AUGUSTA — How did Christoper Knight end up in a Co-Occurring Disorders Court, where defendants usually carry a dual diagnosis of substance abuse and mental health disorders?

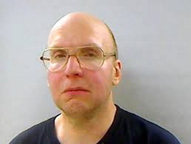

It was the best fit to reintegrate Knight, 47, dubbed the North Pond Hermit, into society say people who agreed to place him there.

“We’ll take a mental health diagnosis and a substance abuse problem or just a mental health diagnosis,” said Superior Court Justice Nancy Mills, who presides over the Co-Occurring Disorders Court. “If it’s just a substance abuse problem, the defendant could probably qualify for one of the drug courts.”

Knight spent the past 27 years living in the central Maine woods around Little North and North ponds in Rome and Smithfield, avoiding contact with people and making night forays into usually unoccupied camps to steal everything he needed to survive. His story gained national notoriety.

“Co-Occurring Disorders Court is the best place for people transitioning,” said Kennebec County Sheriff Randall Liberty. “We had a good consensus that this was the best scenario for him. This was a unique situation. It probably was a looser fit (than other defendants in the court), but it was the best safety net we could provide him with existing resources. Everybody just wants this gentlemen to transition well and succeed.”

Liberty’s jail has held Knight since April 4. That’s when he was arrested as he was leaving the dining hall of Pine Tree Camp in Rome with a backpack and duffel bag crammed with food and other goods. It was the third time in a year that Knight had burglarized the camp for children and adults with disabilities.

Last week, Knight pleaded guilty to those burglaries and thefts as well as to burglarizing three private seasonal camps, one of them in Somerset County, over the past six years.

Those crimes were a small fraction of the thousand burglaries and thefts he estimated he committed over the almost three decades since he left his family’s Albion home for his solitary existence. He told authorities he spent his time reading books, camouflaging his camps and listening to battery-powered radios. Knight had no contact with his family until they visited him in jail.

Knight’s attorney, Walter McKee, said that Knight underwent — at McKee’s request — a complete evaluation by the State Forensic Service, which assesses defendants for the court. “That identified significant mental health problems,” McKee said. “And there was evidence he’d been stealing alcohol and consuming it over some period of time.” McKee wouldn’t specify the mental health diagnosis.

At last week’s hearing in Kennebec County Superior Court, where Knight was admitted to the specialty court after his guilty pleas, there was no mention of those problems, but the alcohol issue was already public.

“We discussed ahead of time what we were going to put before the public,” Maloney said shortly after the hearing.

Knight said little at his hearing except to respond to questions from Mills about whether he understood his rights and the consequences of his guilty pleas. When she asked if he wanted to address the court, he declined.

McKee later described Knight as “withdrawn, consistent with living in the woods for 27 years.”

“There’s no clear indication of why he decided to stay living in the woods for 27 years,” he said.

Close monitoring

Weekly meetings of the Co-Occurring Disorders Court and the more frequent contact with members of the court team, some of whom make unannounced checks to make sure defendants comply with curfews as well as random drug screening, help ensure compliance and make problems clear almost immediately.

“Short of an ankle bracelet, you’re not going to get anybody more closely monitored,” McKee said. He has had previous defendants complete the Co-Occurring Disorders Court program, including a man who was convicted of robbing a pharmacy.

McKee said he fully expects Knight to succeed in the court program. “I’ll be there for sentencing and graduation,” McKee said.

McKee credited District Attorney Maeghan Maloney for “thinking outside the box” and working to get Knight into the program.

Maloney said those admitted to the court can have either a mental health diagnosis or a substance abuse problems although preference is given to those who have a combination. “If the team thinks they can help someone, they will,” Maloney said. “We always make room for people we think we can help.”

The court program uses a team approach, with the team headed by Mills, who can veto admittance.

“She truly is one of the most compassionate human beings,” Maloney said. “She is a big reason we’ve had so much success. People in the court know she honestly believes in them and is rooting for them.”

