AUGUSTA — Military culture values toughness, stoicism and self-sufficiency.

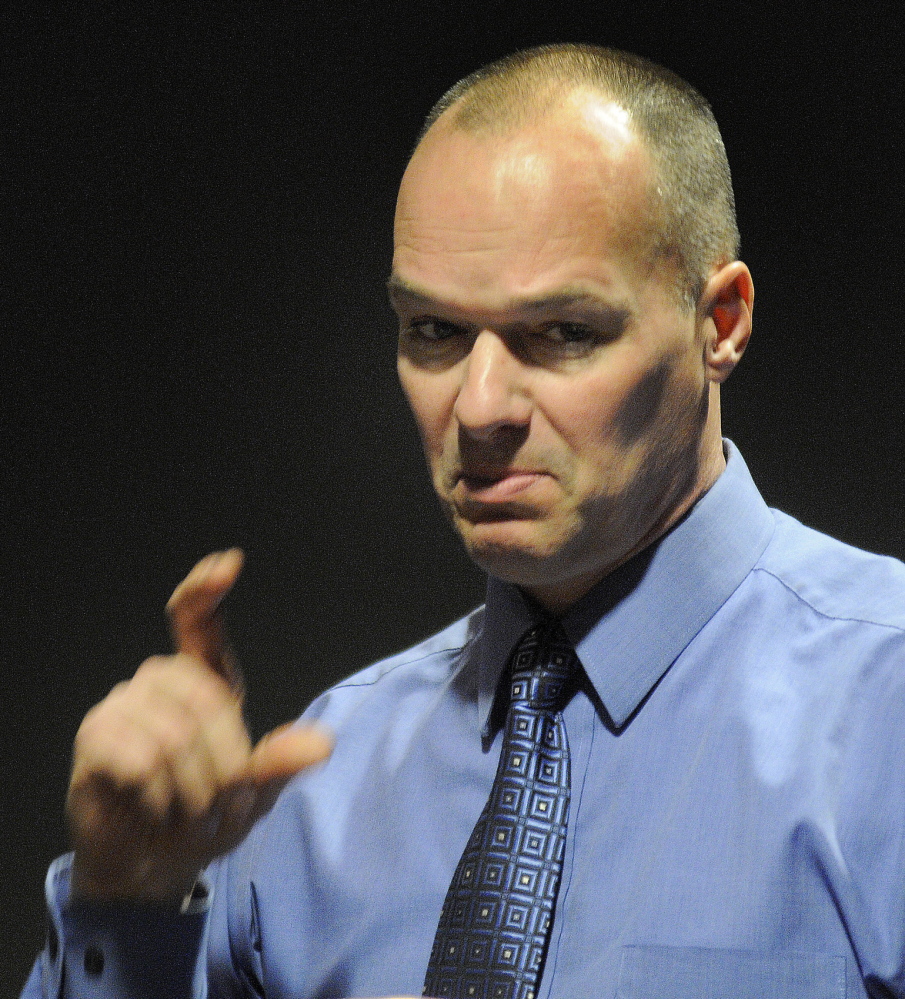

When Kennebec County Sheriff Randall Liberty was an Army drill sergeant, it was his job to ensure that new soldiers developed those traits. Sometimes that involved yelling at homesick teenagers.

After dealing with his own post-traumatic stress and seeing the effects of combat trauma on people in the criminal justice system, Liberty has come to appreciate that the coping mechanisms that help troops get through war can become harmful once back at home.

“It serves us well in combat — âfollow me and away we go,'” Liberty said. “You can’t think about it or feel too much. But when you get out, it all comes back.”

In a discussion Sunday at the Holocaust and Human Rights Center of Maine, Liberty talked about the treatment that helped him and what he’s doing to try to help other veterans.

The event included a screening of “A Matter of Duty: The Continuing War Against PTSD,” the Maine Public Broadcasting Network documentary about the veterans block Liberty has created at the Kennebec County jail and the Veterans Treatment Court overseen by Justice Nancy Mills in Kennebec County Superior Court.

The documentary includes interviews with Liberty about the anger problems he experienced after serving in Iraq in 2004 and with inmates in the veterans treatment program, who talk about the substance abuse that resulted from their traumatic experiences and the crimes it led them to commit, including robbery and operating under the influence.

Augusta resident Carol Aft thanked Liberty for addressing the problem of post-traumatic stress disorder, which is not new. It also affected people who served at the same time as her father, a veteran of World War II and the Korean War.

“At that time, the veterans came back, and they were experiencing the same thing. It was extreme stress, but there wasn’t a name for whatever it was,” Aft said. “Now that it’s being talked about and there’s programs in place to help veterans, essentially what you’re doing is helping to not throw away these young men in our society.”

Charles Gilbertson, a Navy veteran from Bath, said he thinks the documentary can be helpful to veterans’ family members, who might be able to recognize the behavior and emotions the subjects of the film describe. Spouses or relatives might notice the problem before the veteran is able or willing to, Gilbertson said.

Marjorie Dearborn, of Mount Vernon, said hearing the veterans’ stories made her think of a statement by the late South African leader Nelson Mandela, that hatred is something that must be learned because love comes more naturally to the human heart.

“That’s what everybody has to do again, to learn to get rid of their hate, whether it’s hate for the enemy or hate for what they’ve done or what they’ve seen,” Dearborn said. “They’ve got to get rid of their hate and let that natural love come back into their lives.”

Liberty said one thing that was upsetting about the Iraq War was that American soldiers didn’t hate Iraqis and in fact served alongside Iraqi soldiers, yet they ended up killing people who just wanted to protect their families. And the point of all the death and destruction was unclear, he said.

Two Iraq veterans became the first graduates of the veterans court in September.

There are about 100 such courts nationwide, but Kennebec County’s is the only one in Maine. The Legislature is considering a bill sponsored by Rep. Lori Fowle, D-Vassalboro, that would fund three new judges and several other court employees to create statewide access to veterans courts. The cost is estimated at $1.16 million.

Susan McMillan — 621-5645smcmillan@centralmaine.comTwitter: @s_e_mcmillan

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story