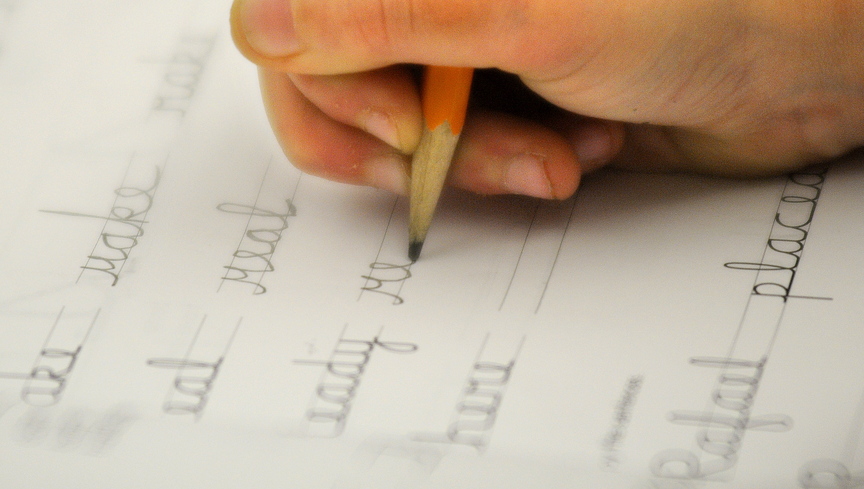

CHELSEA — It was “r” day in Rhonda Rush’s third-grade class.

Rush led her class through the cursive letter. The pencil stroke travels up to kiss the top line, then down slightly and back up, forming a little “smile,” as the workbook calls it, then back down to the bottom line.

The students copied a series of words that added “r” to the letters they’d already learned: race, are, after, their, rake, real, ready, there.

“Guys, be careful with your smiles,” Rush said. “Don’t make them come down too far, or your âr’s will look like âm’s.”

After finishing two pages in the workbook, students shook the cramps from their hands, then switched back to writing in print for the rest of the day’s work.

Because of technology and changing mandates, many schools have reduced or even eliminated the teaching of cursive handwriting. But Chelsea Elementary’s school district, Regional School Unit 12, made a new investment this year, purchasing a curriculum called Handwriting Without Tears that includes daily cursive lessons for third-graders.

Rush’s student Chloe Smiley said she wants to learn cursive so she can show adults what she can do when they quiz her about it.

“Whenever they’re like, âCan you spell my name in cursive?’ I’m like, âI’m sorry, I haven’t learned cursive yet,'” she said.

Chelsea resident Jessica Canwell said she’s glad her daughter, Jolie, is learning cursive in Rush’s class.

“Everybody has their own writing style, and not having cursive is losing something to the same-old, same-old,” Canwell said. “The personality of writing is being lost to computers.”

Canwell said she uses cursive when she writes manually, but most of the time she’s typing, both in her work as a bookkeeper and in her personal life.

Parents such as Canwell who want their children to learn cursive have their wish for now, for the most part. A survey of 612 elementary school teachers by teaching supplies retailer Really Good Stuff last spring found that 65 percent of second-grade teachers and 79 percent of third-grade teachersstill offer cursive writing instruction.

Many school officials, however, are reconsidering whether cursive is necessary, when writing on computers is so common in schools and workplaces. Cursive is not required in the curriculum standards that 45 states have adopted for English and language arts.

“I now prefer technology, but I still take notes, I still make lists, I still write things out, and cursive is the way I go. But I will admit, I’m of a different generation,” said Leanne Condon, assistant superintendent and curriculum director for Mt. Blue Regional School District, RSU 9. “Trying to understand what this generation needs is our task at this point.”

Condon said administrators in the Farmington-based school district will poll teachers for their thoughts about cursive and watch what districts in Maine and across the country are doing.

Handwriting is not mentioned explicitly in the Common Core State Standards that Maine and most other states are implementing. The standards state that students should write in every grade and require them to be able to type one page in a single sitting by the end of fourth grade.

Some states using the Common Core have added a standard for cursive handwriting or passed separate legislation to ensure that it’s still taught. Those states include California, Massachusetts and North Carolina.

Cursive was not required in the standards that the Common Core supplanted in Maine. The 2007 Maine Learning Results say that students at every level should be able to “create legible final drafts,” without specifying how.

Donna Madore, assistant superintendent of Augusta Public Schools, said students in the district learn cursive in third grade and may spend some additional time on it in fourth grade, but the subject is being squeezed out by other requirements.

“I think literacy instruction and math instruction and the content is all-consuming in our educational day, along with the social and emotional stuff that we have to help our students work through, and something’s got to give,” Madore said. “What has taken some of the time, as well, is teaching kids how to type.”

School officials said cursive still has some practical applications, such as being able to sign documents or copying the paragraph on the SAT promising not to cheat, which is not supposed to be written in print.

It may have some academic benefits as well. Rush said her experience as an elementary school teacher comports with research findings that learning cursive helps students write more quickly, smoothly and coherently.

Condon said teachers at Mt. Blue High School have found that when students accustomed to writing in cursive use it for timed writing assignments, they’re able to write more before time runs out.

Using cursive also may provide a slight boost on the SAT. The first year an essay was required as part of the SAT, 2005-06, the College Board found that students who wrote in cursive — who made up only 15 percent of test-takers — scored about 3 percent higher on that portion of the test.

Condon said it’s also a subject that many students enjoy.

“My third-grader right now is learning cursive, and it’s almost that rite of passage,” Condon said. “She comes home and sort of flaunts it to her brother: âLook, I know how to do this.'”

Linda Laughlin, assistant superintendent and curriculum director for Oakland-based RSU 18, said it might make more sense to teach students only as much cursive as is needed for the most important tasks.

“There is a need somewhere along the line for kids to actually be able to read it,” Laughlin said. “If you think about studying historical documents, they need to be able to read cursive.”

Learning to read cursive is fairly easy, Laughlin said, and doesn’t require learning to write it, which takes hours.

In the proficiency-based education model RSU 18 is putting into place, students are supposed to be able to demonstrate proficiency in every skill or concept that’s deemed essential, and Laughlin said writing in cursive did not make the cut as an essential skill in the curriculum.

Some teachers have dropped cursive as a result, Laughlin said, but many others still teach it.

“It’s one of those optional topics,” she said. “What I think a lot of teachers are telling me is that kids are pretty motivated to want to be able to do it, so they show them how to do it to some degree, but they don’t hold them to a proficient level of that skill itself.”

Susan McMillan — 621-5645 smcmillan@centralmaine.com Twitter: @s_e_mcmillan

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story