Humans are dumping so much carbon dioxide into the oceans so fast that seawater — even in the Gulf of Maine — is getting warmer and more acidic, according to marine and climate researchers.

Scientists aren’t sure yet how the trend, which is believed to be tied to human-induced climate change, will affect ocean life in the gulf. But there is rising concern — especially among fishermen — that changes in the ocean ecosystem could severely damage some of the fisheries that are the backbone of the region’s seafood industry.

The effects of warming and acidification are showing up all over the world, including in and along the gulf.

“We’ve seen levels of acid that rival some of the highest levels recorded anywhere,” said professor of marine science Mark Green, whose work at St. Joseph’s College in Standish has focused exclusively on ocean acidification. “Many coastal areas are increasing three times faster than open ocean.”

Lobsters are up, cod down. The herring caught in the gulf are much smaller than they were 20 years ago, marine scientists have observed. Northern right whales might leave altogether if populations of plankton are reduced enough to affect the whales’ food supply.

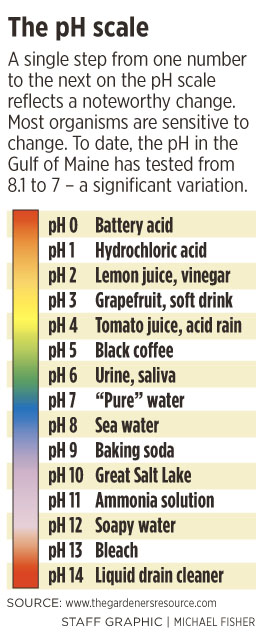

Ocean acidification is a long, slow process in which seas absorb excessive amounts of carbon dioxide, enough to alter pH levels (the percentage of hydrogen, which is a measure of acidity and alkalinity).

Global surface waters have an average pH of 8.1, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. But scientists believe that level could drop in the next 50 years to as low as 7.8, a huge change.

The impacts of increased carbon dioxide go far beyond making the water warmer and more acidic. Many species are weakened by the loss of oxygen and the spread of infectious diseases can speed up when water temperatures rise. Higher carbon dioxide levels in the ocean lead to an increase in carbonic acid, which reduces the availability of structural materials that mollusks and crustaceans need to form their shells.

The ranges of many species of sea life have been changed. Green crabs, for example, have moved in on shellfish beds in Maine from the more southerly waters they have traditionally inhabited.

“That’s the really compelling story — that there will be winners and losers,” said Rick Wahle, research associate professor in the School of Marine Sciences at the University of Maine.

Absorption of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the ocean waters has increased to about 100 times what it was 600 years ago, Green said. On average, ocean carbon dioxide levels are up 30 percent, most of it absorbed in the past 50 years. Exacerbating the problem is runoff from rivers polluted by fertilizer and soil erosion, and millions of tons of untreated sewage pumped into coastal waters, including Casco Bay.

Debate swirls about which stressors are to blame for which consequences, but one fact is undeniable: Ocean temperatures are rising and the water is becoming more acidic. The increased carbon dioxide in air and water comes largely from the burning of fossil fuels and emissions from factories, cars and power plants, most scientists say.

A SERIOUS AND COMPLEX ISSUE

Some of the early evidence has been revealed by testing of pH levels in costal seawater and the monitoring of water and air temperatures over the past 15 years or so.

“I consider it to be an issue that merits better understanding,” said Jeff Runge, professor of oceanography in the School of Marine Sciences at the University of Maine and a researcher at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in Portland.

“It’s starting to be recognized as a serious issue,” he said. “But it’s very complex. We’re just not doing a very good job yet in understanding the biological and ecosystem effects in the Gulf of Maine.”

Exactly what the changes mean and how they’ll play out — for marine life and the thousands of Mainers who get their livelihoods from the sea — is not yet clear.

But it is no small matter. In 2012 alone, Maine’s fisheries accounted for $521.5 million in revenue, with lobsters bringing in $349 million; soft-shell clams, $15.3 million; scallops, $2.9 million; blue mussels, $1.9 million; cod, $1.6 million; and oysters, $1.45 million, according to the state Department of Marine Resources.

“The clammers in our community (about 50 families) are very concerned about this … and about losing their livelihoods,” said Kristina Egan, vice-chair of the Freeport Town Council, which last year allocated $100,000 for a study of increasing numbers of green crabs overrunning the shellfish flats and eating immature clams.

“We’re also concerned about losing this historic industry in Freeport,” she said.

Chad Coffin of Freeport, president of the Maine Clammers Association, says he believes ocean acidification is real, but it is not certain how serious it is for clammers or what can be done about it.

