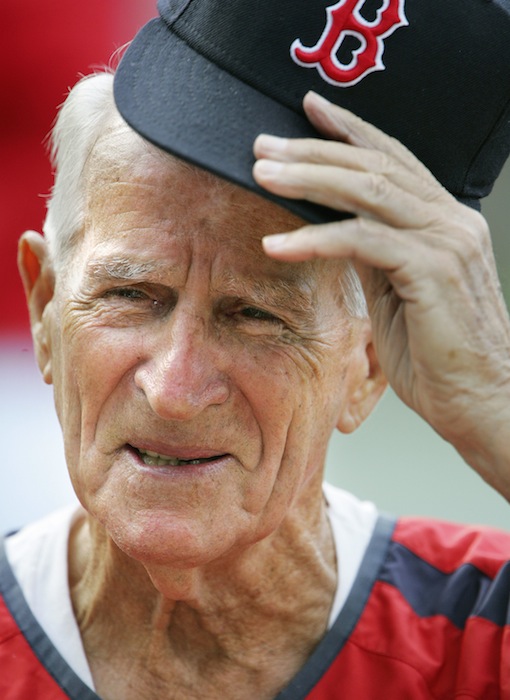

Adored by generations of Red Sox fans, Johnny Pesky was so much a part of Boston baseball that the right-field foul pole at Fenway Park was named for him.

Pesky, who played, managed and served as a broadcaster for the Red Sox in a baseball career that lasted more than 60 years, died Monday. He was 92.

“The national pastime has lost one of its greatest ambassadors,” baseball commissioner Bud Selig said. “Johnny Pesky, who led a great American life, was an embodiment of loyalty and goodwill for the Boston Red Sox and all of Major League Baseball.”

Pesky died just more than a week after his final visit to Fenway, on Aug. 5 when Boston beat the Minnesota Twins 6-4.

Yet for many in the legion of Red Sox fans, their last image of Pesky will be from the 100th anniversary of Fenway Park on April 20, when the man known for his warmth, kindness and outstanding baseball career was moved to tears at a pregame ceremony. By then the former shortstop was in a wheelchair positioned at second base, surrounded by dozens of admiring former players and a cheering crowd.

“I feel like part of the Red Sox tradition just died because when I think of Johnny I think of him hitting fungos at spring training. We will all miss him so much,” ex-pitcher Pedro Martinez said in comments provided by the Red Sox. “He was such a representative of everything that happened in Boston. It’s hard to think of the success, defeat, and all we went through without Johnny. You couldn’t do anything without Johnny Pesky.”

It was at another ceremony less than six years earlier that Pesky’s name was officially inscribed in the rich history of the Red Sox and their home, a fitting tribute to a career .307 hitter and longtime teammate and friend of Ted Williams.

On his 87th birthday, Sept. 27, 2006, a plaque was unveiled at the base of the foul pole just 302 feet from home plate, designating it “Pesky’s Pole.”

The term was coined by former Red Sox pitcher Mel Parnell, who during a broadcast in the 1950s recalled Pesky winning a game for him with a home run around the pole. From there, a legend seemed to grow that Pesky frequently curled shots that way — actually, only six of his 17 career home runs came at Fenway.

In fact, team records show that Pesky never hit a home run at Fenway in which Parnell was the winning pitcher. Still, Pesky’s spot in the hearts of Red Sox players and fans alike is indisputable.

“This is a very sad day for me and for anyone who has ever spent any time with Mr. Pesky. He was the most positive influence I ever came across who wore the Red Sox uniform,” said Jason Varitek, the team’s former captain.

“He was always there through the good and bad times with the same smile and passion for his team. ‘Hello my honeysuckle, hello my honey bee, my ever lovin’ Jason just got three,’ Johnny used to say, wishing me three hits that night.”

Even though Pesky was a fan favorite, he still had his own place of notoriety in Boston’s drought of 86 years without a championship. He was long blamed for holding the ball on a key relay in Game 7 of the 1946 World Series, though it’s a place that many now think is undeserved.

“Johnny Pesky will forever be linked to the Boston Red Sox,” team president Larry Lucchino said. “He has been as much a part of Fenway Park as his retired Number 6 that rests on the right-field facade, or the foul pole below it that bears his name.”

