The summer solstice is on June 21 this year. It’s the day when the sun reaches its highest point at midday and that has the longest interval of daylight. In my part of the world, there will be about 15 hours and 34 minutes (and some seconds) between sunrise and sunset.

But weirdly, it’s not the day of the earliest sunrise or latest sunset.

The word solstice comes down through antiquity from the Latin word solstitium, meaning the point at which the sun stands still. Sol means sun, and stitium is apparently a form of the verb sistatum, meaning to come to a stop.

Does the sun slow down and stop up there every June and December? Well, no, but it looks like it.

The Earth rotates once every 24 hours — approximately — creating day and night. Everybody knows this. The Earth also revolves around the sun once every 365 1/4 days — one year. If you were to track the stars over the course of the year, you would notice that they seem to make yet another big circle around us. And if you made a chart of the sun’s position in that circle, you would see that it seems to rise higher in its track through the sky from December to June, then descend lower from June to December.

But neither the sun nor the stars are actually moving like that. Their motions are illusions created by motions of the Earth. Like the telephone poles that seem to be rushing past when you’re driving on the highway, it’s your car that’s moving, not the telephone poles. The Earth is moving, not the stars and sun.

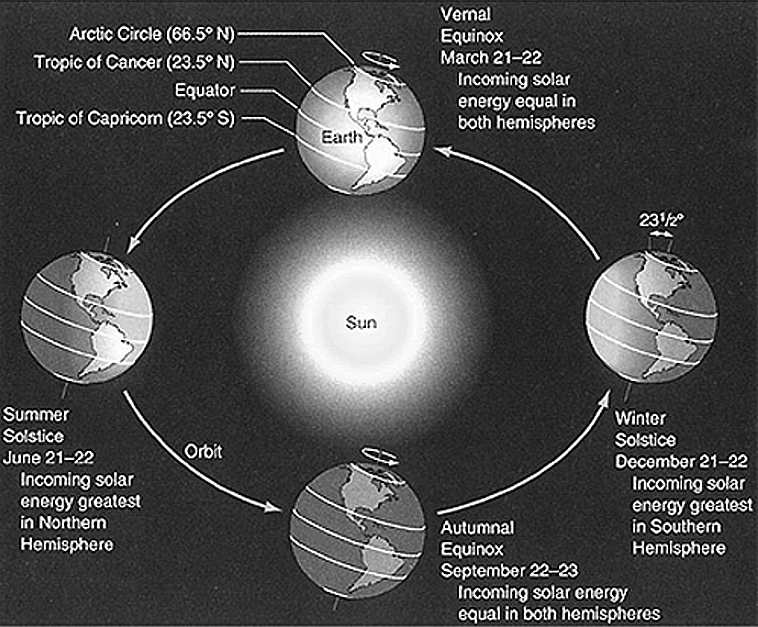

So the Earth is orbiting the sun. But the Earth also is tilted, which influences what that motion looks like to us. In other words, the North and South Poles are tipped at an angle (of about 23.5 degrees) with respect to the sun. In the part of the orbit when the North Pole is tipped toward the sun, the sun climbs higher and stays up longer, and we have summer. When the North Pole is tipped away, the sun is lower and the days are shorter, and we have winter (while the Southern Hemisphere has summer).

So this tilt, combined with the Earth’s orbital motion, changes the altitude of the sun — as we see it — over the course of the year. It reaches its highest point around June 21 each year, and its lowest point around Dec. 21.

Now common sense suggests that the longest day of the year would also be the day of the earliest sunrise and latest sunset. But common sense also suggests the sun is going around the Earth, which it’s not.

The earliest sunrises of the year actually happen in the weeks before the solstice. This year, in my part of the world (Troy), the sun rises about 4:51 a.m. June 10-20, according to the U.S. Naval Observatory. From June 19-26, sunrise is about a minute later, at 4:52. Similarly, the latest sunset is not on June 21, as you might expect (when it sets at 8:26 p.m.), but a few days later at about 8:27 June 24-27.

Why don’t the earliest sunrise and latest sunset coincide with the longest day of the year?

Well, three factors interact with each other to make the clock time of sunrises and sunsets a moving target.

1. The Earth rotates once a day, every 23 hours, 56 minutes and 4 seconds. Your clock, on the other hand, measures the day as 24 hours. So there is a nearly four-minute lag between one day as measured by your clock and one day as measured by the sun.

2. The Earth’s tilt on its axis means that every day, the position of the sun changes, northeasterly from December to June, or southwesterly from June to December, pushing sunrise and sunset times back and forth during the year.

3. The Earth’s orbit is not a circle; it’s an ellipse. Since the sun is not at the center of the orbit, but slightly off-center, the Earth is closer to the sun in winter months, and farther from the sun in the summer months. When it’s closer, it’s moving faster; when it’s farther away, it’s moving slower.

Each of these three factors creates its own discrepancy between the time measured on your clock, and the time measured on a sundial, which gauges the position of the sun. There’s a varying discrepancy between clock time and sundial time averaging out to about 15 minutes a year, pushing the times of sunrise and sunset off what you’d get in a straight-up-and-down, 24-hour, circular world.

At the solstices, the intricate tilt and whirls of the Earth create the illusion the sun is slowing down and changing direction. It’s easy to see why ancient people depicted these motions as a story of cosmic powers. If you ask me, it still looks that way, whether you understand what’s really moving, or not.

Dana Wilde lives in Troy. His writings on the stars and planets are collected in “Nebulae: A Backyard Cosmography,” available from Booklocker.com. Backyard Naturalist appears the second and fourth Thursdays each month. You can contact him at naturalist@dwildepress.net.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story