EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third in a series of profiles of the U.S. Senate candidates.

SCARBOROUGH — Five years ago, Charlie Summers was lying on the floor of an unfortified sleeping trailer in Baghdad’s Green Zone as mortars fell nearby. He turned to his roommate, a fellow Navy reservist who was married to the best friend of Summers’ wife.

“I said to Mike, ‘Who talked you into joining?’ ” Summers recalls with a laugh. “He said: ‘Your wife’! And I said, ‘Me, too. Look at where we are, and look where she is!’ “

While her husband was taking fire in Iraq, Ruth Summers was on the political front lines back here in Scarborough, running his tenacious campaign to represent Maine’s 1st District in Congress. Though prohibited from campaigning until he returned to the States in June 2008, Summers won his party’s primary, but would go on to lose the seat for the third time to a Democratic rival: this time, incumbent Rep. Chellie Pingree.

“Just because you get knocked down, it doesn’t mean you can’t get up and do it again,” Summers says of the chain of losses. “If you lose an election, two elections, whatever it is, if you look at it as a learning process and ask how you could have done it differently, it makes you a better candidate.”

Now Summers is the Republican nominee for the U.S. Senate seat currently held by his estranged political mentor, Olympia Snowe. While he last won a popular election 20 years ago, the tall and affable secretary of state hopes his accumulated life experiences will make the difference this time, allowing him to upset the apparent front-runner, two-term independent former Gov. Angus King.

Those experiences have brought Summers from his parents’ hotel in a small Midwestern town to stints as a state senator, regional small business administrator and secretary of state, as well as state director for Snowe and military deployments to Iraq, Afghanistan and the Pentagon. With the support of his wife — who suceeeded him as state party vice chair and is running for his old state Senate seat — he hopes to bring his congenial style to a legislative body paralyzed by dysfunction and partisan gridlock.

RAISED IN HOSPITALITY

Charles E. Summers Jr. was born the day after Christmas 1959 in Danville, Ill. He was the fourth of five children in a family of hoteliers. His great-grandfather had founded a hotel in Mt. Vernon, Ill., and his uncle owned two in Alton. At the time of his birth, Summers’ parents were leasing a local hotel, but in 1960 moved to the northwestern part of the state and into the Hotel Kewanee, a failing establishment they had just purchased.

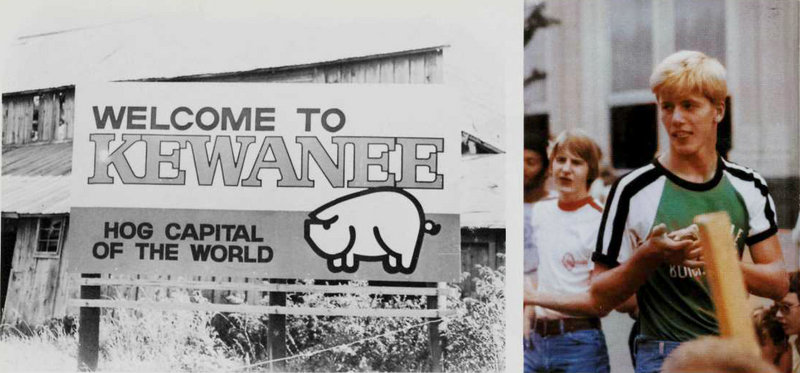

Built in 1916, the hotel was in the center of Kewanee, a town of 10,000 that billed itself as “the hog capital of the world.” Summers describes the town as “a cross between Presque Isle and Biddeford” in that when he was growing up it was a small industrial community surrounded by flat, open farmland. But by the time he was in grade school, it had started its long decline.

“This is typical Rust Belt,” says local veterinarian Tom Schwerbrock, who attended Kewanee High School with Summers and has seen many of the factories close and the farms consolidate. “We’re nowhere near being the hog capital of the world today.”

The hotel was the most prominent in town, a four-story structure with a bar, ballroom, full restaurant and the studios of two radio stations on the top floor. It had bankrupted its two previous owners.

“It was the place to stay in Kewanee, and when they ran it the restaurant was one of the nicer places to eat,” Schwerbrock recalls. “It was a tight ship.”

Summers was literally raised in the hotel — the family lived in a second-floor apartment — and he and his siblings joined in to keep it running.

“It was truly a family business: We all worked at the front desk, the kitchen, the bar. We all did whatever it was that needed to be done,” he recalls. “Unlike most kids growing up, if your mother or father are working they are gone and you were alone in the house. At a hotel, you’re never alone because there were also the clerks and the restaurant or the bar or the radio station.” It was, he says, a world unto itself.

Children would come to peer through a glass wall at the WKEI staff and their automatic tape changers. “Charlie and his little brother Ray used to harass us, making faces through the glass and running away when we would go and chase them off,” says former disc jockey Dave Clarke. “They’d yell back that their dad owned the hotel!”

