AUGUSTA – Across the country, voters have banned or rejected same-sex marriage at the ballot box more than 30 times since 1998.

This year, as four states consider the issue, Maine voters will be the first in the nation to be asked by same-sex marriage supporters to approve it by popular vote. Until now, voters have been asked only to ban it or reject it.

The idea of being on offense for a change appeals to supporters.

“At some point, we are going to win one of these campaigns at the ballot box,” said Matt McTighe, campaign manager for Mainers United for Marriage. “I really do believe Maine will be that state.”

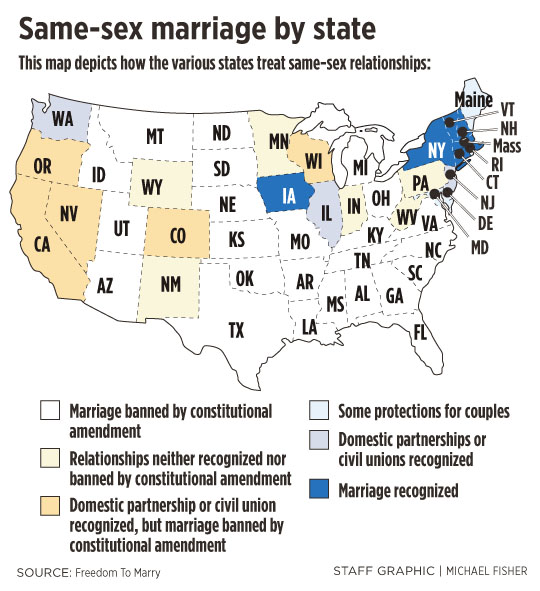

In the six states where same-sex marriage is legal, it’s because the courts or state lawmakers approved it. But in 31 states, there are constitutional bans, which makes it much more difficult for gay advocates to advance their agenda. That leaves just 13 states in play, and four of those states — Maine, Minnesota, Maryland and Washington — will vote this fall.

In Minnesota, voters are being asked to approve a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage, and if it passes, the Gopher State would become the 32nd in the country with such a ban. Maryland and Washington state voters will decide whether to repeal laws allowing same-sex marriage that were passed by their legislatures and signed by their Democratic governors.

While voters across the country have rejected same-sex marriage for 14 years, one national expert says what makes this year different is a shift in public opinion.

Jennie Bowser, a senior fellow at the National Conference of State Legislatures, points to a poll released in April by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life that shows 47 percent of Americans indicating support for same-sex marriage, with 43 percent opposed.

“The significant thing this year is the change in attitude as indicated by polls,” she said.

Bowser’s analysis of voting results shows that in 2005, nearly 70 percent of voters nationwide opposed same-sex marriage. By 2009, the opposition had weakened to 53 percent. But there’s plenty of room for variation: In the most recent statewide vote on the issue, North Carolina voters easily approved a constitutional ban in May with 61 percent support.

Carroll Conley, executive director of the Christian Civic League of Maine, said he learned some lessons while in North Carolina on the day of the vote.

“We were told they (same-sex marriage opponents) were really in trouble, and we weren’t just hearing it from the media, but from inside sources,” said Conley, who is helping to run Protect Marriage Maine, the leading opponent of same-sex marriage.

But the polls were wrong and the strength of clergy was underestimated, he said. After recently traveling Maine to meet with clergy, Conley is feeling good about the campaign in Maine.

“The advantage we have is the vast majority of clergy has an opportunity weekly to address this issue for the next 11 weeks,” he said. “That doesn’t cost us anything.”

While there are regional differences on the issue — Bowser’s analysis shows consistently stronger opposition in the South — Maine has a relatively recent history of voting on the issue as well. In 2009, Maine voters rejected same-sex marriage 53 percent to 47 percent.

The question on the ballot in 2009 asked voters: “Do you want to reject the new law that lets same-sex couples marry and allows individuals and religious groups to refuse to perform these marriages?”

Brian Brown, director of the National Organization for Marriage, which provided the bulk of the funding for same-sex marriage opponents in 2009, says the outcome in Maine will be the same this time around. He said same-sex marriage supporters have been effective in trying to claim that voters have changed their minds, but the outcome in North Carolina challenges that conclusion.

“It’s almost to the point of the theater of the absurd,” he said. “This same narrative is trotted out for every single vote.”

Brown’s organization will contribute to all four campaigns across the country this year, but it won’t be able to give as much to the Maine campaign as it did three years ago. That’s when NOM donated nearly $2 million to same-sex marriage opponents.

Despite his confidence in voters, Brown said he is concerned that same-sex marriage opponents in Maine won’t have a well-funded campaign. So far, same-sex marriage supporters have raised $1.6 million and opponents have only $77,850, according to the most recent campaign finance reports, filed in July.

Nationally, the debate over gay marriage will continue to play out in three arenas for the foreseeable future: the courts, state legislatures, and at the ballot box.

“We don’t anticipate any of those three fronts going away,” said Jim Campbell, a staff attorney for the Alliance Defending Freedom, a group of Christian attorneys who fight same-sex marriage across the country. “We see pro-marriage folks are focused on preserving marriage as the union of one man and one woman. Those seeking to redefine marriage will use all three avenues.”

In Minnesota, Republicans who took over the legislature for the first time in decades made a constitutional ban one of their big agenda items, said Larry Jacobs, a political science professor at the University of Minnesota. Although same-sex marriage is already against state law, supporters of the ban felt they needed to put it in the state constitution, he said.

“The folks opposing the constitutional amendment are very well organized and this is a real battle,” he said. “Supporters of the ban have an organizational infrastructure that puts feet on the ground all over Minnesota.”

Same-sex marriage supporters say they are worried that a constitutional amendment will delay by years any positive movement on the issue.

“It would theoretically shut down the conversation in our state,” said Kate Brickman, press secretary for Minnesotans United for All Families, the campaign to defeat the amendment. “From our standpoint, we are on the defensive. We didn’t ask for the debate, for sure.”

Conley, at the Christian Civic League, said he and other gay-marriage opponents in Maine have discussed the possibility of pursuing a constitutional ban here if they win this fall. That would require a supportive Legislature and governor, because citizens cannot bring state constitutional amendments forward by petition.

“I’m hopeful maybe we can win this again and hold the status quo and maybe go to the Maine people and say, ‘It’s time for a constitutional amendment,’” he said.

In Maryland and Washington state this year, voters will be asked to approve or reject same-sex marriage laws passed by lawmakers. It’s the same type of vote that took place in Maine in 2009, when voters repealed the law passed by Democrats and signed by then-Gov. John Baldacci, a Democrat.

In Maryland, Gov. Martin O’Malley, widely considered to be a possible presidential candidate in 2016, signed a same-sex marriage bill into law in March.

In Washington state, after dramatic floor debates in the House and Senate, Gov. Christine Gregoire signed a bill in February. Immediately, opponents in both states began gathering signatures to take the issue to a popular vote.

Evan Wolfson, founder of Freedom to Marry, a New York group working to bring same-sex marriage to every state in the country, said the “patchwork of progress” across the country will continue to play out in state-by-state battles.

“No civil rights movement wins in every state on the same day, and none of them happen overnight,” he said.

Susan M. Cover can be contacted at 621-5643 or at:

scover@mainetoday.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story