“You’re up, Red!” 70-year-old Rene Field called to his bowling partner, Red Ryer.

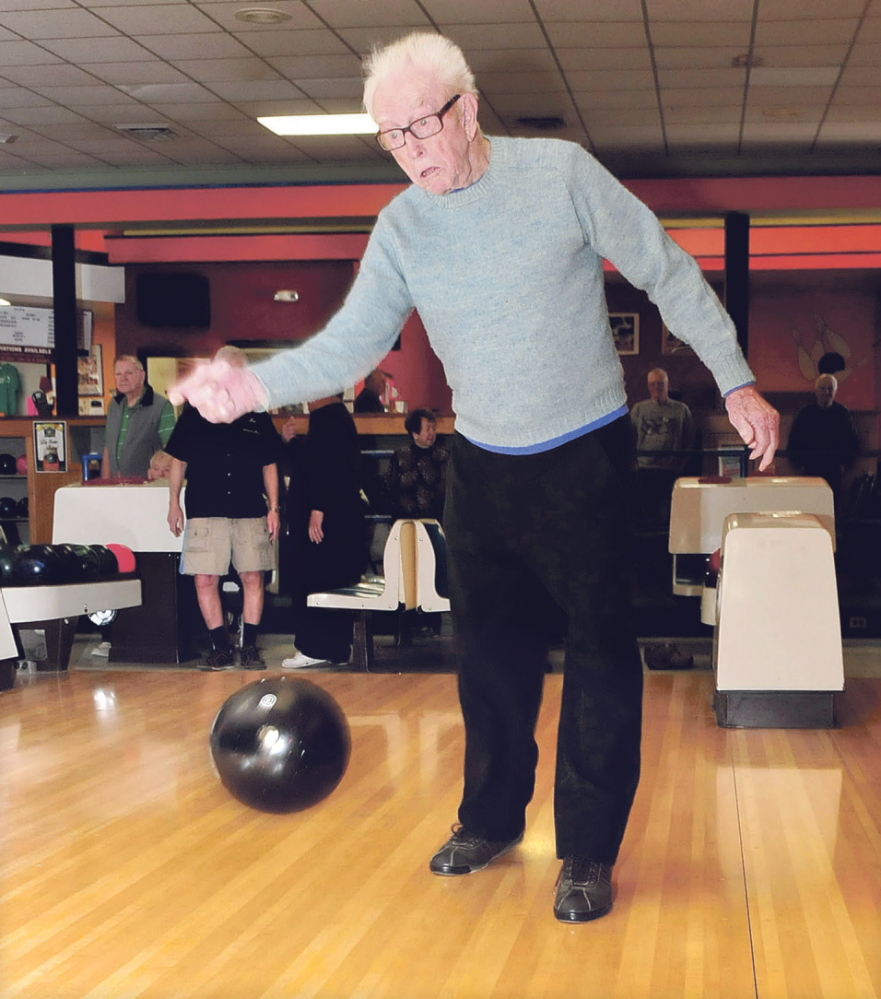

Ryer, 98, stepped up to the lane, plucked his 10-pound black ball from the tray, aimed hard and dropped it with a heavy thump.

The ball traveled down the hardwood lane, knocking down all but two pins.

He picked the ball back up and tossed it again, striking the final two.

At that, Cecil Hall, 79, congratulated Ryer and shook his hand.

“Hey Red — good spare!” he said.

It was Monday morning and the men were at Sparetime Recreation on West River Road in Waterville, where they bowl as part of a 68-member seniors league called Primetimers. About half of the members are 75 and older.

Ryer, the oldest, has been bowling about 40 years and is famous around the league.

“We do think an awful lot of Red,” secretary-treasurer Mary Pennacchi said. “He’s a great guy.”

Ryer, a member of the Pinpushers team, might blush at that compliment. After all, he’s just a regular guy who has worked hard all his life, doesn’t drink except maybe having a glass of wine now and then, and smoked only a short time during his long life.

“I was working in Augusta one day at a business place, doing sheet metal work, and I had heart palpitations,” he recalled. “So when I got home that night, I put all my smoking equipment in the cupboard and closed the door. I never opened it. I never smoked again.”

