WASHINGTON — Students applying for financial aid for the coming school year could find some comfort in a bipartisan student loan compromise taking shape in the Senate that would prevent interest rates from doubling and set a single rate each year for undergraduate students, rich or poor.

Interest rates, which would be tied to the financial markets, would rise slightly to 3.8 percent for low-income students receiving new subsidized Stafford loans this year but not double as they’re scheduled to do July 1. Despite the increase, the rate is still lower than the 6.8 percent students would face absent congressional action. The current rate is 3.4 percent.

More-affluent undergraduates would see a bigger decline; the interest rate on new unsubsidized loans would drop from 6.8 percent to 3.8 percent under current market conditions.

Rates for all new federal student loans would vary from year to year, according to the financial markets. But once students received a loan, the interest rate would be set for the life of that year’s loan.

Rates for parents and graduate students also would be tied to the markets.

A draft of the proposal was obtained Wednesday by The Associated Press.

Congress is grappling with student loans for the second straight year, with each party pointing fingers at the other about who would shoulder the blame if rates double. The House passed legislation that also ties rates to the markets but the Senate earlier this month voted down two competing proposals.

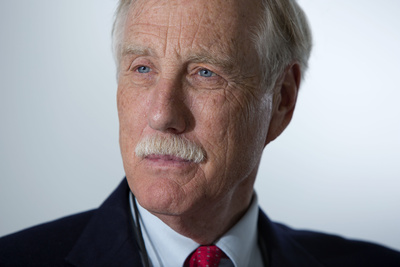

The latest Senate compromise, developed during conversations among Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, Republican Sen. Tom Coburn of Oklahoma and independent Sen. Angus King of Maine, was being passed among offices. None of them publicly committed to the plan until they heard back from the Congressional Budget Office about how much the proposal would cost.

A day earlier, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid told reporters negotiations were afoot and predicted a deal could be reached. He mentioned talking with Manchin and King, as well as Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Jack Reed of Rhode Island.

“The last 24 hours, I’ve spent hours working with interested senators,” Reid said Tuesday.

“We’re not there yet,” he added.

Education Secretary Arne Duncan and White House economic adviser Gene Sperling would have lunch with senators on Thursday, Reid said.

Republicans, meanwhile, have been unrelenting in their criticism of Democrats for opposing tenets of Obama’s student loan proposal, chiefly rates that change every year to reflect the markets. Without action, Republicans said, students were left not knowing how much they would be paying for classes this fall.

“It’s not fair to these students and not fair to students across the country who need to know what the cost of their loans is going to be and what the interest rate is going to be,” Republican House Speaker John Boehner told reporters.

Last year, Congress voted to keep interest rates on subsidized Stafford student loans at 3.4 percent for another year during a heated presidential campaign. Without the attention, education advocates worried that the interest rate would revert back to former rates on July 1, leading to extra out-of-pocket costs for students.

Six sometimes overlapping versions of student loan legislation were being considered in the House and Senate. Two bills – Senate Republicans’ and Senate Democrats’ proposals – both failed to win 60 votes needed to advance last week, seeming to suggest student loans were going to double.

Other proposals had champions among wings of their parties but only the House had passed student loan legislation that ties interest rates to Treasury notes. That bill drew a veto threat from the White House.

“The House has done its job. It’s time for the Senate to do theirs,” Boehner said.

It seemed work was afoot behind the scenes.

The bipartisan Senate proposal being circulated with just days to spare before interest rates increased borrowed pieces from the various suggestions.

In the potential compromise, interest rates would be linked to 10-year Treasury notes, plus an added percentage – just like Obama’s proposal, as well as those from House and Senate Republicans.

When students sign for loans each academic year, their interest rate would be locked in for the life of that year’s loan. For instance, students could wind up paying a higher interest rate for their sophomore year than their freshman year if the economy continues to improve and 10-year Treasury rates increase.

Students from lower-income families are eligible for subsidized Stafford loans, in which the government covers interest costs while they are in college. Those loans make up about a quarter of all federal student lending.

At the end of their studies, students could consolidate their loans, as is the case now. The current system caps that rate at 8.25 percent and lawmakers were considering keeping that in place.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story