When Dana Connors got a call from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce last month letting him know the group was about to air a TV ad criticizing independent U.S. Senate candidate Angus King, the president of the Maine State Chamber of Commerce knew he was in a tough spot.

And not because Connors led former Gov. King’s transition team in 1995. The state chamber and the 60 local and regional chambers around the state generally try to stay out of Maine elections, partly because they have to work with whoever wins and partly to avoid alienating member businesses and their customers.

Connors, in fact, said he told the caller the ad might not be a good idea.

“You are criticizing one of our candidates,” Connors recalled telling the U.S. Chamber. “I’m concerned about that because it puts us into a political position that carries a negative (tone). We’re a state chamber. We live in the state every day. We’re concerned about our brand.”

The airing of the anti-King commercial and the endorsement of Republican Charlie Summers clearly created some tension between the national chamber and the state and local chambers in Maine. It surfaced again last week after the U.S. Chamber’s political director came to the state to campaign with Summers and criticize King in person.

While the groups share the same chamber identity — or brand — leaders of the Maine groups have been assuring businesses and consumers here that they are separate and independent from the more political national organization.

The Portland Regional Chamber, for example, posted a statement assuring members that none of its $400 in yearly dues to the U.S. Chamber helped pay for the anti-King ad. “We do not stand with or against any candidate,” CEO Godfrey Wood wrote.

Similar national ads aimed at candidates in New Hampshire and other states in 2010 led some local chambers to publicly end membership in the national group in protest. There has been no evidence of such an exodus in Maine, although there may yet be more to the story. The U.S. Chamber spent $400,000 to air the 30-second ad on every network statewide for a couple of weeks, including during the Olympics. If the U.S. Chamber sees King’s poll numbers drop as a result, it will likely spend far more before the Nov. 6 election, experts say.

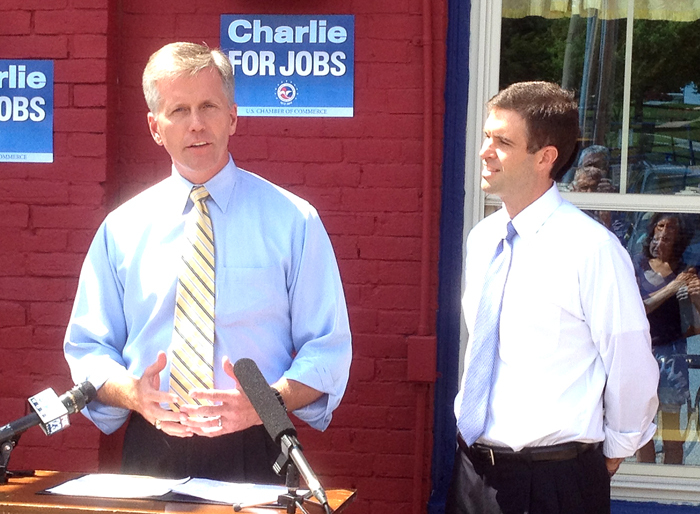

Rob Engstrom, the U.S. Chamber’s national political director, said during a campaign stop with Summers in Lewiston last week that the group was “encouraged by the results (and) some of the feedback from the ad.”

A poll commissioned by the Summers campaign suggested that King’s lead over Summers had dropped to 18 percentage points early this month from about 28 points in late June, but no independent polling has been reported to confirm that.

Engstrom did not promise more television commercials while in Maine last week, but he said the group was not pulling out of the Maine Senate race. “We’re going to continue to be aggressively involved,” he said.

Engstrom also defended the U.S. Chamber’s political activities in Maine and elsewhere. “It’s our First Amendment right to engage on behalf of our issues,” he said.

Maine is one of 13 states where the U.S. Chamber is trying to elect Republicans to the Senate, and the stakes appear to be especially high here. Some national observers say it now looks even more likely that the outcome of the Maine election could determine which party controls the majority in the Senate.

‘EVERY CHAMBER IS DIFFERENT’

Influencing control of Congress is not a traditional role for a chamber of commerce. The formation of chambers goes back more than a century as collectives of local merchants who worked together to serve and promote their communities.

Maine now has about 60 local and regional chambers, each of which is an independent organization.

“Every chamber is different. You’ve seen one; you’ve seen one,” said Chip Morrison, president of the Androscoggin County Chamber of Commerce.

