Sometime in the dark hours of Nov. 14 or 15, James Cameron cut off the electronic monitoring bracelet that had tracked his whereabouts for 14 months.

Then he slipped quietly into the night. He hasn’t surfaced since.

Former co-workers have called Cameron honest, a tough prosecutor who led a quiet life. He seemingly had few interests besides his work, except a love of watches and watchmaking, a hobby that ultimately helped trigger the criminal case against him.

Cameron disappeared less than a day after a federal appeals court in Boston failed to overturn all his child pornography convictions from 2010. He had been out of prison on bail for more than a year pending the appeal, but this was likely his final chance at salvation. Now, Cameron was set to return to prison.

Family members told police that Cameron, 50, was “not doing well” in prison prior to his release. He had lost weight and his hair had gotten grayer. In court, he had to hold up the seat of his pants when he stood up. It’s no surprise that a man who had spent a career fighting criminals didn’t fit well among them.

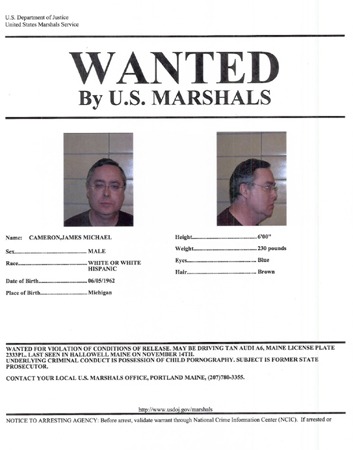

So he fled, risking additional prison time, taking little more than his car — a late-model tan Audi A6 — and his laptop computer.

According to police accounts, Cameron had an 11-hour head start before authorities launched a nationwide manhunt.

Noel March, the top U.S. marshal for Maine, said he’s confident Cameron will be found, despite the fact that he has considerable knowledge of the justice system and investigative procedures learned during 20 years as one of Maine’s top prosecutors, a man who might have one day been a candidate for district attorney, attorney general or even a judge.

Michigan to Maine

Cameron grew up in Michigan and graduated from the University of Detroit’s Mercy School of Law in 1987. He came to Maine two years later.

He was still shy of his 30th birthday when he was hired by the Maine Attorney General’s Office in 1990. Many of the assistant attorneys general who focus on drug cases are assigned to work in county district attorneys’ offices. Cameron was posted in Kennebec County for many years before moving to the AG’s main office.

“He seemed to have a good reputation,” said Darrick Banda, who worked as an assistant district attorney in Kennebec County from 2003-08 and is now a defense attorney. “No one had anything bad to say.”

Walter McKee, an Augusta attorney for many years, said he knew Cameron well and faced him in court more than once.

“He was a very competent, aggressive prosecutor; a worthy adversary, quick on his feet,” McKee said.

David Crook, a former district attorney in Kennebec County who is now a defense lawyer, in a 2011 story described Cameron as “a man of integrity,” and “totally honest.”

Cameron built a reputation as a sharp and methodical prosecutor, but few who knew him professionally knew anything about his private life.

Banda said that at the Maine prosecutors’ conference in Bar Harbor every year, many attendees would go out for drinks at the end of each day.

“He just wasn’t a part of that,” Banda said.

McKee lived within walking distance of Cameron but didn’t interact with him outside the courtroom.

“He was a private person,” McKee said.

Cameron was an adjunct faculty member at Thomas College in Waterville, teaching constitutional law from 2001-07. College officials refused to say whether Cameron was fired or left on his own.

William Stokes, the head of the criminal division for the AG’s office, said he knew Cameron well but declined to talk about him. In fact, no one who still has ties to the AG’s office wanted to talk about Cameron.

Steve Rowe, Maine’s former attorney general, was his boss for eight years. Court documents referred to Cameron as a “close advisor” to Rowe, who ran unsuccessfully for governor in 2010.

Reached by telephone last week, Rowe was silent for a long moment when Cameron’s name came up.

“I’m not going to talk about that,” he said. “I’m sorry.”

The watch business

Cameron and his wife, Barbara, married when he was 22. They had two children, a boy and a girl, and owned a home in Hallowell and a camp in the desirable Belgrade Lakes area.

One of Cameron’s few hobbies was watches: rare, expensive watches and vintage military watches. After he was fired from the AG’s office in 2008, Cameron and his brother began selling watches and producing replica watches. They founded Corvus Watch Company, which has a good reputation in the business, according to online forums for horologists, or watch enthusiasts.

Cameron also had been writing a book about Barton Watson, a childhood friend who was the former CEO of a Michigan company called CyberNET Engineering. Watson amassed considerable personal wealth in part by receiving fraudulent loans and lying about his business operations, which funded a lavish lifestyle that he often boasted about on travel websites. Watson committed suicide in 2004, less than a week after federal authorities raided his business on suspicion of fraud and discovered that he owed creditors $100 million.

Cameron appeared on the television show “American Greed” to talk about Watson, whose fall from grace fascinated him.

In the middle part of the last decade, coworkers at the AG’s office said Cameron became less reliable around the office, although there appeared to be no obvious cause. He was gone for long stretches and often worked from home. A former secretary testified during trial that his unexplained absences prompted a running joke: “Where in the world is Jim Cameron?”

During closing arguments at the trial, Assistant U.S. Attorney Donald Clark brought it up again.

“Where in the world is Jim Cameron? We know the answer. He was at home, on his computer, trading child pornography,” Clark said.

Discovered

On Aug. 3, 2007, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a clearinghouse for referring illicit online activities, notified Maine State Police that someone had uploaded images of child pornography onto a Yahoo account. A second referral was made on Sept. 6.

