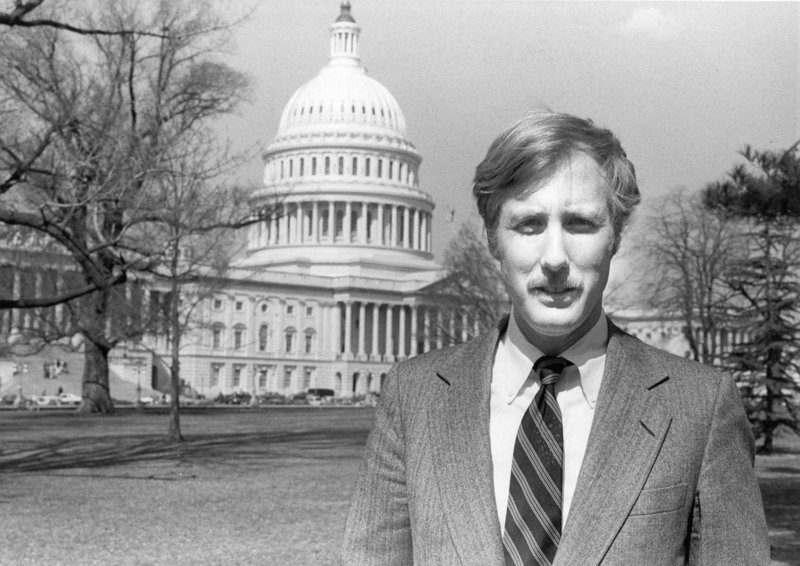

ALEXANDRIA, Va. – On Capitol Hill in the late winter of 1975, a young, idealistic Senate aide named Angus King had a political epiphany while studying a bill on behalf of his boss, Democratic Sen. Bill Hathaway.

The bill, introduced by liberal lion Walter Mondale of Minnesota, was written in response to the drowning of a 15-year-old YMCA camper during a poorly planned canoe trip on the West Branch of the Penobscot River. But it contained measures King thought would devastate summer camps across the country, including rural Maine, where he had spent several years providing legal aid to the poor.

“It got down to how many latrines you had to have per camper and that the path to the waterfront had to be paved with a certain kind of paver, and I thought this is just stupid,” he says of the sweeping safety regulations proposed in the bill, which prompted his break with Democratic Party orthodoxy. “I can almost date it from that moment, where I thought: The federal government and regulation is not the answer to everything. There are countervailing values.”

It was one of several turning points in King’s political evolution, marking an arc that carried him from being an idealistic young social activist in the tumult of the 1960s to a fiscally conservative, socially liberal two-term governor of Maine. Today, King is the front-runner in the race for the U.S. Senate, appealing to what he hopes remains a moderate majority in the center of Maine’s electorate.

His record as governor and businessman and his positions on the issues are being parsed as the campaign unfolds and voters decide whom to support. But his view of the world was shaped long before he ever ran for public office and will continue to inform the choices he would make if elected to the U.S. Senate.

PERSONAL PHILOSOPHY

A charismatic leader since his teens — at 17 he was elected “governor” of Virginia at the model government program, Boys State — King’s life turned at several points: the arrival of the civil rights movement in his home state and public high school; a brush with mortality at 29; and when the business startup he staked everything on took off.

A cancer survivor by age 30, a multimillionaire at 48, King has worked with the legal activists who ended debtor’s prison in Maine, on Capitol Hill for a Democratic U.S. senator, and within a succession of green energy businesses, including one he founded and whose sale gave him the freedom and resources to pursue statewide office.

By that time, he had developed a personal political philosophy, one he says seeks to improve the lives of poor, working and middle-class people, but his approach has often put him at odds with one party or the other.

“I am uncomfortable with the Democrats because their first line of defense is regulation, tax the rich, government is the solution,” he says. “I part company with where the current right wing of the Republican Party wants to go because we don’t have to speculate on what an unbridled, unregulated economy looks like: We lived it. You had women and 12-year-olds working 16 hours a day at the Cabot Mills.”

A generation ago, a person with King’s views might have fit comfortably into the centrist wings of either party, but in today’s more polarized political climate, he is a man without a party, seeking admission to a highly partisan legislative body.

“My philosophy is: I call ’em as I see ’em and do what works,” he says, though he admits his philosophy was some years in the making.

