When House Majority Leader Eric Cantor rolled out a list of Republican demands this week for raising the federal debt limit, there was a surprising omission: any real plan to tackle the debt.

Republicans have long vowed to use the threat of default to force Democrats to confront the soaring cost of caring for an aging population, the nation’s central budget problem. Instead, Cantor, R-Va., revealed more limited ambitions: Delay the implementation of President Obama’s health-care law for a year. Promote tax reform. Build the Keystone XL oil pipeline.

Democrats, for their part, have largely stopped talking about imposing new taxes on the rich and are focused on reversing sharp spending cuts known as the sequester. As Washington slouches toward the next battle in its three-year budget war, both parties have abandoned the quest for a “grand bargain.” Instead, with a shutdown set to occur in 11 days unless a deal is reached, lawmakers are aiming mainly just to keep the lights on and not miss a payment on the bills.

“It’s total atrophy. We’re earning our 11 percent popularity” rating, said Sen. Johnny Isakson, R-Ga., the leader of the latest group of lawmakers to try to forge a big debt deal. “It’s easier to talk about Obamacare than the major sources of our problems.”

A TALL ORDER

Meeting even the modest goals of routine governance could prove to be a tall order this time around. On Thursday, Obama made plans to talk with congressional leaders next week, the White House said. Meanwhile, House Republicans were preparing for a Friday vote on a plan to fund federal agencies through Dec. 15 but defund the health-care law — a proposal even many senior Republicans were calling doomed.

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., vowed to strip out the anti-Affordable Care Act provisions and send a plain government funding bill back to the House, saying that “any bill that defunds Obamacare is dead. Dead. It’s a waste of time.”

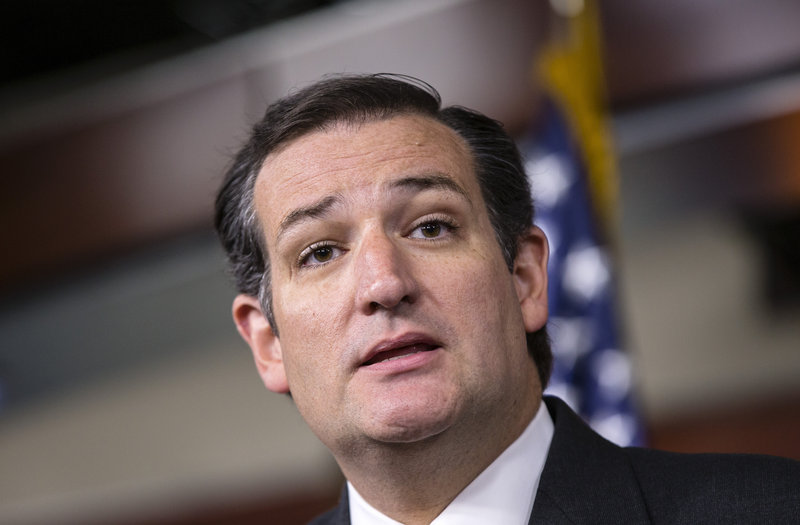

Republicans, including Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, the health-care law’s chief antagonist in the Senate, acknowledged that they have few procedural tools to block Reid’s maneuver. Even if the Republicans filibuster the bill, Democrats say they have the votes to return it to the House by the end of next week.

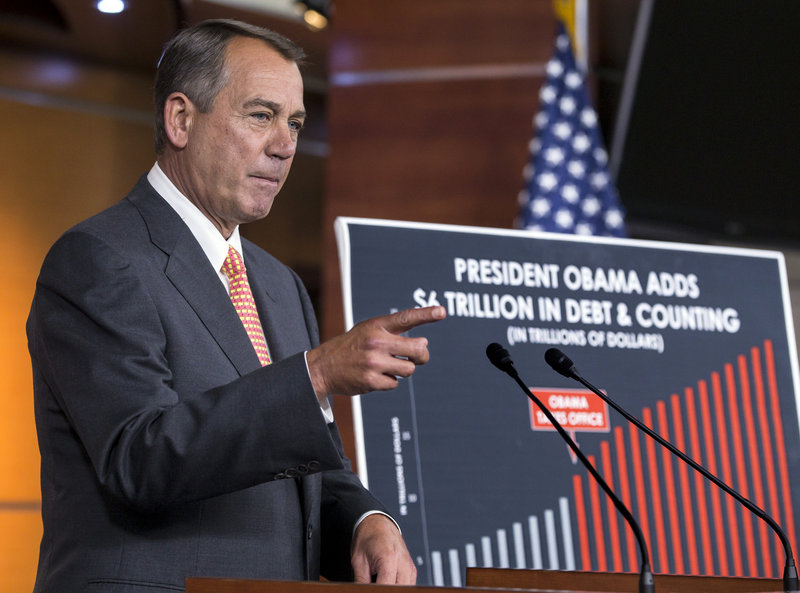

Cruz’s concession infuriated House Republicans, including Speaker John Boehner of Ohio, who called on Cruz and his Senate allies Thursday “to pick up the mantle and get the job done.” Meanwhile, Boehner and his team were hatching a plan to rework whatever comes back from the Senate, push a new bill through the House and demand that the Senate vote again — a strategy that would increase the odds of a shutdown on Oct. 1.

