READFIELD — Sydney Green had a name from a headstone in France, some military records and a genealogy website just recently loaded with information from the 1940 U.S. Census.

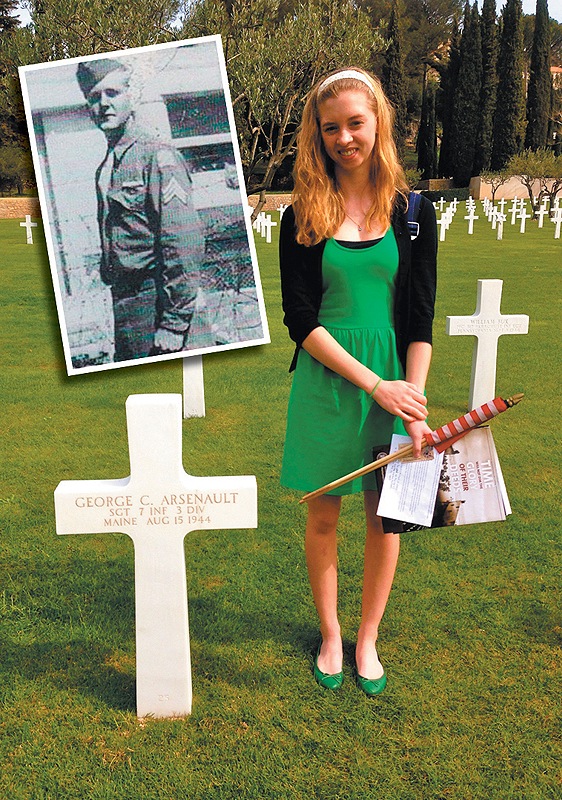

Now, thanks to sleuthing by the Maranacook Community High School sophomore, caretakers at the Rhone American Cemetery and Memorial have information about a Rumford soldier, Sgt. George C. Arsenault, to share with visitors.

Nearly 900 Americans are buried in the World War II cemetery in southern France. Seven of them were from Maine, as a group of Maranacook students learned when they visited on an exchange trip two years ago.

Green was one of several students who volunteered to research soldiers from Maine and elsewhere in New England in advance of another school trip to France this spring. She was the only one who succeeded in finding a living relative: a brother, Leo Arsenault, who’s 85 and still lives in Rumford.

“I was quite flabbergasted,” Leo Arsenault said in an interview. “After (69) years, somebody remembered him. It’s quite something.”

History teacher Shane Gower helped the students in their search, mainly through a school subscription to the genealogy site, Ancestry.com. Records from the 1940 Census had just been released last spring, but most of the students nonetheless struck out quickly.

Gower said the search for George Arsenault’s relatives immediately looked more promising. He’d been one of 15 siblings, and he fell in the middle of the pack, so it was possible some of the others were still alive.

Together, Gower and Green unearthed a sister’s obituary that named dozens of relatives, including a nephew in Winthrop. He wasn’t listed in the phone book, but Green thought to reach out to him through Facebook.

The man said yes, he had an uncle George who was killed in action in France. He gave them a phone number for another uncle, Leo Arsenault, who agreed to meet Green and Gower at Maranacook.

“The first thing he asked us is, ‘Why are you doing this? Why my brother?'” Gower said. “Sydney hadn’t really talked about it ahead of time, but she sort of kind of quickly responded that it’s important, it’s something meaningful and it’s an important thing to do. I think it made sense to him, and after that he gave us everything we wanted.”

Green said it was rewarding to have her research pay off, and Arsenault seemed to appreciate the effort.

“He was really happy that we were continuing the memory of his brother and continuing to show respect and show admiration for these soldiers who died for us,” she said.

Leo Arsenault allowed Green to scan letters his brother had sent home and photos of him with friends at basic training and in Naples, Italy, and then provide those to the Rhone cemetery staff.

George Arsenault left high school in the fall of 1943 to join the Army. As part of the 7th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division, he went first to North Africa, then fought at the Anzio beachhead in Italy and in the push to capture Rome.

In one of his letters home, Arsenault wrote about capturing a soldier in Italy. He had resolved to shoot the next Axis soldier he came across because they had killed his best friend, but he couldn’t bring himself to do it when he saw that the boy was even younger than himself.

His division was among the first Allied troops to enter Rome, Arsenault wrote, and they were greeted by cheering crowds. He had his first chance to shower, shave and change clothes in three weeks.

Eight days before he died, Arsenault wrote a letter to one of his sisters, asking her to have have his siblings pray for him as he prepared to lead a dozen men into the next campaign, and for her to notify two girls in town if anything happened to him.

Arsenault died on Aug. 15, 1944, the first day of the Allied invasion of southern France, known as Operation Dragoon. A fellow soldier told his family that he was killed by a land mine. He was 18 years old.

Leo Arsenault said his mother was offered the choice to have him buried in France or bring his body home to Rumford. The children persuaded her to to have him buried in a military cemetery because there was a better chance his service would be remembered and his grave maintained for generations to come.

Arsenault said he doesn’t remember much about his brother, except that he was very religious.

“It’s kind of hard for me because we were all real young when we left,” he said. “I was only 17 when I went in(to the Marines), and he was 17. I didn’t get to know him at all, hardly. He worked and went to school, and I worked and went to school.”

Several of the Arsenault siblings, including one sister who was a nurse, served in the military between World War II and the Vietnam War, representing every branch except the Coast Guard. Leo Arsenault was a Marine during World War II and the Korean War.

During the April vacation, Green and a group of Maranacook students visited the Rhone American Cemetery, where they learned about some of the troops buried there and read excerpts of George Arsenault’s letters aloud.

“For that to become real was really powerful, and hearing other stories from other soldiers and their families was really amazing as well,” Green said. “Hearing that this actual person went through all of these things that I’ve heard about in books and in stories was incredible.”

Gower said he reminded the students that many of the soldiers were just about their own age, and they sacrificed their opportunity to go to college and raise families to make the students’ lives possible today.

“It seems as though for many folks in France, it’s almost a bigger deal in many ways than it might be here in America, at least for people Sydney’s age,” Gower said. “Maybe the connection is stronger because it was their homeland, and the cemeteries are there, some of the scars are still there.”

Green and Arsenault will be recognized at the Regional School Unit 38 school board meeting this week.

Arsenault said he’s hopeful that a couple of his siblings will be able to attend as well. In a way, the Maranacook project proves their point about having their brother buried in a military cemetery.

“We were really pleased with the fact that somebody took the time to visit his grave,” he said.

Susan McMillan — 621-5645

smcmillan@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story