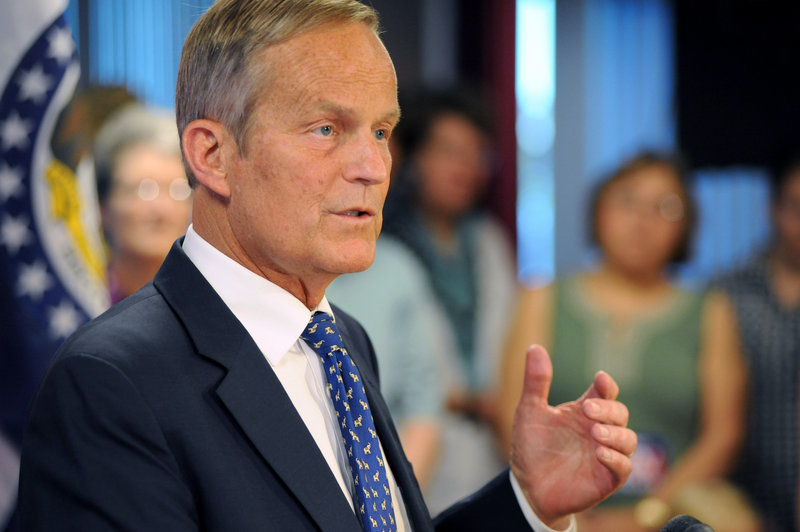

The voice of Rep. Todd Akin, R-Mo., claiming that women rarely get pregnant when they are the victims of “legitimate rape,” is now being featured in its first campaign advertisement of the election season.

But the ad is not on behalf of Democrat Claire McCaskill, whom Akin is challenging for a U.S. Senate seat in Missouri. Instead, it’s a radio spot airing in Massachusetts for Elizabeth Warren, who is challenging Sen. Scott Brown, a Republican.

“Just imagine if Republicans win the White House, or gain control of the U.S. Senate,” a narrator in the ad says after Akin’s now-famous remark.

As Republicans continue to attempt to salvage their chances of winning the Missouri race — a critical seat for control of the Senate — Democrats are hoping that Akin’s words will reverberate in other House and Senate races around the country.

Their efforts come as Akin remained defiant on Thursday, issuing a new promise to remain in the race. He spent Thursday meeting with social conservatives in Tampa amid signs that some leading public figures were rallying to his side.

Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, who backed Akin in his tough three-way primary for the Republican nomination, sent his supporters a lengthy letter criticizing Republican leaders for denying Akin assistance and urging help for him.

“From the spotlights of political offices and media perches, it may appear that the demand for Akin’s head is universal in the party. I assure you it is not,” Huckabee wrote. “There is a vast, but mostly quiet army of people who have an innate sense of fairness and don’t like to see a fellow political pilgrim bullied.”

That fissure, which could command significant attention at this week’s Republican National Convention, has complicated efforts by top Republicans to stem the damage from Akin’s remark with swift condemnation and a mass effort led by presidential candidate Mitt Romney to force him out of the race.

During a television interview broadcast last Sunday in St. Louis, Akin said that his opposition to abortion extended to cases involving rape and offered this explanation: “If it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down.”

He added that even if the woman became pregnant, “the punishment ought to be of the rapist and not attacking the child.”

The congressman has apologized for using the “wrong word,” but he has stood by his larger point that abortion should be illegal in all instances, including rape.

That has forced other GOP candidates to face tough questions about their own positions on abortion as local media outlets have highlighted Democratic efforts to pull Akin into their own races.

“A lot of districts we need to win this fall are suburban districts, and this kind of ideological extremism doesn’t play well there,” said Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee spokesman Jesse Ferguson.

Democrats believe the remark can provide Warren a particular boost. They are emphasizing to left-leaning Massachusetts voters who might find Brown appealing that a vote for him means backing a Republican majority in Washington.

Republicans hope Brown has fended off that attack by using the Akin incident to show his independence from the Republican establishment.

He was the first Republican to call for Akin to quit the race. He also wrote a letter to Republican National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus asking that he intervene to soften language adopted in the party platform last week that appears to endorse a constitutional amendment banning abortion without exceptions for rape or incest.

“All our candidates really got out ahead of this very quickly and prevented (Democrats) from scoring points,” said a top Republican strategist who would not be quoted on the record discussing internal party strategy.

But the Akin furor has not yet died down, and Democrats believe Akin could also affect Senate races in Wisconsin, Virginia and Florida.

Emily’s List, a group that supports pro-abortion-rights women running for office, has been highlighting Republican candidates whose voting record they say resembles Akin’s. They’ve focused on those who joined Akin in sponsoring a 2011 measure that, as introduced, would have banned federal funding of abortions except in cases of “forcible rape.”

The controversial “forcible” language was dropped by the time the bill passed the House; the bill did not pass the Senate.

The Akin incident could also reshape campaign spending patterns by political groups that had planned to be active in Missouri.

The National Republican Senatorial Committee had reserved $5 million to buy advertising time in Missouri, money that party leaders now say will not be spent on behalf of Akin.

That decision may free up those dollars for use in other Senate battlegrounds, including Florida, Ohio, Montana and Virginia.

Democrats, too, could find themselves with additional money to spend outside Missouri if contributions for Akin dry up, particularly since McCaskill has seen a fundraising jump since Akin’s comments.

Neither party has yet made a move. Republicans need not pay for their reserved time until ads begin airing. They will not relinquish the ad time for several weeks in case they need it to support an alternative candidate if Akin reverses course and drops out.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story