The public’s access to government information is under attack in Maine.

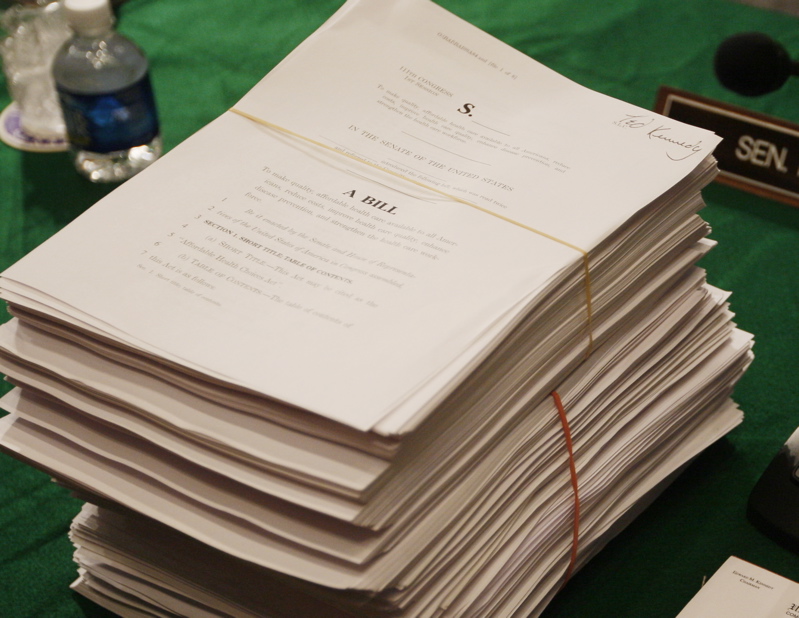

The Legislature will take up several bills this session that would further puncture the state’s open-government law, snatching from public view information that is now considered part of the public’s right to know.

If approved, the measures will reinforce Maine’s national reputation as a place where transparency and government accountability rank behind privacy and other powerful interests.

The proposals include bills that would block access to information about individuals who hold concealed-weapons permits, allow police to withhold transcripts of 911 calls, and shield the email addresses of citizens who sign up to receive notifications from government groups.

If adopted, the proposals would lengthen the list of 483 exemptions that previous legislatures have already carved out of to the right-to-know law. Many more exemptions are woven into the governing statutes of various state agencies.

These exemptions, combined with a weak and costly appeals process for the denial of public records, and what some describe as a cultural reluctance to expose personal information collected by public officials, have positioned Maine as a state that does not value transparency.

“I don’t think of Maine when people ask me which states are shining examples of sunshine,” said Ken Bunting, executive director of the National Freedom of Information Coalition.

Sigmund Schutz, a Preti Flaherty media attorney whose clients include the Portland Press Herald and Maine Sunday Telegram, describes Maine’s open-government law as “all over the place.”

“It’s good in some places, but really bad in others,” Schutz said.

Maine’s Freedom of Access Act, adopted by the Legislature in 1959, stipulates that all records are public so long as they are used in the transaction of governmental business. But through liberal use of rulemaking, state lawmakers have reduced “all” records to “some.”

Open to public inspection are records such as tax assessments; visitor logs for state offices, including jails; the schedules of elected officials, including the governor, attorney general and the secretary of state; arrest logs; and transcripts of emergency dispatch calls.

But the Legislature has made myriad changes to the law to exempt documents from public view. Many exemptions have been made to protect personal identifying information during sensitive interactions with government, including information about who receives government assistance or data that could identify crime victims or impede police investigations.

Other exemptions are more arcane. One, adopted in 2001, shields the list of growers using genetically engineered plants. Another proved self-serving for state lawmakers, who voted in 1991 to shield their “working papers,” or communications related to the drafting of legislation. Gov. Paul LePage, citing legislators’ exemption, tried to obtain the same privilege in 2011, but the proposal was rejected.

Lawmakers periodically offer bills to strengthen the law, but those proposals face long odds, often traceable to the push-pull struggle between privacy and transparency.

