 miles in diameter) is a planet. But in the 2000s, trans-Neptunian objects in Pluto’s size range started to be located and measured, validating many astronomers’ theory that the nine classical planets — Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto — are not alone.

By 2006, a hot debate was underway among professional astronomers about whether Pluto should continue to be classified as a planet, because if it was, then it was clear there eventually were going to be a lot of planets.

As of May 6, Caltech astronomer Mike Brown (who wrote a book titled “How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming”) reported on his website that there are 10 objects that are nearly certainly dwarf planets, 27 objects that are highly likely to be dwarf planets, 47 that are likely to be dwarf planets, 82 that are probably dwarf planets and 346 objects that are possibly dwarf planets.

The largest of these, Eris, is either slightly larger than Pluto, about the same size as Pluto, or slightly smaller, depending on whose measurements you go by. The third-largest, Makemake, is about 884 miles in diameter. Others, slightly smaller, are Haumea, Quaoar, Sedna and Orcus.

How are the planetary astronomers supposed to talk about Pluto, Eris and Makemake in the same category with Jupiter, which is almost 89,000 miles in diameter, but in a different category than our own moon, which is larger than Pluto by about one-third? And what is a science teacher supposed to do — make kids memorize a list of potentially hundreds of planets? And how about what everybody learned in the fifth grade? Is nothing sacred?

The IAU tried to quell the confusion by revising the definition of a planet. Amid much debate, they passed a resolution stating that a planet is a celestial body that orbits the sun; has enough mass to be nearly round in shape; and has cleared the neighborhood of its orbit, meaning its gravity is enough to have pushed everything sizable out of its way.

This did not work out too well, though. A lot of astronomers objected to at least some of the criteria. So they added a category, “dwarf planet,” for round objects orbiting the sun that have not cleared their neighborhoods and are not satellites. Pluto, Eris and Makemake are dwarf planets. The moon is not, because it’s a satellite of Earth.

This still has not satisfied everybody. For one thing, it means that Charon, which is conventionally called a moon of Pluto, is actually a dwarf planet because it isn’t technically a satellite — the two orbit each other. And is Ceres, which is a large round object in the asteroid belt, an asteroid or a dwarf planet?

Luckily there is no debate at this time about the planethood of Jupiter, Saturn and Mars (which you can also see shining brightly in the night sky this May) and the other five.

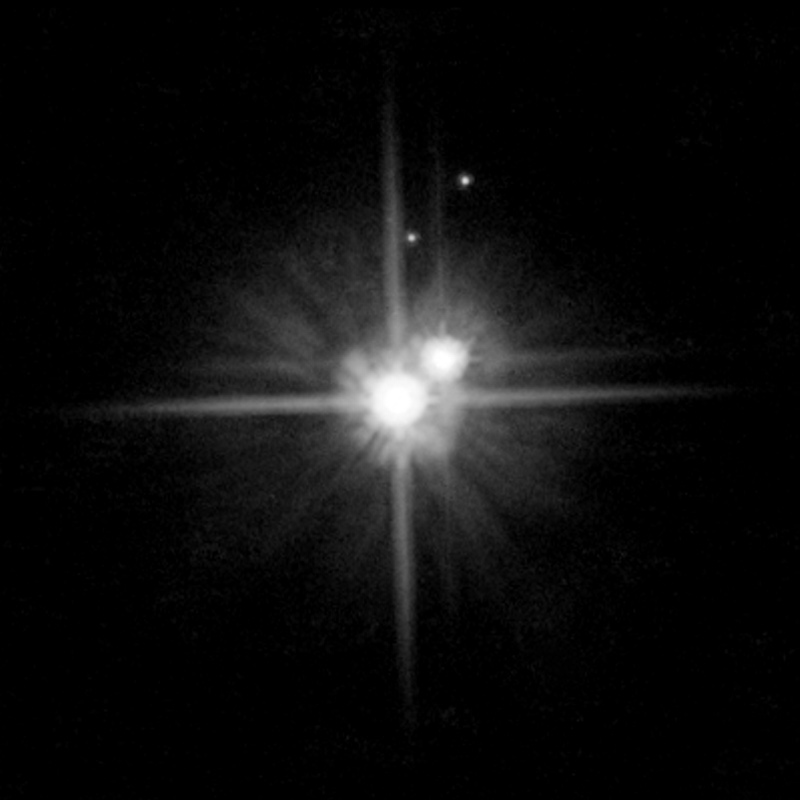

“Yes, Bonnie,” I said, to reassure her English-teacherly confidence. “There is a planet Jupiter. But if it was just 13 times larger, it could be a star.” A brown-dwarf star, that is.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy. His writings on the stars and planets are collected in “Nebulae: A Backyard Cosmography,” available online and by writing to him at naturalist@dwildepress.net. Backyard Naturalist appears the second and fourth Thursdays each month.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story