WASHINGTON – Mitt Romney’s former private equity firm used a half-dozen companies and partnerships in the tax havens of Luxembourg, Ireland and the Grand Caymans four years ago to channel $689 million in loans to a U.S. company that it co-owned.

To the average American, the deal might seem bizarre.

But some tax experts say that the circuitous paper chain likely was structured to avoid certain taxes for passive investors, including blind trusts for the Republican presidential candidate and his wife.

It’s just one of a maze of transactions involving the Romney family portfolio that were engineered in tax-neutral nations. The gradual emergence of outlines of these deals in recent weeks is prompting some experts to challenge Romney’s pronouncement that his scores of offshore investments haven’t lowered his federal taxes by so much as a dollar.

“It appears likely that offshore entities helped his investments avoid taxes or adverse tax consequences,” David Miller, a prominent New York tax attorney, told McClatchy Newspapers.

The New York Times reported Tuesday that it obtained documents showing that an offshore fund in which Romney’s investment retirement account held an interest probably used a “blocker” – an intermediary company that legally insulated the White House hopeful from paying 35 percent in taxes.

The release of documents from entities set up by Bain Capital Inc., the firm that Romney ran from 1984 to 1999, also are lifting a shroud from the dizzying world of private equity, an industry that has racked up huge profits with help from a small army of tax attorneys. Critics say these firms have found ways to exploit gaps between U.S. and other countries’ laws to deprive the U.S. treasury of billions.

The offshore deals are generally considered legal, typically structured to shield pension funds, foundations and other tax-exempt organizations from U.S. taxes, and foreign investors from U.S. taxes or taxes in their own countries. The California State Teachers’ Retirement System, for example, has since 2006 invested more than $500 million in three of the funds in which Ann Romney’s trust holds a stake.

Bain said in a statement that it must navigate complicated international tax treaties and tax codes for its clients.

“So, like virtually all global asset managers, we use widely accepted, fully legal and recognized structures so that investors may receive predictable tax treatment on investment gains for their constituents,” the statement said.

Even indirectly, Romney benefited. Whenever Bain’s strategies reduced taxes for a fund, he reaped returns because his 10-year retirement package gave him a slice of the management fees and profits from Bain Capital deals. The lower the taxes, the bigger the returns for each partner.

Because of the secrecy surrounding tax filings, no hard proof has surfaced that the Romneys actually realized any tax breaks from their offshore dealings. Such opaque rules leave tax experts making educated guesses.

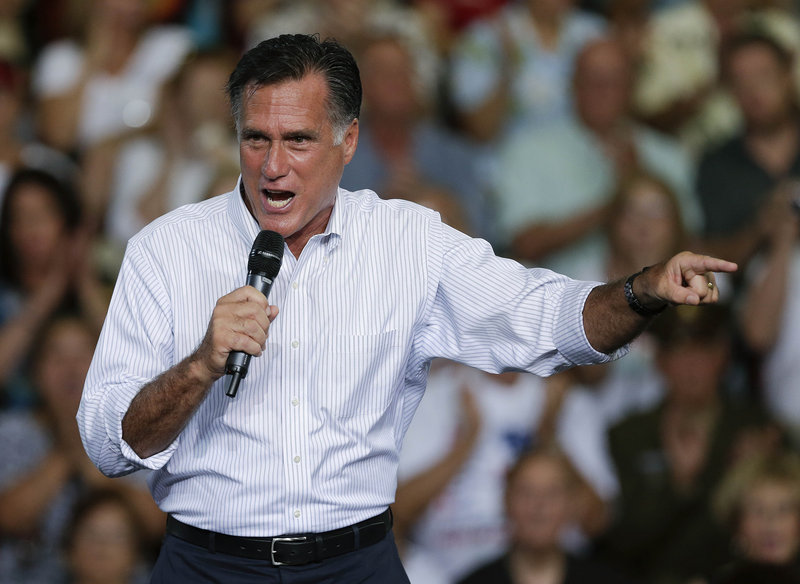

Romney, whose tenure as Bain Capital’s chief executive helped him amass a fortune worth up to $250 million, has refused to release enough financial data to definitively settle the touchy question of whether he got offshore tax reductions.

The issue of how much he’s paid in taxes while piling up all of that money and his refusal to release more than two years of his personal tax returns have dogged him for months and could come up Wednesday night when Romney meets President Barack Obama in the first of three presidential campaign debates.Miller, the tax lawyer, has reviewed Romney’s 2011 tax return and evaluated what’s public about some of the offshore deals. He’s found several instances in which evidence suggests Romney got tax breaks, including for his individual retirement account.

Miller’s assessment is at odds with Romney’s campaign. Michele Davis, a spokeswoman, said in a statement that “investments by the blind trusts in funds established outside the U.S. are taxed in the very same way they would be if the shares were held in the U.S.”

“No taxes are evaded or reduced,” Davis said. “These funds are all registered with the IRS (Internal Revenue Service) and report all income to investors and the IRS, just like domestic funds.”

By definition, private equity funds have few public reporting requirements, so obtaining financial statements from some of the offshore companies doesn’t definitively reveal what taxes might have been avoided.

Details of the Romneys’ offshore investments are evidenced in the couple’s recently released 2011 tax returns, the GOP presidential nominee’s financial disclosure statements, a trove of internal Bain documents posted by the Internet site Gawker.com, and filings in Luxembourg and Ireland obtained by McClatchy. As of Dec. 31, 2011, Romney and his family had as much as $50 million or more invested abroad, according to his disclosures. His extensive offshore investments have drawn scrutiny for multiple reasons:

• Romney pioneered Bain Capital’s offshore strategies, forming partnerships and companies in the late 1990s in Bermuda, the Grand Caymans and Luxembourg that helped spawn a system now criticized for minimizing tax revenue.

• By refusing to release more than two years of his tax returns, fewer than most party nominees in recent presidential elections, Romney has fueled suspicions that he has something to hide, perhaps related to his offshore investments.

• Documents released to date have enabled Democrats to paint the former Massachusetts governor as an aristocrat who’s capitalized on tax loopholes out of reach for average Americans.

“We’ve never had a candidate like this before, that’s for sure, who had all this stuff, the foreign companies and bank accounts,” said Daniel Shaviro, a law professor specializing in tax policy at New York University. “I admit I’m in many ways not sympathetic to his candidacy, but it does really raise questions about his thinking and about his values.”

Jack Levin, a Chicago attorney who has worked for dozens of private equity funds and teaches tax law at Harvard University and the University of Chicago, takes strong issue with such criticism.

“I’m just shocked that people say, ‘Just because you’ve had a fair amount of success, Mr. Romney, and then you want to run for office, you should be lambasted for having complied with the law over the 30 years (in which) you’ve had a fair amount of success,’ ” he said. “That just drives every successful person out of running for office. I think it’s unfair to criticize them for doing what’s permissible.”

Levin, a tax policy adviser to Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign but undecided about his presidential vote this year, said he has performed legal work for Bain Capital, but not in the last dozen years. He said he doesn’t know details of the deals in question. His firm, however, still works for Bain, and its members are among leading donors to Romney’s campaign, having given at least $393,667, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics.

Among the transactions that are piquing interest are those flowing from Bain’s purchase of ownership interests in two U.S. chains, the arts and crafts retailer Michaels Stores and HD Supply Inc., Home Depot’s former home improvement supply arm, whose sales were being hurt by a sharp downturn in the housing market when it was acquired in 2007.

In each case, Bain Capital and its co-owners later bought back debt at a fat discount as those companies struggled for survival.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story