ROOTS OF INFLUENCE

King was born in 1944 in Alexandria, Va., on the banks of the Potomac just southeast of Washington, D.C., the first son and youngest child of a family with deep roots in that city.

Most of his great-grandparents are buried in the city’s cemeteries. His maternal grandfather had been mayor during the Great Depression, an office one of his aunts would hold in the 1990s. An uncle served on the city council while Angus was in grade school and was later chief clerk of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

His father, Angus Sr., was a U.S. magistrate judge and would serve at one time or another as chairman of the city’s school committee, Rotary Club and local theater. King and others have described him as a Southern gentleman: mild-manered, courtly and principled. He had met Angus’ mother, public school teacher Ellen Ticer King, at the College of William & Mary.

“People erroneously assume that he came from money,” says King’s first wife, Edie Birney, who knew her in-laws well. “They were community leaders. They were respected, but not moneyed.”

King grew up in a comfortable brick two-story home in a leafy new neighborhood on the slope of Seminary Hill on the outskirts of town.

The main gate to the Virginia Theological Seminary — the U.S. Episcopal Church’s largest — was literally across the street. It had been founded in the early 19th century by the leaders of St. Paul’s Church downtown, where King’s parents had been married and served on the vestry while his mother was president of the Episcopal Church Women of the Diocese of Virginia. King has said that if his mother had been born a generation later, she would have become an Episcopal bishop.

“His father was really a very dear man and a steady churchgoer, and his mother was very much a leader in the church, and looked like Queen Victoria,” recalls Birney, who was raised in the Episcopal Church outside Hanover, N.H., and met King when he was studying at Dartmouth College. (She is now a church deacon and married to an Episcopal priest.) “He’s steeped in the church.”

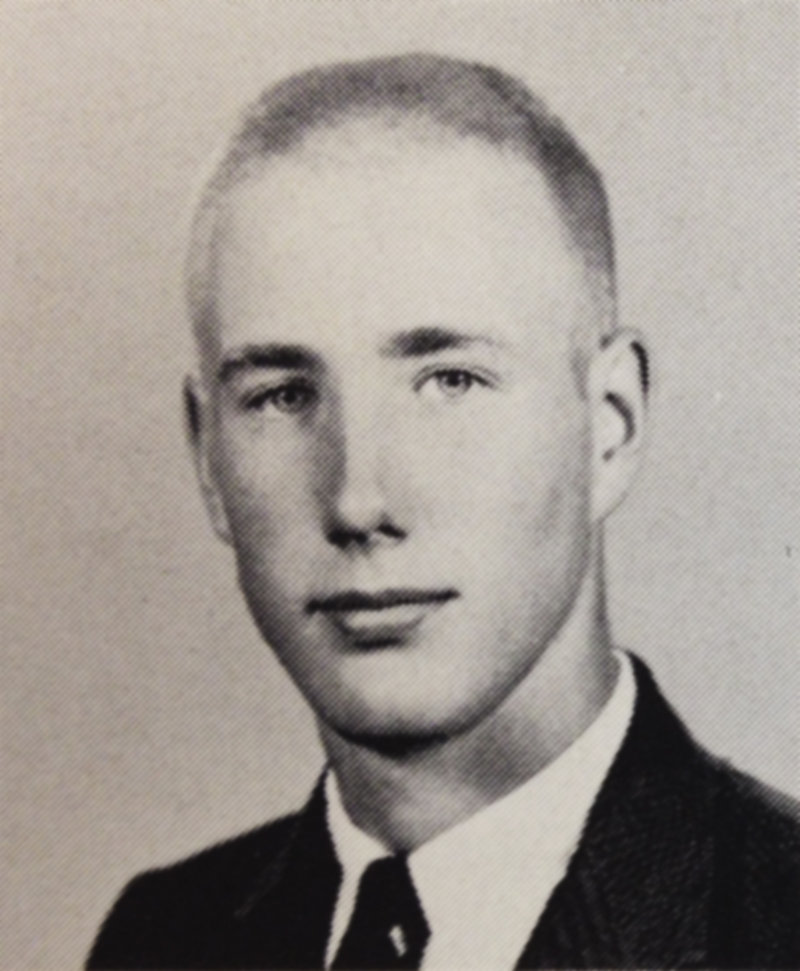

He attended Hammond High School, where he played football as a defensive back and was elected president of his junior and senior class. He was a 1961 delegate to the American Legion’s model government program, Boys State, where his peers elected him “governor” of Virginia. (At the time, The Washington Post ran a photo of 17-year-old King being congratulated by Virginia’s actual governor, J. Lindsay Almond.)

