AUGUSTA — The LePage administration unveiled its A-F grading system Wednesday, the latest education reform effort that has already drawn sharp criticism from union leaders and educators.

Statewide, 75 percent of both high schools and elementary schools got a C or lower. For elementary schools, only 12 percent got A’s, and 13 percent got B’s. For high schools, only 10 schools, or 8 percent, got A’s, and 20 schools, or 16 percent, got B’s.

At a press conference in Augusta at the Maine State Library, Gov. Paul LePage said the grades would make schools accountable.

“We grade all our children, and now all we’re doing is taking data that’s in the filing cabinets and putting it out so parents, teachers, administrators, anyone and everyone interested in the schools, in a school system in Maine, to see how they’re doing,” LePage said.

“I want the good schools to be rewarded, and those that aren’t doing as well, we want to be able to help them.”

“It’s for our kids,” he said. “We need to put our kids first … These kids are our future for our state, country and the world.”

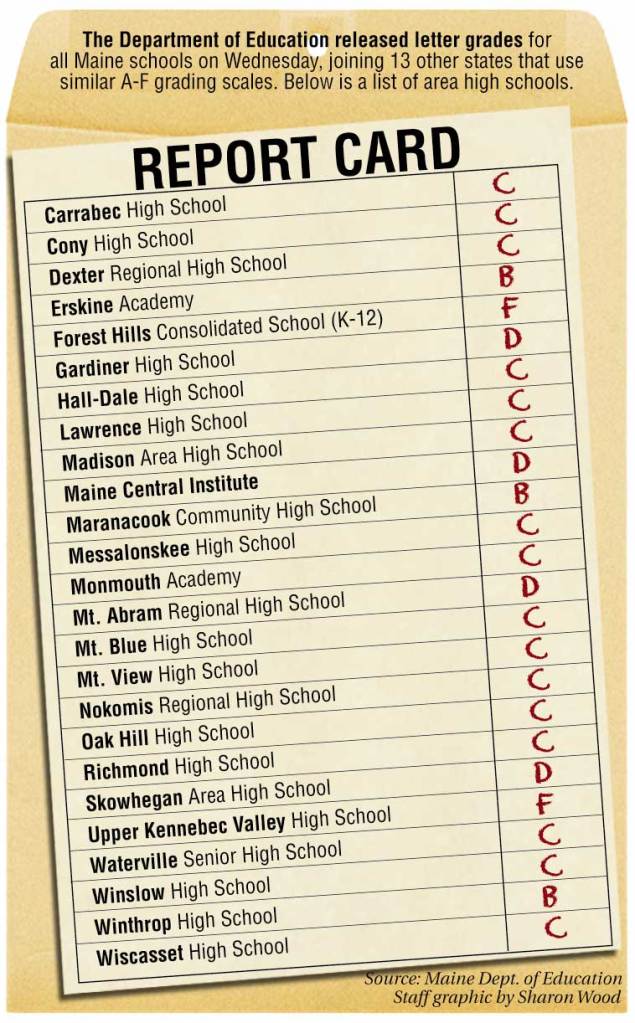

As in most of the state, C was the common grade for schools in central Maine.

Only one school in the Augusta area, Whitefield Elementary in RSU 12, received an F. There were a handful of As, including Hussey Elementary in Augusta and Fayette Central School, which earned scores that placed them both in the top five elementary and middle schools statewide.

Also in central Maine, Augusta’s Cony High School got a C, Gardiner Area High School got a D, and Erskine Academy in China got a B.

Pat Hopkins, superintendent of Gardiner-based RSU 11, reacted to the grades, feeling the grades did not reflect work that has been done recently to improve performance.

In March, Hopkins sent a letter to parents celebrating the gains that RSU 11 students have made on standardized tests in recent years, in some cases surpassing state average scores.

On Wednesday she planned to send home another letter, this time explaining the district’s middling grades, which she said don’t reflect improvements made in the schools.

“I don’t think a simple grade accurately reflects the day-to-day work that’s going on in the classroom,” Hopkins said. “That work is just far more complicated than a single letter grade can provide.

Gardiner Area High School students performed well enough on tests to earn the school a C, but only 94.5 percent of students participated. Because state and federal authorities require 95 percent participation, the school was docked a grade and fell to a D.

An elementary school in the district, Pittston Consolidated School, fell 0.7 points short of a B.

Meanwhile, the two towns in Alternative Organizational Structure 97 had the highest-performing schools in central Maine. Fayette Central School, Winthrop Grade School and Winthrop Middle School all earned As. Winthrop High School received a B.

“It validates the work we’re doing in the schools,” Superintendent Gary Rosenthal said. “So we’re really thrilled.”

Rosenthal said the data show that schools in the district are promoting growth among all students, including the lowest achievers.

AOS 97 schools have below-average rates of low-income students in the area, but Rosenthal said he’s not deterministic about socioeconomic status and school performance.