The hotel ballroom attracted politicians, because local Republicans rented it out to stage events whenever one of their luminaries passed through. Charlie met them all — Richard Nixon, George H.W. Bush, Barry Goldwater and future Texas Sen. John Tower — but it was Illinois Sen. Everett Dirksen whose visit to his family home/hotel made the greatest impression.

“Dirksen was the kind of politician I knew growing up, the kind of person who would work with Lyndon Johnson and the Democrats to get things done, like getting civil rights legislation passed,” Summers says of the former U.S. Senate minority leader.

In Kewanee, Summers says, “The Democrats worked in the factories and the Republicans either ran stores or were farmers, but we all went to school together and church together and played on the same (sports) teams.”

Growing up in the hotel trade also shaped the approachable style he would later bring to politics. “In that business, you serve everybody, and as long as they’re paying their bills and aren’t causing problems, you don’t question them,” he says.

Summers was active and outgoing in high school, serving on the student council, Key Club, student advisory board, and as homeroom officer and captain of the basketball team. (He is 6 feet 4 inches tall.) He ran for class president his senior year, but lost in what his yearbook described as a close race.

“He was a good kid growing up, involved in sports, and a bit of a leader when he was in high school,” recalls Schwerbrock, who, like many people in town, has followed Summers’ rise in Maine politics, including his selection (by Republican legislators) to secretary of state, which is a very prominent, popularly elected position in Illinois.

“He’s probably one of the only people coming from Kewanee who has done that well in something political, ever,” says Clarke, who has covered Summers’ career for the local Star Courier newspaper since 2004. “People around here are proud he’s become secretary of state, and that somebody from Kewanee has become secretary of state of someplace!”

In 1978, when he graduated from high school, Summers says he had no interest in politics, and assumed he would spend his career in hotel management. He attended the local community college and, in 1980, transferred to the leisure studies program at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign.

MIDWEST TO MAINE

He says he also considered joining the Marine Corps, but instead met his future wife, Debra Draper, a doctoral student from Ontario who’d been educated in Switzerland and Canada. Instead of signing up for basic training at Quantico, Va., he would find himself in Maine, where Debra had been hired as a professor in the University of Maine’s health, physical education and recreation department.

Mainers don’t tend to think of Bangor, circa 1983, as having a thriving economy, but that’s what it looked like to the 23-year-old from Kewanee.

“It was really kind of a move up in the sense that in the Midwest things were stagnating and small towns were falling by the wayside,” Summers recalls. “And I went up to Bangor and there was a lot going on in terms of business and development. I really enjoyed it.”

He and Debra got married, and he took a job as the assistant manager of the Bangor Motor Inn. The first of their two children, Patricia, was born there. Charles III would be born in the Portland area, where the family moved in 1987, when Debra was hired by the University of New England in Biddeford. Charlie Summers stayed with the same company, which had recently opened a motel near the Maine Mall and is now a Day’s Inn.

In 1990, Summers decided to try going into business for himself. His father offered him Hotel Kewanee, but he was in love with Maine and not eager to return home. Instead, he opened a convenience store and bottle and can redemption center in Biddeford, Charlie’s Beverage Warehouse. He sold it a year later.

In 1990, he also became engaged in politics, running against Peter Danton of Saco — a seven-term Democratic state senator — for an open state Senate seat in the Scarborough area.

“I had been in town for maybe 2½ years, and of course they had never elected a Republican from that district,” Summers says. “I found out pretty fast that you couldn’t raise money and nobody would take you seriously, so I did what I could. I put some signs in the back of my truck and I knocked on doors on one side of the district, and my wife took the kids and went to the other side.”

He won by just over 600 votes, exciting the state Republican leadership.

“He was a new face, that’s what it was, unlike now, where he’s been around the block a few times and hasn’t been successful,” says Danton, who is friends with Summers, despite having lost to him again in 1992. “I probably went to the well for water too many times.”

Summers found Augusta exciting, even while working day jobs as a real estate agent and behind a car rental desk at the Portland International Jetport. “Suddenly you find yourself in the Legislature and the Senate and you’re in with the governor and everything else,” he recalls. “For a while I was like: Wow!”

In the Legislature, Summers was best known for joining 12 Republican colleagues in forcing a contentious 1991 government shutdown to force reform of the state’s workers’ compensation system. (Democrats controlled the Senate, but at the time, the state budget needed a two-thirds majority to pass.)

“It was a very high-stakes gamble, and I was a freshman legislator representing a Democratic district,” he recalls. “But clearly jobs and businesses were leaving the state, in part because the (workers’ comp) costs were suffocating business.” After eight days, a compromise was reached that Summers argues reduced costs and saved jobs.