King also served on the three-student championship team in the inaugural season of “It’s Academic,” a television quiz show that is still on the air and is one of the longest-running in broadcast history.

“Everybody knew who Gus was, and we assumed he wanted to be a politician,” says classmate George M. Williams Jr., one of King’s “It’s Academic” teammates. “He was a natural-born leader of that sort and had the ability to get people to work with him on a cooperative basis without looking like he was getting them to work for him. He didn’t have to expend effort or advertise himself to do this.” Asked if he was surprised that King became a governor and is now a U.S. Senate front-runner, Williams said no. “That kind of thing we would have expected of him,” he added.

FORGED BY CIVIL RIGHTS

King says his first political awakening came in 1959, during his freshman year of high school, when a federal court forced Hammond to become the second high school in Virginia to integrate. Thirty policemen surrounded the school as federal marshals led Patsy Ragland, 14, and her 13-year-old brother, James, into the school. In the foyer, the two black siblings found themselves standing in silence amid a semicircle of 200 to 300 curious, uncertain white students.

“It was absolutely silent, and nobody knew what to do,” recalls King, who was in the crowd. “After this long pause there was a voice saying, ‘Excuse me, excuse me,’ and it was Mike Vopatek, who was senior class president, captain of the football team, and went on to West Point. He didn’t make a speech or anything, he just came up to the Raglands and said, ‘Hello, I’m Mike Vopatek, can I help you find your class?’

“That moment could have turned ugly, but that set the tone and defused the moment,” he says. “I’m a great believer that we have better and worse angels of our nature. We can be led in either direction, and leadership is so important. People can be moved to be generous and tolerant and all those things, and can also be moved to be hateful.”

Alexandria’s integration went relatively smoothly. But in other parts of Virginia, segregationists engaged in “massive resistance,” with some counties closing all public schools entirely for months and years on end rather than integrate. “That was too much for my dad,” King recalls. “To him, public education was the linchpin of democracy, so he became an activist.”

King became an activist of a sort himself. While home from Dartmouth in the summer of 1963, he joined the crowds converging on the National Mall to hear Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his now-famous “I Have a Dream” speech. While attending law school at the University of Virginia, he was campus coordinator for Sen. Bobby Kennedy’s presidential campaign until the candidate was assassinated. He also joined the Legal Aid clinic, which dispatched students to the surrounding countryside to prepare cases for poor, unrepresented clients.

“We were pretty inexperienced, but in this particular area of the South there hadn’t been any lawyers actively working on behalf of poor people in any way,” says one of King’s fellow law students, Michael Fox, now a retired judge in Seattle.

“I remember talking to one local official who said, ‘We have some pretty successful policies here, like if somebody has more than three children in this county, we make the women get sterilized to get welfare benefits,'” he says. “My jaw just dropped. Totally illegal, but nobody was there to challenge it.”

“Civil rights was an important, formative part of my life, because as Bob Dylan sings, it was all that easy to tell wrong from right, all you had to see was black from white,” King recalls. “It was pretty clear: MLK was the good guy and Bull Connor” — the police chief who turned dogs and firehoses on peaceful marchers in Birmingham, Ala. — “was the bad guy. There was a kind of moral certainty that young people are always looking for. Only when you get older do you realize that it’s more complicated.”

IN MAINE: DEBTORS, DOMES

Like many of his peers, King did a summer internship with one of Washington’s corporate law firms, but shocked his mother by not applying for a job at graduation in 1969. Instead, he secured a Legal Aid fellowship and was given three choices: Maine, Louisiana or a Sioux reservation in South Dakota. His Yankee bride lobbied for Maine because of the similarities to western New Hampshire, where they’d met. (Bizarrely, one of his would-be Legal Aid colleagues in South Dakota, Bill Janklow, later became that state’s governor.)