Bunting, of the freedom of information coalition, said that unlike heavily populated states, Mainers’ close proximity to their elected officials and their government may make them more inclined to let government and its records remain private, or in some instances become that way.

“In a state like Maine there is a shorter distance … between the people and those city councils, school boards and lawmakers who see any liberalization of transparency laws as a threat,” Bunting said.

BILLS CURRENTLY PROPOSED

Bills in the current legislative session that would seal off public access to government records include a measure sponsored by Democratic Rep. Mary Nelson of Falmouth.

An outspoken critic of Falmouth government used the open-records law to obtain about 3,000 email addresses of subscribers to the town’s electronic newsletters. The critic used the addresses to distribute information during a campaign to end Metro bus service in Falmouth.

Nelson, who recently testified on behalf of the bill, argued that subscribing to town newsletters should not trigger “unwelcome, townwide solicitations or even identity theft.”

Another legislator, Rep. David Burns, R-Whiting, is sponsoring a bill to shield 911 dispatch transcripts. The proposal was submitted after the Portland Press Herald filed a lawsuit in Cumberland County Superior Court asking a judge to overturn the state’s denial of the newspaper’s public-records request for 911 transcripts associated with an open homicide investigation in Biddeford.

Privacy, public safety and the threat of identity theft are being cited to support a bill by Rep. Corey Wilson, R-Augusta, that would make concealed-weapons permit data confidential. The data has been public since 1981, when Maine’s concealed-weapons law was enacted.

Wilson’s bill was filed after a New York newspaper, in the wake of the Newtown, Conn., school shootings, published lists and an online map of all handgun permit owners in two counties. Support for Wilson’s bill mushroomed when the Bangor Daily News filed a request for Maine concealed-weapons information last month.

That request was later withdrawn, but it stirred such concern that the Legislature overwhelmingly passed an immediate, 60-day ban on releasing concealed-weapons information, until Wilson’s bill can be heard and debated.

Laurenellen McCann, a national policy expert for the Sunlight Foundation, said many efforts at the state level to take information off the public record have a narrow focus. But she said these efforts to address isolated problems can have a cumulative impact on government transparency.

That’s the concern among open-records advocates in Maine, who were dealt a blow when the Legislature passed the emergency measure to temporarily shield the concealed-weapons data.

“We took a hit,” said Judy Meyer, managing editor of the Sun Journal in Lewiston and vice president of the Maine Freedom of Information Coalition. “And when I say, ‘we,’ I don’t just mean the press. I mean we the people.”

AUDIT SHOWED POOR COMPLIANCE

Concerns about Maine’s willingness to open government to public scrutiny are nothing new.

Just over 10 years ago, the Maine Freedom of Information Coalition dispatched a team of volunteers across the state to request public records from towns and police departments.

An audit report on the effort documented woeful compliance with the laws, including instances during which the volunteer auditors, some college students, were either denied or intimidated by police officers for requesting public documents.

The audit, highly publicized on New Year’s Day in 2003, prompted action by the Legislature, which was “embarrassed,” according to Mal Leary, president of the coalition.

State and local public officials now receive mandatory training to help comply with the law, and lawmakers established the Right to Know Advisory Committee, which reviews proposed changes to the law and offers recommendations to the Legislature’s Judiciary Committee.

“We try to get rid of the bad (exemptions) and prevent new ones,” Leary said. “Not many other states have that process.”

Still, states like Texas, Florida and Vermont have much stronger sunshine laws. In Florida, government transparency is written into the state constitution, which means that attempts to change or weaken the law require a supermajority of the Florida Legislature or a citizens initiative.

Not so in Maine. Not only can the Legislature easily alter the open-records law, but it also appoints members to the Right to Know Advisory Committee.

Although the panel is populated by open-records advocates, Schutz, the media attorney, said it has also included “complete failures” and “government types.” Schutz’s didn’t identify specific members, but noted that the panel is appointed by the governor, the Senate president and House speaker — politicians whose interests may not always align with open-government efforts.