“I don’t buy a lot of that philosophy,” he said. “I’ve done turnaround work in the past. It’s the expectations you set and the programs you implement that really drive what you’re doing for kids.”

Rosenthal said the grades will probably appear in promotional materials being created for Winthrop Schools.

Around the state, officials of schools that scored low said the revelation that their school was considered failing was devastating.

“I felt like I had been run over by a train,” said Marcia Gendron, principal at East End Elementary School in Portland, which got an F. “I actually thought ‘That can’t be, that’s a mistake.’

East End has been held up by state and federal officials as a huge success story in how to turn around a struggling school. Since Gendron took over two years ago, the school’s math and reading test scores have improved significantly and the school came off the state’s list of persistently low-performing schools.

The fact that it still got an F, Gendron said, illustrates why you can’t sum up the totality of a school and its students in a single letter grade. As a district, Portland’s elementary school grades ranged from A’s to F’s, and the two largest high schools, Deering and Portland high schools, both got a D.

Casco Bay High School, a smaller, expeditionary learning-based school that opened in 2005, got a B.

“What’s unfortunate is that perception is everything, and perception is not always factual,” Gendron said.

State officials are quick to acknowledge that a single grade doesn’t capture many elements, but argued that the simplicity is its strength – people understand a letter grade, said state Education Commissioner Stephen Bowen. And it’s a sure way to get people talking, he said.

“The phones are going to ring. They’ll ring at the principals’ office, they’ll ring at the superintendents’ office and they’ll ring here,” Bowen said from his office in Augusta. “It’s an attention getter.”

That’s why the department released the report cards the same day it unveiled a new “data warehouse” on its website, so parents and other interested people can get detailed data on individual schools. The system has extensive statistics, and the ability to sort and compare among schools, or against state averages.

“We’re hoping people will go in (to the data warehouse) … and ask questions,” he said.

State Democratic leaders were quick to criticize the new grading system.

“We are sending a terrible message to parents, students and teachers in our schools,” said Assistant House Majority Leader Rep. Jeff McCabe of Skowhegan in a release from House Democrats.

“The governor should be marketing our state in a positive way, not shaming our communities and our students and driving down our property values. His grading system is a cynical and demoralizing effort to advance his so-called ‘school choice’ agenda.”

State Sen. Rebecca Millett, who represents Cape Elizabeth and South Portland, is chairwoman of the Education Committee. She said the system was superficial.

“Standardized test scores don’t reflect the accomplishments of our students in art and music, or business and technical education, or even science,” she said in a press release. “The grades penalize those districts that work to keep their students in school longer to make sure they have the appropriate proficiencies before graduating.”

More than a dozen other states use similar grading systems. In general, the grades are based on standardized test scores in math and English, students’ growth and progress, and the performance and growth of the bottom 25 percent of students. For high schools, graduation rates are factored in.

Education leaders, however, say letter grades are too simplistic for measuring a school’s success.

Rob Walker, executive director of the Maine Education Association, particularly criticized the methodology, which he says gives schools in wealthier communities higher grades, while schools with the highest number of students on free and reduced lunch programs – an indicator of poorer families – are “branded with the majority of failing grades.”

In the Portland area, the wealthier communities of Cape Elizabeth, Falmouth and Yarmouth, all already known for their good schools, got A’s for all their schools.

“Research shows that children on free and reduced lunch score lower on standardized tests,” Walker said, “Since when did it become OK to tell poorer communities that their students are failing when they’re faced with obstacles out of their control?”

Connie Brown, the executive director of the Maine School Management Association, also noted that assigning letter grades is at odds with the state’s movement away from assigning letter grades to students. Bowen has strongly supported the move to what’s called standards-based grading.

“It’s really at odds with that,” Brown said. “This is a complete turnaround.”

The letter-grade plan is the latest education initiative of Gov. Paul LePage, who has been sharply critical of public schools. Since LePage took office, the state has opened charter schools and launched a teacher evaluation plan, although he has failed in efforts to get school choice passed, or to provide public funds for religious schools.

His education reforms, including the letter grades, are closely aligned with reforms pushed by a conservative education reform movement that is sweeping the nation. High-profile leaders include former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, former D.C. Schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee and the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council.

Craig Wallace, the state director of StudentsFirst, Rhee’s organization, issued a statement praising the system.

“StudentsFirst has consistently supported A-F grading for schools in an effort to provide parents with the information they need to make informed decisions about their child’s education,” Wallace said.

Critics say such efforts take resources from the public school system, further burden schools and teachers with new requirements and unfairly allocate public funds.

Bowen and others said they hoped to eventually use the school letter grades to identify failing schools and provide state money to help them, perhaps through a $3 million “school accountability” fund proposed in the governor’s budget. That allocation was rejected last month by the Education Committee, and is now before the Legislature’s budget-writing committee.

Department spokesman David Connerty-Marin has described the fund as being similar to the federal School Improvement Grant program, which provides funds to low-performing schools.