Together, the Kings moved to a town he’d never set foot in — Skowhegan — where he was assigned to the staff of Pine Tree Legal Assistance. They would live three years in the Skowhegan area, where their son Angus III was born and where they built a Buckminster Fuller-designed geodesic dome as a weekend cottage.

In western Maine the young lawyers encountered situations nearly as shocking as those King found in central Virginia. In Farmington, they discovered people were being interned in debtors’ prison. “It was a total dungeon at the time, really cold and dank, and there was this guy who was there because he couldn’t pay his hospital bill,” recalls King’s colleague Michael Gentile, who successfully challenged the practice in court and is now a partner at the law firm Preti Flaherty.

“I thought this sort of thing had been done away with for 200 years, but here was Franklin County Hospital putting them in jail something regular,” he says.

Gentile recalls King as being idealistic, “but not as much as some of them. He wasn’t a firebrand or a bomb thrower.”

In a 1971 interview with the Bangor Daily News, King conveyed a mix of idealism and practicality, waxing poetic about the promises of the Declaration of Independence and later on the need to avoid “a we-they attitude toward the establishment” to be effective.

“We’ve run into a hornet’s nest representing people who’ve never been represented before,” King told the reporter. “We’re running up against interests which have had their own way for 500 to 600 years. They don’t like it when we throw a monkey wrench into their business.”

“It is interesting nationally that our two severest critics are the extreme right and the extreme left elements in our society,” he added. “The extreme right because we rock the boat and the extreme left because we make the system work.”

King says that in Skowhegan he began to see the limits of what Legal Aid could accomplish. “I remember having this conscious realization that people came into office with problems this big” — he stretches his hands far apart — “but their legal problem was this big” — he closes them to within six inches.

“I could deal with their legal problems, but I couldn’t deal with their lack of dental care, their lack of care for an autistic child, their total lack of education, all these other things,” he says. “It made me think: If you’re going to help people, you’re going to have to try to deal with a larger segment of who they are. So I went to work for Bill Hathaway.”

KING ON THE HILL

In 1972, King and his wife joined the campaign staff of Bill Hathaway, a Lewiston lawyer challenging Republican U.S. Sen. Margaret Chase Smith. King acted as Hathaway’s driver and, after their upset victory, as a staffer on the Senate Labor Committee in Washington.

King saw the Senate up close in those years, but it was a different place from what it is today. “There was a lot more comity then,” says Hathaway, a liberal Democrat who was close friends with conservative Republican Orrin Hatch. “Republicans and Democrats worked pretty well together. We had different views, but we managed to reconcile our differences in ways that were palatable to all of us.”

King counts Hathaway among his political mentors for the way he made political decisions. He recalls briefing the senator on a proposed measure to extend labor protection to fish cannery workers, and advising him, “If you vote for this, the women who benefit from it will never know, and the owners will hate your guts.” King recalls Hathaway writing back, “I pay you for policy advice, not political advice” and later telling him that if he’d ever seen the conditions in the canneries, he would have no doubt how to vote.

“He’s something like I am,” Hathaway says of King. “I voted the way I thought was the best way to go and if my constituents didn’t like it, I tried to explain it to them. If you’re just trying to vote the way your constituents want on every issue, you’re not being a leader and you shouldn’t be there.” (Hathaway lost his re-election bid to Rep. William S. Cohen in 1978.)

Another turning point in King’s life came in February 1974 when, at 29, he was diagnosed with melanoma, a form of cancer with a 50 percent survival rate. It had been caught early in a routine physical, and he made a full recovery after undergoing surgery at the National Institutes of Health. He says it’s why he supports the Affordable Care Act.

“Somewhere in this country is a grave of a guy who was situated exactly like me who didn’t have insurance or a checkup, and he’s gone,” he says. “So how can I say I deserve to be alive and that guy doesn’t? I just can’t abide by that.”

Birney says the cancer scare also brought them back to Maine. “There was this period of reflection that doesn’t usually happen when you’re in your early 30s: ‘Where am I going and what am I doing?'” she says. “The question was: ‘Do I stay and work on the Hill my whole life? Stay in Virginia and practice law?’ But we had both liked Maine and had good friends there, and we had two kids then and it just seemed like it would be ‘more family’ and more time for the kids. Politics wasn’t an angle.”