Among the ideas under consideration: Tack on an amendment that would take away benefits for members of Congress who participate in the health care law’s insurance exchanges. The hope is that lawmakers in both parties would rather lose those individual subsidies — worth about $5,000 to $11,000 annually — than let the government shut down. But it’s unclear how that largely symbolic gesture would further the cause of undermining the Affordable Care Act.

Regardless of whether they manage to keep the government open, lawmakers will face their next major deadline in late October. That’s when analysts say the Treasury Department is likely to run short of cash to pay its bills unless Congress raises the $16.7 trillion federal debt limit.

House Republicans expect to vote as soon as next week to give Treasury enough borrowing authority to get through the 2014 midterm elections. In return, Cantor said, they will shoot for a grab bag of modest trophies, including approval of the Keystone pipeline, a timetable for tax reform, and “a variety of other measures designed to lower energy prices, simplify our tax system and get our economy going.”

Republicans could provide no details about any of those proposals.

“It’s to be determined, really,” Rep. Patrick Tiberi of Ohio said as he emerged from a meeting to flesh out the evolving measure.

Although Cantor didn’t mention it, senior Republicans said they also are considering small cuts to federal entitlement programs, such as a provision to require wealthy seniors to pay more for Medicare.

But they have ruled out larger reforms, such as Obama’s proposal to use a less-generous measure of inflation to calculate Social Security cost-of-living adjustments, an unpopular idea that until recently ranked at the top of their list of demands. And even the Medicare change may not make it into the final bill.

“The speaker has said and others have said we would really like to do entitlement reform,” Tiberi said. But the debt-limit bill “may not be the vehicle.”

Republicans blamed the White House for their lack of ambition. The last time there was any talk of a broad deficit deal, Obama proposed a package worth $1.6 trillion over the next decade. It included the Social Security inflation adjustment and $400 billion in cuts to Medicare and other health programs — serious proposals, in Republicans’ eyes.

But in return, Obama wanted about $600 billion in new taxes, on top of tax increases enacted during the year-end fight over the “fiscal cliff.” Worse, Republicans said, he wanted most of the money to replace the sequester cuts, leaving barely enough new savings to cover this year’s deficit of about $650 billion.

Isakson and seven other Senate Republicans met with the White House during the spring and summer to try to bridge the divide between the Republican desire for more significant Medicare reforms and Obama’s desire for higher taxes. Last month, they called it quits.

Sen. Bob Corker, R-Tenn., a member of the group, said there are no plans to start again.

“It’s over,” he said Thursday. “We gave some very specific proposals to the White House, but … I don’t really think there’s desire over there right now to really tackle this issue. They see deficits coming down, they see the House in disarray, and I don’t think they feel [a big debt-reduction deal] is necessary right now.”

Democrats, meanwhile, blamed Republicans for refusing to consider higher taxes at a time when the aging baby-boom generation is straining federal resources.

“The president has tried. He spent more money on private dinner parties with members of the House and Senate over the last 10 months, saying, ‘If you want to engage in this conversation, let’s sit down and do it.’ No takers,” said Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill., a member of the Bowles-Simpson debt-reduction commission.

ARE DEAL-CUTTING EFFORTS DONE?

Does that mean efforts to cut a far-reaching deal are done? “Sounds like it,” Durbin said. “At least for now.”

This week, a Congressional Budget Office report showed that the problem is far from over. The debt is larger, as a percentage of the economy, than at any time in U.S. history except World War II. Although annual deficits are shrinking fast, they are expected to start rising again in 2016 and to keep growing as the baby-boom generation retires.

Over the next 25 years, projections show the debt approaching WWII levels, with no chance of an armistice to bring relief. The CBO said policymakers need to find about $350 billion a year in fresh savings to bring the debt back down to pre-recession levels.

Pockets of hope for a long-term deal linger on Capitol Hill, mainly around the push for an overhaul of the tax code. “Maybe tax reform is going to give us the opportunity to re-establish these conversations,” said Sen. Michael Bennet, D-Colo., a member of the tax-writing Senate Finance Committee.

But tax reform won’t happen fast. In the meantime, “this somehow has shifted away from a debt-and-deficit conversation into a defunding-Obamacare conversation,” Bennet said. “Which doesn’t really suggest there’s going to be a way to get to any larger deal.”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story