He also backed an unsuccessful 1994 initiative by Gov. John “Jock” McKernan to slash income taxes by 20 percent over five years, which Democratic opponents characterized as a “rich man’s giveaway bill.”

“Who is it that creates jobs in this state?” Summers asked the Bangor Daily News at the time. “If this is something that offers a tax break to someone who is wealthy and that person in turn spends that money in our economy, then I say that is good.”

“My recollection is that Summers was widely regarded at the State House as a consistently pleasant, always even-tempered guy who got along well with everybody, although I don’t remember any noteworthy legislative accomplishments,” says retired journalist Paul Carrier, who covered the State House for the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram. “The more sarcastic ‘wags’ saw him as an empty suit and took to calling him ‘Jock lite’ because he was seen in some circles as a lightweight version of McKernan: gubernatorial-looking, like McKernan, but lacking McKernan’s substance, experience and political smarts.”

In this period, Summers also served on the national Republican Party’s platform committee, where he joined an unsuccessful 1992 effort to get the platform changed to reflect the position of pro-abortion rights Republicans like himself.

FAILED CAMPAIGN, PERSONAL TRAGEDY

In 1994, he stepped down from the state Senate to run for U.S. Congress, but lost the primary to Jim Longley Jr., the first in a series of electoral defeats.

“I think it was a challenge and an opportunity to serve,” he says of his three congressional runs. “When you are in Augusta or Washington, to be involved in something that’s bigger than you and to play a productive part in it, that’s something that drives me in this.”

That December, fellow Republicans nominated him for secretary of state at a time when the Legislature was almost evenly split between the parties. Ultimately, Windham Democrat Bill Diamond came away with the position.

Summers had worked closely with McKernan and in early 1995 secured a job with his wife, Sen. Olympia Snowe. He would serve as her state director for nine years. She would be an important force in his life for the next 17 years, helping him with his subsequent electoral campaigns, with his professional career and a personal tragedy.

In 1995, he joined the Navy Reserve and was trained as a public affairs officer. He was 36 with two young children, but the Cold War was over and Summers acknowledges it seemed unlikely that he would ever be activated for an extended period.

His first assignment for his “two weekends a month, two weeks a year” commitment was as an information officer in Boston. “It was great. You go to Boston and you get to be down there in the summertime with your white uniform and the wintertime in your blue uniform,” he recalls. “There were just great people down there who were associated with the unit over the years.”

In January 1997, Debra Summers was killed in an automobile accident while driving home from UNE. Her vehicle was discovered a day later, upside-down in a brook.

In the years that followed, Summers continued serving as Snowe’s state director while raising two children and serving in the Guard. (He has said that Snowe, whose first husband also died in a tragic car accident, helped him get beyond the tragedy.) He considered leaving military service, but was talked out of it by a colleague he met at a conference of Navy Reserve public affairs officers in Washington. He would marry that colleague, Ruth Rayburn, in 2002.

Today, the couple have a young child of their own. Since moving to Maine, Ruth Summers has also become a public figure in her own right. She replaced her husband as state party vice chair in 2010. Until earlier this year, she was executive director of the Education Management Corp.’s Education Foundation, whose corporate parent was headed by McKernan and is currently battling two whistleblower lawsuits alleging fraud, one of which is being represented by the U.S. Justice Department. Ruth Summers is chair of the board of the proposed full-time virtual charter school managed by Connections Academy of Baltimore. She is also currently running for the state Senate.

BALANCING MILITARY AND PUBLIC SERVICE

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks, Summers’ public affairs unit would be repeatedly activated. Two months after an airplane struck the Pentagon, Summers was working in the building that houses the office of the Navy secretary. From July 2007 to May 2008, he was deployed to Iraq as part of the Multinational Forces Iraq Strategic Effects Directorate. From October 2009 to October 2010, he served on the staff of Adm. Mike Mullen, then chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The deployments complicated his professional and political careers, causing him to drop one job and, later, to try to run for Congress while in Baghdad.

He stepped down from Snowe’s office to make a second run for Congress in 2004. He won the primary, but lost the general election to incumbent Rep. Tom Allen by 20 points.

In the aftermath of the election, Snowe backed Summers’ successful application to become the Small Business Administration’s New England regional administrator.

While there, Summers expressed support for George W. Bush’s tax cuts, which he said gave small businesses resources to invest in new equipment. He also argued that the biggest challenge facing the region’s small businesses was the high cost of health care, and said he would work to expand coverage.

“It was a fun job because you could measure what you were doing. If you helped person X get an SBA loan, you saw their business being opened and you could drive by and see the progress,” Summers says. “It wasn’t abstract.”