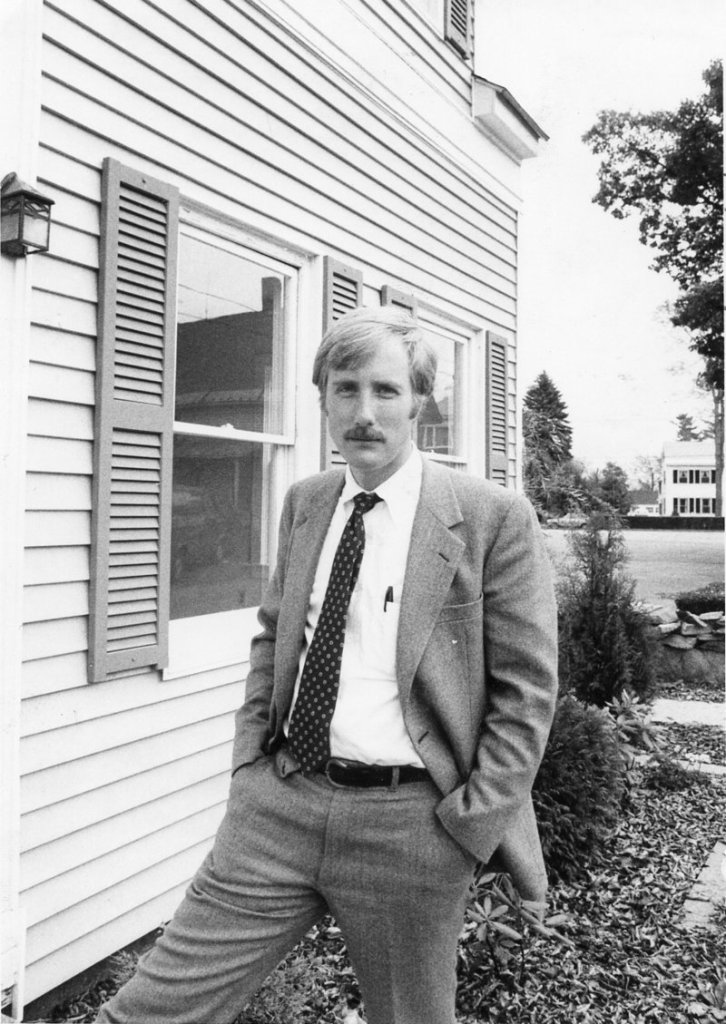

That summer, the Kings moved to Topsham. King started a law practice in Brunswick that struggled initially. He became host of the progenitor of public television’s “Maine Watch,” was an instant success and stayed for 17 years. Television satisfied his political itch — he had to immerse himself in a policy issue every week — while a mix of small-town lawyering and Augusta lobbying (for the National Resources Council of Maine, Maine Audubon, the cable industry and others) kept food on the table.

He and Birney were divorced in 1982, but have remained on good terms. “I happen to know that he’s highly moral and full of integrity,” says Birney, who supports his Senate run. “I can’t think of a better candidate.”

LAWYER TO BUSINESSMAN

King’s first foray into the business world came in 1983, when one of his clients hired him as vice president and general counsel. Swift River was the first of three alternative energy companies King would become involved in, and focused on rehabilitating or adding power plants at small-scale hydro dams. The company completed projects across New England but ran into controversy when it sought to refit an aging dam in Bangor. Regulators quashed the project to protect Atlantic salmon.

“I was told in that period to ‘quit ruining our rivers, why don’t you do windmills?'” King recalls. “Which is pretty bizarre because 20 years later I was doing windmills and people were saying, ‘Quit ruining our mountains.'”

But as power from other sources became cheaper, Swift River’s business model eroded. At a 1988 Christmas party, Swift River laid off 40 of its 44 employees, including King. He took a severance package that included the rights to a concept he’d been working on: selling conservation, rather than electricity, to utilities.

“The idea was if large users cut their usage, it left more power on the table for the utility to resell, as opposed to having to buy more,” King says.