It would use state funds to assist schools that don’t qualify for federal assistance under Title I, the program that puts money into economically disadvantaged school districts, he said.

IMPACT ON COMMUNITIES

Several Democrat legislators in Maine have said they’re worried about what a failing grade may mean for local communities, particularly on real estate prices, or in drawing new businesses that look at quality of life factors such as schools, to attract workers.

In Arizona, the report cards play a big role in the real estate market, according to Jennifer Sanchez, a real estate agent in the Phoenix area.

Sanchez said she sends parents to websites with information about school performance, and that generally dissuades them from even considering areas with low-rated schools.

One factor that may lessen the impact of school grades on real estate in Arizona is the availability of school choice options, such as charter schools and open enrollment, that mean a student’s school is not determined by address.

Many schools with an A or an A-plus hang banners out front to boast of their grades, Sanchez said.

“In one aspect, it creates healthy competition among schools and principals,” she said. “They want to achieve more and they want their state standardized testing to be high to get those ratings.”

While academic experts are divided on whether school report cards lead to student improvement, a key question is what exactly is being measured. In Maine, officials said they intentionally launched the report cards with very few factors, as opposed to states such as New Mexico, which uses a complex formula to grade schools.

David Figlio, professor of economics and of education and social policy at Northwestern University, said he’s agnostic on the question of whether to have report cards for schools, but he likes the design of Maine’s.

“If we are going to see a school grading system, I like something like what Maine’s done,” he said. “Because the combination of looking at growth and proficiency rates means that there’s some reward to having high proficiency, but on the other hand it’s fairer to schools that serve less advantaged student bodies.”

Growth measures are also less susceptible to manipulation by school staff, such as strategically suspending students they expect to score low on proficiency.

In his research, Figlio has found that school report cards and grades have real effects on perceptions and activities both inside and outside schools.

“In the case of Florida, for example, there was lots of information that was already kind of percolating out there about school quality,” Figlio said. “But when the state came in and summed it up in an easy to digest letter grade, people paid attention to it.”

In a 2004 study of school grades’ effect in Florida, Figlio found that the school grades drove up home prices in neighborhoods with top-rated schools.

Community members also tend to voluntarily give more money to schools with high grades, while withdrawing support from fundraising at schools with low grades, Figlio said.

The grades also affect the behavior of school staff. Some react negatively, by cheating or otherwise trying to game the system.

Other schools make attempts at real change, Figlio said, by restructuring the school day or exploring alternative ways to group students by performance.

And the grades do appear to have a small positive effect on actual learning, Figlio said, at least when it comes to the subjects that are tested, usually math and reading.

Less certain is what’s happening with student knowledge of the humanities or the arts, or skills such as critical thinking.

“It’s not a silver bullet,” Figlio said. “It doesn’t revolutionize the way schools are doing business, it doesn’t turn mediocre schools to outstanding schools, at least overnight. I’m still agnostic on the policy, in part because I see costs to it, but I do see these benefits as well.”

QUESTIONS ABOUT FAIRNESS

Several superintendents in southern Maine criticized the letter grades, even in districts that got all A’s and B’s, as failing to capture the many elements that go into a school community, and measuring student success.

In Portland, the elementary school grades ranged from A’s for Longfellow and Peaks Island, to F’s for East End and Hall schools.

“It’s hard to capture some of the issues that are particular to Portland,” said Portland School Board President Jaimey Caron, referring to the city’s large populations on non-English speakers and lower income students.

“My concern is that (grading schools) leaves too much to the imagination of the parent or the taxpayer. We don’t want people to spend a lot of energy on things that are not real,” Caron said. “I agree that it’s important to characterize the performance of a school, but it has to be a metric that has meaning.”

In Sanford, Superintendent David Theoharides said the high school’s D and C grades for the elementary schools do not reflect the “amazing things” the district is doing. He pointed out that the district recently got new school construction funded, got a large Nellie Mae grant and had one of their teachers honored as the Maine Teacher of the Year just a few years ago.

“I see great things happening,” Theoharides said. “I also see a community that struggles economically. Is this a grade that measures the effectiveness of the school or the socioeconomic status of the community?”

Even in districts with high grades, there was criticism of the formula.

“It’s brushing your school with a very broad stroke,” said Kennebunk Superintendent Andrew Dolloff, whose schools all got A’s or B’s. “I sympathize with those whose grades aren’t as strong as their communities would like to see.”

There was also some concern about the accuracy of the data, and changes were being made to the grades right up until just before the press conference, after schools got the grades and reviewed the data. Dolloff said the state told him Kennebunk High School got a B, but when he checked the data, it should have been an A. The grade was changed after state officials acknowledged the computer was not programmed to round off numbers, so it read Kennebunk’s 94.9 percent participation rate as less than 95 percent – and penalized the school a full letter grade.

Several other superintendents called with concerns, according to William Hurwitch, the director of the state’s educational database.

Only minutes before the 1 p.m. press conference, the education department released changes to the database that excluded all of Westbrook’s elementary schools.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story