In both instances, photos of victims as young as 4 years old were viewed between 1 and 7 a.m. The Internet protocol address used was traced to a home in Hallowell, and a Yahoo account belonging to Barbara Cameron.

On Dec. 21, 2007, police searched Cameron’s home and seized four computers.

According to investigators, Cameron was calm during the search, suggesting that someone from outside the home might have been responsible for the explicit images. He also said it was possible that they were downloaded by his then-12-year-old son, who is autistic.

Sgt. Glenn Lang of the Maine State Police Computer Crimes Unit, who led the investigation, called it the “most time-consuming case we’ve ever done.” He said two things made the case unique: The high-profile nature and Cameron’s sophisticated attempts to scrub his hard drives.

“The case proves that no matter how many tools are out there, there is usually a way to find out someone’s online activities,” he said.

It was actually Cameron’s interest in watches that helped investigators make the link. There were numerous searches about watches mixed in with searches of child pornography, supporting the assumption that it was Cameron at the keyboard.

Convicted

On Feb. 11, 2009, almost 14 months after his home was searched, Cameron was indicted by a federal grand jury on 16 counts of transporting, receiving and possessing child pornography.

It took that long to bring an indictment, Lang said, because Cameron admitted nothing, forcing someone to pore through every file and then pinpoint the exact time each file was downloaded.

Before the case went to trial, Rodway negotiated a plea agreement with U.S. Attorney Gail Malone, according to court documents, in which Cameron would plead guilty to two of the 15 counts against him. The remainder would be dropped. Cameron would probably have served less time.

But he backed out at the last minute. Rodway resigned as counsel and was replaced by a court-appointed attorney, Michael Cunniff.

During the six-day trial, details of his life and computer habits were methodically detailed. There was one point during which it appeared Cameron might take the stand in his own defense, but that never happened.

On Aug. 23, 2010, U.S. District Court Judge John Woodcock found Cameron guilty.

“Mr. Cameron, you had so much to lose, and now you’ve lost it,” Woodcock said during sentencing.

Cameron didn’t admit his guilt until his March 2011 sentencing.

“I am guilty and I stand here ready to face punishment with the greatest respect for the judicial process. That said, I am deeply ashamed of myself and offer no excuses for my conduct,” he said. “I also want to say that I am deeply sorry for the loss and pain suffered by all victims of sexual abuse.”

He received 16 years.

Bill Diamond, former secretary of state and a longtime state lawmaker from Windham, has studied sex offenders at length and recently wrote a book about the topic. In it, he describes Cameron as a cautionary tale.

“(He) illustrates the fact that sex offenders are often not the creepy looking guy everyone imagines wearing a trench coat peering at little children from behind a tree, but more likely someone who has the trust of family, friends and coworkers, which is, of course, the best disguise of all,” Diamond wrote.

Cameron knew, perhaps better than anyone, about the penalties for child pornography and still couldn’t stop.

“The need to view those images was likely stronger,” Diamond said recently. “It’s like a drug addiction.”

Appeal

Cameron was transferred to a federal prison in Littleton, Colo., but didn’t stop trying to overturn his conviction.

A judge finally granted his release from prison pending appeal, aided in part by a U.S. Supreme Court decision that cast doubt on the government’s ability to uphold the conviction.

He was released on several conditions:

* He would return to Maine, where his ex-wife would be responsible for him.

* He would adhere to a curfew.

* His Internet activity would be closely watched.

* And he would wear an electronic monitor.

After a year, the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston vacated six of his convictions on the ground that certain evidence presented at trial was inadmissible because Cameron’s attorney did not have the chance to question some witnesses. The appellate court upheld the remaining seven convictions.

The matter was supposed to be sent back to U.S. District Court in Maine so Cameron could be resentenced. Because almost half of the charges were dropped, it is likely his sentence might have been reduced.

Peter Horstmann, Cameron’s attorney during the appeals process, said he still expects all the counts against Cameron to be vacated.

Until he fled, Cameron had adhered dutifully to his bail conditions. He had even been allowed to leave the country before he was indicted, a point prosecutors brought up initially as a concern. But Horstmann said Cameron always came back.

Flight

On the evening of Nov. 14, Cameron visited his Hallowell home and told his ex-wife and son he would be going back to prison.

Cameron’s monitoring bracelet indicated that he returned to his camp in Rome at 8 p.m. A witness confirmed to police that Cameron was seen in Rome that night.

At 12:46 a.m. on Nov. 15, Cameron left his home without authorization. About an hour later, his probation officer got no response when he called Cameron’s home and cell phones. The officer then unsuccessfully tried to call Cameron again between 7 and 8 a.m.

Police went to the home about 10:30 a.m. U.S. Marshals were notified by noon.

Judge Woodcock issued a warrant for Cameron’s arrest that day. The public was notified days later.

Police have since searched his ex-wife’s home, but found no traces that Cameron was there.

Marshals don’t consider Cameron a threat, at least not to others. He is savvy, though. He knows, in theory, how to stay head of investigators. Nearly 11 hours elapsed from the time he cut off his bracelet to the moment police showed up at his door. He reliquished his passport as part of his bail conditions but in that amount of time, he could have gotten as far as Ohio or Virginia.

Cameron has family ties to Michigan, where authorities are keeping an eye out, according to U.S. Marshals.

Marshals are following up on any leads and tips that come in, but have refused to say whether they have received any.

Bruce Merrill, an attorney who has represented Barbara Cameron in the past, said she has declined any interviews in order to protect her children.

“She’s been trying to put this behind her ever since it happened,” he said.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story