When Mike Lyons was in a car accident in 2008, he knew right away that his shattered body would never recover fully. What he didn’t realize was that his finances would be ravaged as well — the driver who hit him was one of an estimated 42,000 in the state who don’t carry vehicle insurance.

Lyons, 60, of Vassalboro, who works in marketing for Bank of America, was driving north to work on U.S. Route 201 in Winslow on a Saturday morning when a woman driving in the opposite direction made a left turn in front of him.

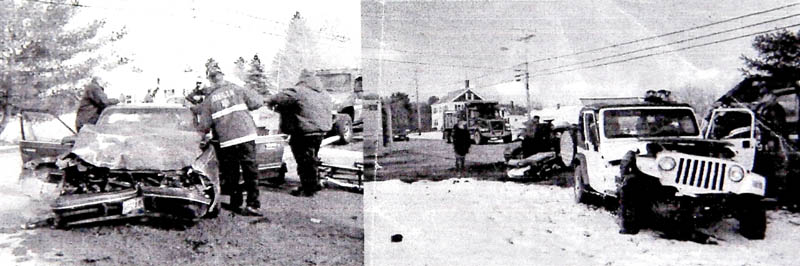

Their cars collided.

The impact threw Lyons forward with such force that the metal pin holding his seat belt snapped. His head cracked the windshield and he had deep cuts to his ankle and hand.

His right knee, which had been braced against the dashboard, was smashed, and his femur broken in five places.

It took emergency responders more than an hour to get him out of the twisted wreckage. His wife, who rushed to the scene, quoted him in her journal.

“Please don’t let me die,” he said, over and over. “I don’t want to die today.”

In the immediate aftermath of the accident, which began with a 6 1/2 -hour stretch on the operating table at Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor, the Lyonses were focused on his pain and the path to recovery.

However, in the crush of information surrounding Lyons’ medical condition — a world of vomiting, bowel obstructions, nose tubes, medical scans and a huge amount of pain — there was one detail that would gain increasing importance.

The driver who was at fault in the accident carried no vehicle insurance and had no assets, which meant that Lyons would suffer not only the medical consequences of the crash, but the financial ones as well.

The number of uninsured drivers on Maine’s roads, and the risk that they carry with them, is huge.

Of Maine’s 930,000 licensed drivers, about 42,000 don’t have insurance — about one for every 22 drivers in the state, according the Insurance Research Council, an independent nonprofit research organization supported by national insurance companies. It does not advocate about public policy or seek to influence legislation directly, according to its website.

The risk rises during Labor Day weekend, when 1.7 million New Englanders, about 12 percent of the region’s population, travel 50 miles or more from home, according to AAA Northern New England.

In Maine, drivers are required to carry at least $50,000 in insurance coverage.

During traffic stops, police officers routinely ask for proof of insurance. Last year, 3,614 drivers in Maine were convicted of failing to provide proof they had coverage at the time they were stopped within the 20 days required, according to the Bureau of Motor Vehicles. Failure to provide proof of insurance carries a hefty fine — frequently larger than the fine for violation the driver was stopped for — and a license suspension.

The state also requires that drivers provide proof in order to register a vehicle.

Maine’s rate of uninsured drivers is better than those of other states — among the lowest in the nation — but that’s small comfort to the drivers who are injured each year in accidents with uninsured drivers — about 225 a year, according to the Maine State Police.

Lack of coverage

Attorneys familiar with personal injury cases said people drive without insurance for a variety of reasons.

Some have no license and are therefore uninsurable. Others have let it lapse.

Jason Jabar, an attorney with the Waterville-based firm Jabar, Bettern, Ringer & LaLiberty, said economics often plays a role.

“We don’t live in a community where people have a lot of disposable income,” Jabar said.

The research council supports that, citing the recession as the cause for a national increase in uninsured drivers in 2008.

If people are under financial stress, insurance bills aren’t as high a priority as grocery, rent or utility bills, which pay for immediate and continual needs.