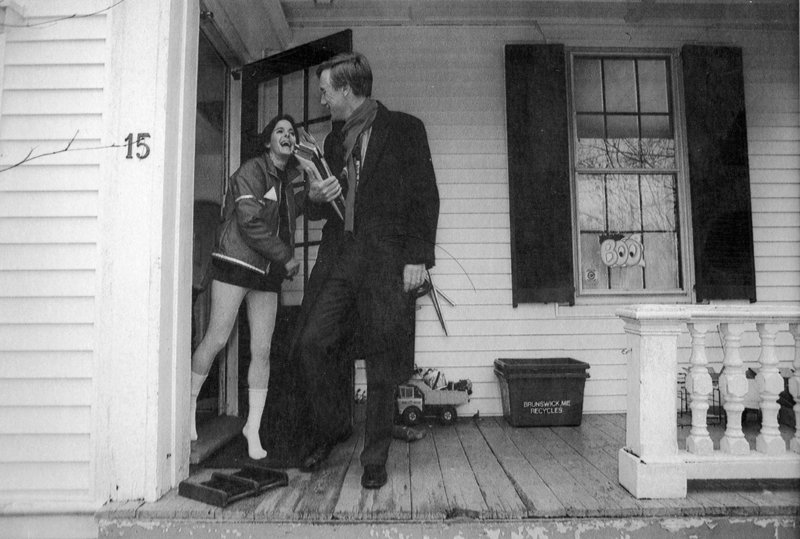

King says he gambled everything on the new business, taking a second mortgage on the house he owned with Mary Herman, former head of the Maine Women’s Lobby, whom he married in 1984. She had been a social studies teacher and family planning advocate, but was familiar with energy issues in her role as a lobbyist for Central Maine Power. His company, Northeast Energy Management, ultimately bid for and won a competitive CMP contract to sell the utility power savings at rates roughly a third to half the cost of having to buy the same power.

It was a win-win situation for the environment, the utility, King and the large power consumers. King’s company saved companies and institutions tens of thousands annually by upgrading inefficient lighting, blowers and other equipment. The utility avoided firing up generating plants with lower profit margins and higher carbon emissions. And Northeast Energy generated an ever-increasing revenue stream as more and more projects were completed.

“My concern wasn’t with what King was doing or the idea of the (CMP) program — which was a good idea — but that there wasn’t enough benefit to the ratepayers,” says Gordon Weil, an energy consultant and one-time public advocate who was critical of the deal. “Under the way it was structured, he was probably the principal beneficiary. He didn’t do anything wrong, but I think he got too much money out of this compared to what the customers got.”

King sold the company in January 1994 to a Massachusetts-based competitor and personally netted $8 million after taxes. Suddenly, King had the wealth and time to do whatever he wished. He ran for governor as an independent.

GOVERNOR AND BEYOND

King had briefly considered a run for Congress in 1986, but dropped the idea when former Gov. Joseph Brennan announced he was running. “I’d always been interested in politics and expected to be involved, but it just didn’t happen because of children and a young family and I kind of gave up on the idea,” King says. “Then all of a sudden all the stars were in alignment.”

The next decade of King’s life is relatively well-known. Capitalizing on public dissatisfaction with partisan dysfunction in Augusta (there had been a state government shutdown in 1991), King defeated Brennan and a little-known Republican, Susan Collins, in a tight three-way race. While governor he at one time or another irritated liberals by vetoing minimum-wage increases and social conservatives by backing gay rights initiatives. The economy was booming for much of his tenure. He was re-elected in 1998 by a 40-point margin.

“Angus came along at exactly the right time and was exactly the right person,” says Colby College government professor Sandy Maisel, a Democrat who has donated to King’s Senate campaign. “There was a great deal of dissatisfaction with government and partisanship, and Angus then and now had a nonconfrontational nature that was appealing and what the state was looking for.”

“He calmed the waters — which was not trivial — but I don’t think his second term held up to his first,” he added.

“There were efforts to trim back spending in the first two years of his first term, but after that as far as I could see the Democrats who ran the Legislature passed their budgets,” says Jon Reisman, a libertarian-minded economist at the University of Maine at Machias who worked in King’s administration, but supports Charlie Summers. “He was never dishonest about the fact that he was for an activist government in some areas, particularly environmental policy. But there was this subtext in ’93 and ’94 that he was for less government, and I think he left that behind.”

“King successfully and consistently pushed a positive message and an upbeat outlook that made Mainers feel good about being Mainers,” says retired journalist Paul Carrier, who covered the State House for the Portland Press Herald for two decades. “King could be thin-skinned and controlling behind the scenes, but the public didn’t see that side of him, so it didn’t figure into voters’ attitudes.”