“I don’t think it’s a particularly big issue for the shellfish industry,” Coffin said.

But the impact of green crab migration on shellfish beds is an immediate concern, he said.

“We’re in big trouble,” he said. “Green crabs have already eaten their way through the scallops, urchins, mussels and now clams.”

If these aggressive predators are not stopped, he said, they could wipe out the resource and move on to lobsters — a view shared by Carl Wilson, a marine resource scientist with the state Department of Marine Resources.

Freeport officials say they believe the crabs have proliferated because of at least a decade of relatively warmer winters and ocean temperatures that no longer dip much below 40 degrees — not cold enough to cause the seasonal die-offs that keep the crab populations in check.

At least that’s the theory. But there are still many unanswered questions about ocean acidification’s effects on the state’s fisheries.

“We are still learning about the details and implications,” Wilson said.

“Ocean acidification is going to happen over a long period,” he said. “The two (climate change and ocean acidification) are interrelated.”

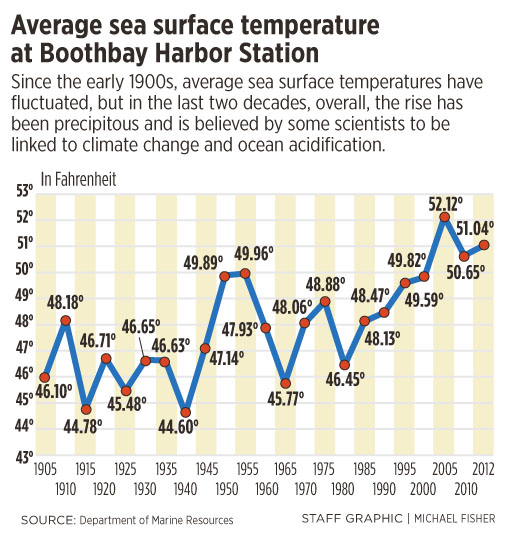

Wilson noted that a century of records from Boothbay Harbor indicate that eight of the 10 warmest summers have occurred in the past decade. Most researchers and observers agree that conditions in the gulf are markedly different than they were even 20 years ago.

LOBSTER HARVEST ‘PRECARIOUS’

Many fishermen fear that the changes do not bode well for the species they harvest. Though Maine lobstermen have enjoyed an almost quantum leap in their harvests in recent years, with a record haul in 2012; shellfishermen are struggling, and groundfishermen have watched their fishery virtually dry up.

“This very high abundance of lobster is very precarious,” said Wilson. “That’s the lesson we learned from southern New England and Cape Cod — warm water and other factors led to an eventual crash.”

The annual lobster harvest has skyrocketed from 20 million pounds to nearly 125 million pounds in the past 25 years, and Wilson said there are no indications that the lobster population is going to collapse. The species is expanding in its northern range, and the distribution of lobsters is increasing east of Penobscot Bay. But populations south of Penobscot Bay may not fare as well, he said.

Wahle, the UMaine marine scientist, noted that ocean conditions in Maine are becoming more like Rhode Island or southern New England.

“That, in itself, is a bad thing,” he said.

Rhode Island, New York and Connecticut have seen their lobster fisheries decimated by shell disease, first diagnosed in the 1980s and now linked to warmer water temperatures. The infection damages the exoskeleton with black spots, pits, ulcerations, and sometimes total rot. The disease does not taint the meat but renders the lobsters impossible to sell.

New York’s $100 million industry has been crippled, affecting thousands of families, and the Connecticut Lobstermen’s Association estimates the loss there at about $16 million per year.

The infections have not yet had a significant impact on Maine’s lobster fishery; less than 1 percent have been infected, compared with 30 percent in southern New England, said Wahle.

“Those levels put the fear of God in Maine lobstermen,” he said. We are perilously dependent on this one fishery.”

Wahle said he has seen a slight uptick in the disease. “That raises some red flags for me,” he said.

Wilson, at the marine resources department, sees an important change in people — and how they regard the environment. In the 1970s, he said, environmental effects were assumed to be simple and relatively fixed.

But those days are over, he said, and science has yet to unravel the complex relationships among the factors that contribute to acidification, and the effects of that trend.

As perceptions of what is normal vacillate, the implications for fisheries management are profound.

“There are nuanced impacts,” Wilson said. “If you’re in a changing environment … everything that’s up is now down. You think you understand the system and you make your recommendations accordingly.”

North Cairn can be contacted at 791-6325 or at:

ncairn@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story