Team members — several of whom were introduced to Knight at the conclusion of last week’s hearing — include three case managers from Maine Pretrial Services plus director Elizabeth Simoni, the district attorney and/or assistant district attorney; Ashley Gaboury, a probation officer with the Maine Department of Corrections; attorney Seth Levy, who represents the defense bar; Hartwell Dowling, specialty courts and grants coordinator for the Administrative Office of the Courts; Anne Archibald from the Department of Veterans Affairs; Bob Kingman, who works with the Criminogenic Addiction Recovery Academy, which operates in the Kennebec County jail; and Roxanne Dimarco, a clerk in Kennebec County Superior Court. The case workers report to the judge on the defendants’ compliance as well.

The Co-Occurring Disorders Court was founded in 2005, and the veterans court in 2011.

Admission to the court — where the defendants plead guilty to crimes and are given the sentences under both the best-case and worst-case scenarios — is public, as are the final hearings when the sentence is imposed. However, the weekly meetings with the judge and the team are private.

Mills said those sessions include discussions of mental health and substance abuse problems, which federal legislation indicates should be closed. On the other hand, she said, “The legal aspects are not confidential.”

‘They need our help’

Mills, who founded the Co-Occurring Disorders Court, has been open to accepting defendants charged with varying crimes into the program, and particularly those who are veterans.

“They need our help,” Mills said. “They have very significant challenges, and you just can’t punish them by incarceration and have them come out with no changes.”

She said she had been reviewing the list of crimes committed by those who have participated in the Co-Occurring Disorders Court. “It really hits every class A felony there is,” Mills said, differentiating it from misdemeanor courts and traffic courts elsewhere in the United States.

“We will consider any crime,” she said. “We obviously couldn’t consider murder because the up-front minimum mandatory sentence is 25 years.”

She said 13 veterans are enrolled in the veterans court portion, with three more people pending a decision to come in.

“Our goal is have 25 veterans at least,” she said. About a dozen other people are in the Co-Occurring Disorders Court itself. Mills said some people have referred to the requirements of Co-Occurring Disorders Court as “probation on steroids.”

Knight’s conditions, for instance, require him to:

– report to the judge and the court team on Mondays at Kennebec County Superior Court;answer questions truthfully;

– follow a treatment plan set up by his providers;

– comply with pharmacy conditions;

– stay away from alcohol and illegal drugs and nonprescribed drugs, including K-2, Spice and synthetic cannabinoids;

– comply with random testing for drugs and alcohol and avoid contact with drug users;

– avoid criminal activity and tell the team members of any contact with law enforcement;

– get his case manager’s approval to leave the state;

– live in a court-approved location and adhere to a 8:30 p.m.-6 a.m. curfew, subject to bail checks;

– have no contact with the victims of the crimes charged, including Pine Tree Camp;

– seek a job or enroll in school;

– have no have dangerous weapons or firearms and not be in a location where alcohol is served on premises.

While Knight remains in jail, program compliance is easier. There is no curfew to worry about and no missed meetings because he will be brought to the court each Monday by officers of the Kennebec County Sheriff’s Office. But he should be released to a pre-approved housing arrangement in the next month or so.

“The philosophy of the court is to have the person be in the community as soon as possible,” Maloney said. “It’s a lot harder to be successful when they’re on the outside.”

Maloney said that while the supervision is intensive, “I still think it’s less expensive than prison.” Maloney cited 2012 figures from the Vera Institute of Justice showing that incarceration cost Maine taxpayers $46,404 per inmate annually. In 2011, former District Attorney Evert Fowle said the Co-Occurring Disorders Court program spends about $6,000 on each client in the program.

Under the plea agreement, if Knight successfully completes the program — which requires a minimum of one year and can be more than two years — he will be sentenced to five years in prison, with all but seven months suspended, and three years’ probation with the following conditions:

– participate in a restorative justice conference;

– follow all Co-Occurring Disorders/Veterans Court after-care recommendations;

– have no alcohol, illegal drugs, weapons or firearms, and be subject to random search for those;

– undergo substance abuse and psychological counseling;

– pay restitution of at least $1,894.75 to the victims of charged and uncharged cases within the statute of limitations;

– forfeit $457.70 and $100 in pesos which police found on him and at camp in the woods in Rome;

– have no contact with victims except at court-approved activities.

If Knight fails and is dismissed from the Co-Occurring Disorders Court, his sentence is capped at seven years in prison or seven years in prison with all but four years suspended and two years’ probation that include the above conditions.

Betty Adams — 621-5631badams@centralmaine.comTwitter: @betadams

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story