Immediately after his second term, King, Mary, and their young children Ben and Molly departed on a six-month cross-country road trip in their RV, a journey King wrote about in “Governor’s Travels.” They then returned to Brunswick, where he and Mary still live.

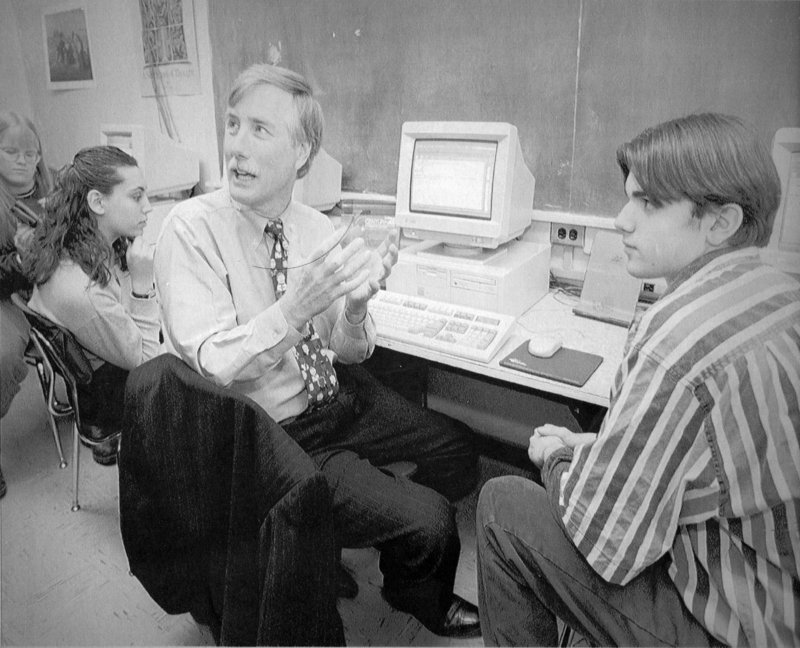

In the nine years since, King has taught at Bowdoin and Colby colleges and remained involved in both business and nonprofits. He has served or serves on the boards of the Nature Conservancy of Maine, Maine Policy Scholars, the Maine International Center for Digital Learning, Hancock Lumber, the parent company of Lee Auto Malls, Goold Health Systems, and the engineering firm Woodard & Curran. He became a director of the struggling Bank of Maine in 2010, after its unhealthy loan portfolio had drawn the ire of federal regulators. (He resigned to run for Senate.)

From 2004 to 2010, he was also on the board of W.P. Stewart, a Bermuda-based international investment fund whose namesake founder met King at a ceremony at East Boothbay’s Hodgdon Boat Yard, where Stewart’s 154-foot yacht was built. The firm struggled after Stewart’s retirement and the 2008 financial meltdown and was delisted by the New York Stock Exchange in 2009. King’s financial disclosures show he still has tens of thousands in a company mutual fund.

He’s been a partner in two business ventures. The first, Leaders LLC of Portland, helps companies sell themselves to larger competitors or vice versa, brokering a New Hampshire gas station’s sale to Irving Oil and helping Hancock Lumber purchase Brunswick’s Marriner Lumber.

The second, Independence Wind, aimed, in King’s words, to do wind energy right. The company built a wind farm in Roxbury that has strong community support but is disliked by the sector’s many critics. The firm received $100 million in loan guarantees from the same federal program that backed Solyndra, but unlike the failed solar firm, it is repaying its loans. King — whom Republicans have criticized for relying on taxpayer subsidies — has said he ultimately netted $212,000 from his six-year involvement with Independence.

“Wind development hadn’t been being done in the right way and was triggering more opposition than it needed to,” says Rob Gardiner, King’s partner in the venture. “Angus and I decided we wouldn’t have that problem because everything we said would be true and defensible.” He says they did that at Roxbury, but they still faced opposition because of the earlier sins of others in the industry.

King divested himself from the wind firm when he decided to take on a new project: running for the U.S. Senate.

Staff Writer Colin Woodard can be contacted at 791-6317 or at:

cwoodard@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story