“Sometimes you get this notion from a few of them that government would work a lot more smoothly and efficiently if it didn’t have to worry or bother with public reactions to what they’re doing, or public accountability,” he said. “For some of them it’s as if they believe, ‘we could get a lot more done if we were just allowed to do things in secret.’ “

GOV. LEPAGE AN ‘ENIGMA’

Transparency and open government are now buzzwords for politicians who recognize the populist value of lifting the veil on government business — at a time when opinion polls repeatedly document the contempt many citizens have for elected officials.

LePage vowed to have the most transparent administration in state history when he ran for governor in 2010. He devoted an entire page of his campaign website to the policy endeavor.

“Every Maine citizen has a right to know what government is up to,” the site read. “He will fight for stronger laws to protect and expand Maine citizens’ right to access information from state and local government. When Paul is Governor, open government will be a reality, not a talking point.”

LePage has taken several steps to increase government transparency. He signed a law to close a disclosure loophole that allowed lawmakers and state officials to profit from state-paid contracts. He recently unveiled Open Checkbook, a site that allows the public to track government spending.

And he funded the position of ombudsman in the Attorney General’s Office to mediate disputes over public records access between citizens and government.

But it’s unclear what the ombudsman has accomplished since the position was filled in September.

Leary, at the freedom of information coalition, said LePage has been an “enigma” on the public’s right to know. In 2011, LePage created a work group of business leaders and, through executive order, exempted the meetings from the public-access law.

Last year, LePage claimed that political opponents and some news organizations were using the state’s FOAA law as a form of “internal terrorism,” inundating his administration with “nuisance” records requests, including one for the Blaine House grocery bill.

The governor later said that such requests were behind his proposal to exempt his administration’s “working papers” from public-disclosure requirements, including correspondence related to potential legislation and policy matters.

The proposal was soundly defeated. However, LePage later told Leary, who was the owner of the Capitol News Service at the time, during an interview that he’d instructed his staff to limit its use of email and written correspondence to avoid the Freedom of Access Act.

Leary recalled the interview, saying, “He told me, ‘They can’t FOAA my brain.’ “

PUBLIC RECORDS ‘SHOULD BE ONLINE’

Public officials frequently lament that they’re inundated with public-records requests, some of which can be used to embarrass them. Some contend the requests are too broad and time-consuming.

The Sunlight Foundation’s McCann said government officials should worry less about the intent of public-records requests and more about finding ways to make the information readily available on the Internet.

She noted that states such as Utah are considering proposals that would make it easier and cheaper to access public records information using technology.

“Understanding that public information should be online reduces the burden on everyone,” McCann said. “It should also take care of a lot of costs.”

Other states have been more aggressive in moving toward transparency.

In North Carolina, a lawmaker recently introduced a bill that would criminalize an illegal denial of public records, with a $200 fine and up to 10 days in jail. It’s unclear if the bill has much traction, but it’s a stark contrast to efforts in Maine where, as Schutz noted, there are few penalties or other disincentives for violating the open records law. It’s also expensive to challenge rejected requests.

“You have to go to Superior Court,” Schutz said. “If you go to court there’s no way to recover legal fees. There’s no real strong incentive or remedy.”

The prospects for improved transparency in Maine appear to be dim.

Open-records advocates had hoped to focus their energy in the current legislative session on beefing up public access. Instead, at least in the case of the concealed-weapons bill, they’re struggling to keep records in the public domain that have been there for 32 years.

Complicating the debate is the sense of emergency — real or not — and the highly polarized positions surrounding the issue of guns.

Bunting, at the National Freedom of Information Coalition, said bad things happen when decisions that affect transparency are made in such a charged atmosphere.

“As a rule, when an open-records law is amended in response to an uproar, it’s usually not good for the law,” he said.

Steve Mistler can be contacted at 620-6016 or at:

smistler@pressherald.com

On Twitter: @stevemistler

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story