That was more than 60 years ago. Since then, he’s been healthy as a horse.

At 145 pounds and 5 feet, 8 inches tall, Ryer is lithe and fit, wears glasses and has blue eyes and a shock of white hair that is reddish only at the temples — a clue to why he bears the nickname “Red.”

He actually was born Bernard Ryer, in 1916, in Mars Hill.

“My family was working on the farm,” said Ryer, now of Fairfield. “My mother was doing the cooking and my father was working in the potato fields. At that point in time, we lived in a cabin on the edge of the potato field. I’m still not crazy about picking potatoes. We picked so many of them.”

He likes to tell the story about the first cow he ever saw, when he was 3.

“A cow was tethered there on the lot, and she used to stare at me all the time. I couldn’t stand that. I threw a handful of small pebbles at her, but they maybe got halfway there because my arm was so little. She didn’t blink an eye. I moved away from there as fast as I could.”

That incident marked the beginning of a lifelong love of nature. In fact, Ryer has written and self-published four books of poetry, mostly about nature.

He is fascinated by the natural world. When he was very young, he said, his family moved to the south end of Maranacook Lake, in Winthrop.

“The lake edged right to the road upon which my house was placed. I was fascinated by the lake. I used to walk around it a lot. One night I was walking around the edge of the lake just to see what was going on and I heard a clicking, clicking, musical-type noise. The lake had formed what I later learned was a common phenomenon in many parts of the world. The ice formed little jagged cups, and when the breeze blew, they all clicked together. It really made beautiful music. I was between 4 and 5 years old, and even then I was very interested in nature. I really enjoyed that trip at the lake. I never told anybody about that for 90 years.”

Ryer loves telling stories, including one that reveals his humorous side.

“When I was young I had a friend, a little Polish boy about my age but a little smaller. I wasn’t very big. We were in class in school and one day the superintendent came in and the teacher wanted to show us off, so she said, ‘Who can name the three most common vegetables in the garden?’ and we answered, ‘Let us turn up and pee,’ which earned us dismissal from school for the day — and dismissal wasn’t much of a punishment.”

After graduating from Norridgewock High School in 1933, Ryer worked in a shoe factory for a while and then was a roofer. He started making kitchen cabinets, and then served in the Army Air Forces as a radar mechanic.

“After (World War II), I started working for myself. I developed a line of cabinets and did a little in Waterville, but mostly in Fairfield, where I moved and had a shop. I made kitchen cabinets. I’ve got a lot of kitchens around that people are still using. I did some good work.”

He married and had two children. Betty, his wife of 52 years, died about 20 years ago. His son, Michael, who attended and worked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, died at 62.

“I had two extremely intelligent children. I think my wife must’ve been pretty smart. My daughter, Sharon, she’s a real jewel. She taught kindergarten for 38 years. Now she’s retired. She and her husband have a very prosperous construction business, building houses, garages.”

Ryer said he never would have retired had his eyes not deteriorated, for one thing.

“For another, I’m old,” he said. “I started reading when I was 5 years old in the public library in Winthrop and I never stopped until my eyes went bad a couple of years ago. I read quite a lot of nature books.”

The key to longevity and good health is simple, according to Ryer.

“I slept every night and got up and went to work every morning. That’s my secret. I’m a very moderate eater. I like all kinds of food. I eat a lot of vegetables and I eat probably less meat than most people. I like meat. When I was growing up, my mother cooked with an eye to raising some good children, and she was pretty successful at it. I had a brother and two sisters.”

Treating people well, not boasting and staying engaged also are key, he said.

“I mind my own business. I’m very adept at minding my own business. The most important thing in life, I believe, is to have many interests — not confine your thinking to one area. Be open-minded.”

And at that, Ryer acknowledges he is a happy man.

“I decided, I guess, a long, long time ago if you can’t fight it, don’t try. If you’re in an impossible position, take a different direction. It’s reasonable, and right now, the way the world is, you don’t get exposed to a lot of reasonable stuff.”

Amy Calder has been a Morning Sentinel reporter 26 years. Her column appears here Mondays. She may be reached at acalder@centralmaine.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story