Morrison’s group dates to 1888 and serves about 1,400 members with programs such as human resources and marketing training, business promotion, job fairs and business counseling. It has never endorsed a candidate. “We have to work with everybody,” he said.

Morrison has been getting a lot of flack about the U.S. Chamber’s ad, he said.

“I’ve gotten it from Republicans saying that I’m favoring Angus King because I’m saying we don’t endorse anybody, and I’ve heard it from (others) because we’re not repudiating the U.S. Chamber ads,” he said. “I guess the big issue is you work hard to establish a brand and everybody gets associated with the use of the word ‘chamber.’ “

The Androscoggin County group, like local groups statewide, is a member of the State Chamber of Commerce, which, in turn, is a member of the U.S. Chamber. The Androscoggin County group is not directly a member of the U.S. Chamber.

“They have some great programs, but because of the political thing we don’t join,” Morrison said.

Morrison said the national group also is seen as having a big-business bias, while Maine’s local and state chambers are more focused on the issues facing small businesses that make up the Maine economy.

The U.S. Chamber has historically been more politically active than state and local groups, and it has become much more aggressive under new leadership during the past decade.

“In recent years, they have tended to focus on federal spending, unnecessary government regulation and the health care reform law, or Obamacare, which they see as imposing additional costs on business,” said Anthony Corrado, a government professor at Colby College and nationally known expert on political finance. “The Chamber feels that they are better off with a Republican majority.”

POLITICAL EXPENDITURES RISE

The Chamber reported $215 million in income in 2010, the last year for which information is available. As a nonprofit organization, it is not required to list its income sources, so it is unclear where the money comes from.

“They have a whole bunch of very large corporate members,” said Bill Allison, editorial director for the Sunlight Foundation, a nonprofit government watchdog group. “We don’t know everybody who belongs, (and) they don’t have to do any sort of disclosure about how much these organizations are charged.”

The U.S. Chamber spent $41 million lobbying Congress in 2002, and that grew to $144 million in 2009 while fighting passage of the Affordable Care Act, Corrado said. It also has a political action committee that donates to candidates.

The U.S. Chamber has especially increased independent political expenditures such as buying TV ads in Maine and other states without coordinating directly with any candidates. Such independent spending is growing fast this year after recent Supreme Court decisions that allow nonprofit groups to spend on “voter education” ads without disclosing where the money comes from.

The U.S. Chamber is believed to have spent about $50 million to influence national elections in 2010, and has said it plans to spend $100 million this year, according to Corrado.

Engstrom would not comment on spending plans in Maine or nationwide. He said the chamber has endorsed Democrats that share its views, but tends to favor Republicans because they are more likely to favor the repeal of the Affordable Care Act and domestic drilling for oil, among other key issues important to its members.

The U.S. Chamber claims about 300,000 members, including large and small businesses and state and regional chambers. When all the members of those smaller groups are counted, the chambers says, it speaks for about 3 million businesses.

Engstrom dismissed complaints that the Chamber does not reveal its donors to the Federal Elections Commission. The group’s money comes from member businesses, which pay dues and contribute to political activity, he said. “People know who the U.S. Chamber of Commerce is.”

A spokeswoman for the group said it has hundreds of members in Maine, although the chamber would not provide a list of its Maine members.

Some small business owners in Maine that aren’t members of the U.S. Chamber spoke out against the group when Engstrom was here last week.

“The U.S. Chamber doesn’t care about small businesses in Maine,” Craig Saddlemire, a Lewiston small business owner and city councilor said in a news release from the Maine Small Business Coaliton. “They represent the extreme agenda of multinational corporations and the health insurance industry and the fact that they’re trying so hard to influence our elections here in Maine is deeply troubling.”

Jimmy Simones, owner of Simones Hot Dog Stand in Lewiston, is a member of the U.S. Chamber. He also hosted Summers and Engstrom for one of their campaign stops last week. But he said he is not endorsing Summers and would not comment on the anti-King ad.

“We get along with everybody,” said Simones, who has pictures on the wall showing politicians of every stripe in his restaurant. King was there the previous week, in fact. “We have left, we have right, we have center, we have every wing.”

Connors said the Maine State Chamber is confident that its dues don’t help pay for the U.S. Chamber’s political activity. Nevertheless, Connors said, he would rather not have the word “chamber” attached to negative political ads.

“It puts us into a political position that we just don’t want to be in.”

Staff Writer John Richardson can be contacted at 791-6324 or at:

jrichardson@pressherald.com

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story