NEW YORK — Like the famous marble lions out front, the New York Public Library’s flagship building has long symbolized serene endurance in the service of knowledge. But plans for a major change within the landmark have kindled an intellectual culture clash over its direction and the future of libraries themselves.

The $300 million-plus proposal entails moving millions of books out of the Fifth Avenue building’s storied research stacks and into storage to make way for a lending library with other volumes, computers and a cafe.

Library officials say it will save the research books and millions of dollars and adapt the grand building further to the wired world. But a roster of scholars, preservationists and other critics suspect the library of masking a real estate ploy as a public benefit and say the project will turn a singular institution into “library lite.”

Bibliophiles protested outside a trustees’ meeting, Pulitzer Prize-winning historians have sued the library, and novelists including Salman Rushdie, Jonathan Lethem and Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa signed a petition. While library leaders have made sizable concessions and say the plans are being redrawn, the uproar continues in a chorus of anxieties about libraries’ roles when information is only a touchscreen away.

For libraries in general, “this is a moment of transformation,” library President Anthony Marx said in an interview. “And certainly the controversy over this building and its renovation is, I suppose, the most visible aspect of that transformation.”

In recent years, many libraries have grappled to balance — and pay for — new demands for electronic services and livelier environments against their commitments to provide repositories for books and settings for study. Their efforts have spurred commentary about the line between catering to changing times and morphing into a book-themed mall.

Those choices have come under scrutiny in cities including Seattle, where the striking, 9-year-old Central Library has been praised as a design jewel, tourist draw and boon to book circulation but faulted as short on amenable spots to, well, read. After San Francisco’s new main library opened in 1996, novelist Nicholson Baker publicly deplored plans — ultimately abandoned — to eliminate its card catalog in favor of an online system.

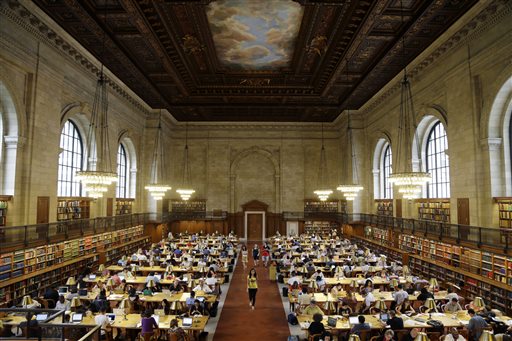

But perhaps no other U.S. library has the profile of the New York Public’s 102-year-old main building. Scenes from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and “Network” were filmed there. More than 100 books have been at least partly researched or written there, including Robert Caro’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Power Broker” and Karen Russell’s acclaimed 2011 novel “Swamplandia!”

The building draws up to 2 million people a year. Any of them can request a book from the research collection, and 4 million of those volumes have been in the stacks, available for perusal in generally about 15 minutes.

Under the overhaul plan, about 1 million or more of those books would go permanently to a repository in New Jersey; the library would aim to fill requests within a day but acknowledges it sometimes can’t now. Initial plans called for sending the entire research collection there, but the controversy prompted an $8 million donation to put at least 3 million volumes in an existing underground book storage adjoining the library.

In place of the staff-only stacks would be an airy space where visitors could browse and borrow from a collection of more than 500,000 books, moved in from the Mid-Manhattan Library across the street and a science and business library about half a mile away. Their spaces would be sold to generate an estimated $200 million; the city doesn’t run the library but has pledged another $150 million. Officials say the initial $300 million price tag is in flux, with a new design due in the fall.

Library officials say the project would get books out of stacks that don’t meet current preservation and fire-safety standards, create a better setting for the shopworn Mid-Manhattan Library’s roughly 1.5 million annual visitors, and generate more than $15 million a year in savings and income from investing the proceeds of the real estate sales.

And, Marx says, “we want the public to enjoy this building more.”

Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer Edmund Morris, a plaintiff in one of two lawsuits seeking to block the plan, says researchers accustomed to leapfrogging from one volume to another would be frustrated if they had to stop and wait for books.

For now, no changes are imminent. Amid the lawsuits, the library agreed last month not to do construction work on the stacks until at least mid-October.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story