Insurance becomes a priority only for those who own a house or car, Jabar said.

“If someone has assets, it’s in their interest to be insured to protect those assets,” he said.

This often results in added bad news for the victims of an accident involving an uninsured driver. If the driver carried no insurance, it’s less likely that any property will be available to be taken for compensation for medical bills.

“Except in a very rare situation, the individual is not going to have the assets to cover the damages,” Jabar said.

In one case, he won a $400,000 judgment against a driver who caused permanent injuries to his client.

“The driver he got a judgment against just filed for bankruptcy,” he said. “We were never going to be able to collect anyway.”

Karen Boston, a personal injury lawyer at Lipman & Katz, an Augusta-based firm, said victims are often left holding the bag.

“It can result in very unjust situations,” she said.

Boston and Jabar both said the state minimum of $50,000 in insurance coverage is often not enough to cover the medical expenses that come with a serious accident, but that some coverage is better than none.

No money, permanent harm

Jabar said crash injuries cause permanent harm — to avid hunters who can’t hunt anymore, or parents who no longer can care adequately for their children — to victims who can’t have the quality of life they once led.

“It’s hard to really understand what it’s like until you or someone you’re close to goes through that,” he said.

When money can be tapped to pay for an accident’s effects, federal law ensures the medical providers are first in line, resulting in what Jabar called “pass-through compensation.”

Lyons said watching his own insurance money pass through his possession to pay off his medical bills was frustrating.

“I had a check in my hand for $100,000 and I had to sign it over,” he said.

While he knows the bills are important, he said, there are other expenses associated with the accident that are equally important. The loss of his job and income, four years of pain medication, the stress, the loss of his vehicle, the time and travel expenses — are all borne by him and his wife.

“The accident was just the tip of the iceberg,” he said.

Lyons, 65, still suffers the effects of the accident five years ago.

He can’t work, which has cut the household income in half.

He used to enjoy traveling, but he fell when walking because the accident left one leg 1 1/2 inches shorter than the other. The lacerations caused by the accidents and the surgeries have healed but left scars. When he snapped the seat belt with his body, it injured his internal organs, resulting in continued problems with his bowels. In all, he has undergone nine surgeries in an attempt to repair the damage.

Accountability

Lyons would like tougher penalties for those who drive without insurance. When a police officer finds an uninsured driver, he said, the driver shouldn’t be allowed to continue down the road. Lyons would like the vehicle impounded unless it can be driven legally with insurance.

Jabar said the idea makes sense to him.

“I don’t see the downside,” he said. “If somebody’s vehicle is uninsured, then it really shouldn’t be driven.”

Lyons raised the idea during a public meeting with Gov. Paul LePage, who Lyons said, expressed interest.

LePage’s spokeswoman, Adrienne Bennett, confirmed that the two met, but did not respond to inquiries about LePage’s position on the issue.

After Lyons sent a follow-up email to LePage, Lt. Brian Scott, commanding officer of the traffic safety unit of the Maine State Police, responded to Lyons on LePage’s behalf.

In the response, Scott cited the thousands of tickets issued to uninsured drivers every year, and said the purpose was to hold violators accountable.

Lyons said more needs to be done to protect those who, like him, are caught between an uninsured driver and massive medical bills.

Lyons’ situation has improved. After years of searching, he found a doctor who agreed to replace his hip, which has helped him walk and eliminated his physical pain.

However, Lyons is still angry — with the system and with the uninsured driver who wreaked havoc on his life.

He’s angry that he has been left with such a heavy burden through no fault of his own.

For each consequence he suffers, he can’t help but draw comparisons.

After he was classified as disabled, he said, “I had to go down to the registry and do a driving test. I’m the one that had to take the driving test.”

Lyons said he won’t feel better until the risk posed by uninsured drivers is eliminated for those who are put in a no-win situation simply for venturing onto the road.

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling — 861-9287

mhhetling@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story