He resigned from the administration in June 2007 after his Reserve unit was again called up and deployed to Baghdad’s Green Zone. Although heavily fortified against ground attack, the area was subjected to rocket and mortar attacks from surrounding neighborhoods. The attacks were especially nerve-wracking when they occurred at night, when Summers was sleeping in their metal two-man residential trailer — or “hooch” — which would offer no protection from a direct hit.

His roommate, Michael Street of Kileen, Texas, recalls Summers being cool under fire.

“One of the things that struck me about him as a fellow Christian is that he is a man of faith,” he says. “You could tell people who have it and people who don’t. When the rockets start falling and the stress levels go up, he was consistent, never shaken, never too wound up by anything.”

Street was also struck by Summers’ sociability. “He’s never met a stranger, and it was pretty funny watching him interact with the troops,” he recalls. “We had Peruvians and Ugandans and Italians and Australians, and Charlie just had a way of connecting with everyone and from every walk of life. It was pretty cool to watch him lighten people’s day.

“Charlie’s not the sort of guy who wants to alienate one group or another,” adds Street, who later came to Maine to campaign for Summers. “He’s a guy you love to be around and who loves the state of Maine.”

Before leaving for Iraq, Summers had launched a third bid for Congress, but was prohibited by federal law from campaigning until he returned stateside. He has said that Ruth convinced him not to drop out, and she ran his campaign in his absence. He won the primary, but ultimately lost to Pingree 55-45.

In the 2008 campaign, Summers emphasized the need to encourage alternative energy development and to exploit domestic oil reserves. He supported a $10,000 tax credit for those purchasing hybrid vehicles and called for a federal effort to achieve energy independence comparable to the Apollo program. “The sooner we’re off foreign oil, the better we’ll be,” he told reporters.

Less than a year after the election, Summers was called up again. During his tour with Mullen, he spent several weeks with a Special Forces unit in Afghanistan, and was even caught in a firefight. He says such experiences put things in context.

“Do we have problems in Washington? Yes, but let’s look at what’s important here,” he says. “At least for me, it’s more about service to country than service to party.”

SOME CONTROVERSIAL STANCES

Shortly after his return from duty, voters gave Republicans control of the State House for the first time in decades. In December 2010, Republican legislators elected Summers secretary of state, a constitutional position that he holds today and that has oversight of elections.

His most high-profile act as secretary of state was controversial: an election fraud investigation of the 206 out-of-state college students on a list given to Summers by state Republican Party Chairman Charlie Webster. Although Webster held a news conference after delivering the list, investigators were unable to find a single instance of voter fraud by the students. Summers then sent letters to some of the exonerated students suggesting they might still be in violation of state law for not having registered their cars.

“Engaging in this hunt for students at the request of the chair of one of the political parties created at a minimum the appearance of impropriety that did more damage to our elections system than any student voter ever has,” says Zach Heiden of the American Civil Liberties Union of Maine, which represented the students. “The students, a number of whom contacted us, took (the follow-up letter) as a threat that they would get in trouble somehow if they voted.”

In 2011, Summers declined to endorse Snowe, who was then running for re-election against little-known tea party-backed challengers. He said such an endorsement would be a conflict of interest with his official position, an explanation that didn’t wash with some critics. The failure to endorse has caused his mentor to give him the cold shoulder since, and Snowe has told reporters she won’t donate to his campaign as a result of the incident.

“He owed a lot to her, and I think it speaks to character that he refused to support her,” says political consultant Ted O’Meara, a friend and former staffer to Snowe. “I think it was taken as a real slap in the face.”

Summers says he greatly regrets the situation, but that it is a result of a misunderstanding. “My concern was that by using my office — when you’re the chief elections official, would not have been good for my office and would not have been good for her,” he says. “I have supported her and I think the world of her and I hope we can bridge the gap that may or may not be there.”

But University of Maine political scientist Mark Brewer says that explanation doesn’t hold water. “Charlie Summers hasn’t seen fit to recuse himself from his secretary of state duties when he’s running for office and his wife is running for office,” he says. “If you’re not troubled by that, you can’t be troubled by endorsing Snowe.”

When Snowe announced she would not seek re-election this February, Summers decided to make another go at federal office. He won his party’s primary in June.

Political observers say he has run to the right of his previous stances, especially in emphasizing his belief that humans are not behind climate change and his embrace of conservative activist Grover Norquist’s anti-tax pledge, which would prohibit him even from eliminating existing tax breaks and loopholes. “He may feel he is in the same place ideologically that he always has been, but the issues on which he has chosen to focus certainly have shifted,” says Jim Melcher of the University of Maine Farmington.

Summers says he’s the same candidate as always, and points out that he’s also attacked as allegedly being a Republican In Name Only.

“It doesn’t matter who we sent to the Senate, whether it was Bill Cohen or George Mitchell, they took responsibility to move things forward,” he says. “That’s the approach that I take to this.”

Staff Writer Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at: cwoodard@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story