Pesky died at the Kaplan Family Hospice House in Danvers, according to Solimine, Landergan and Richardson funeral home in Lynn. The funeral home did not announce a cause of death.

“I’ve had an interesting life,” Pesky told The Associated Press in 2005. “I have no complaints.”

In New York, a moment of silence was held at Yankee Stadium before Monday night’s game against the Texas Rangers. The crowd gave a nice round of applause.

“There wasn’t a greater gentleman of the game,” said Hall of Famer Wade Boggs, a star third baseman with both the Red Sox and Yankees. “Johnny was loved by everyone. He would light up your day when he walked in the room.”

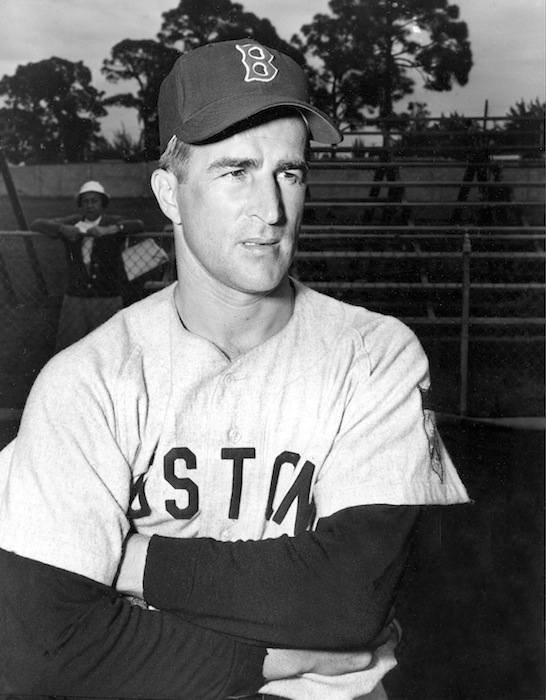

Longtime Red Sox fans recall the days when Pesky was a talented shortstop and manager for the team. Younger ones saw him as an avuncular presence at the Red Sox spring training camp in Fort Myers, Fla.

It was there that Pesky would encourage young players and hit grounders to infielders with his ever-present fungo bat. He stopped doing that as he aged but still spent time sitting in a folding chair, his bat by his side, signing autographs and chatting with fans of all ages.

“I’ve had a good life with the ballclub,” Pesky told the AP in 2004. “I just try to help out. I understand the game, I’ve been around the ballpark my whole life.”

Pesky was a special assignment instructor in 2004 when the Red Sox won their first championship in 86 years. Tears of joy glistened in his eyes when the World Series was over.

“One of my career memories was hugging and kissing Johnny pesky after we won it all in 04, God Rest and God Bless his gentle soul, I miss you,” Curt Schilling, who starred on that team, tweeted.

Current Red Sox players also took to Twitter.

David Ortiz: “A very dark day today for red sox nation.”

Jon Lester: “Just heard we lost one of the good ones today. A great player and an even better man, rest in peace Johnny, thank you for the memories.”

Pesky played 10 years in the majors, the first seven-plus with Boston. His No. 6 was retired by the Red Sox at a ceremony in 2008. Pesky stood under an umbrella at home plate that day, wearing the team’s white home uniform.

“All of Red Sox Nation mourns the loss of ‘Mr. Red Sox,’ Johnny Pesky,” Boston mayor Thomas Menino said. “He loved the game and he loved the fans — and we loved him. His dedication to the sport and his passion to improve the game through the mentorship of young players will be sorely missed. Our hearts go out to the Red Sox organization and all of Johnny’s family and many friends.”

Former Red Sox first baseman and outfielder Kevin Millar was one of them.

“Johnny is the greatest man I have ever met in this wonderful game,” he said.

Born John Michael Paveskovich in Portland, Ore., Pesky first signed with the Red Sox organization in 1939 at the urging of his mother. A Red Sox scout had wooed her with flowers and his father with fine bourbon. His parents, immigrants from what is now Croatia, didn’t understand baseball, but they did understand that the Red Sox were the best fit for their son even though other teams offered more money.

He played two years in the Red Sox minor league system before making his major league debut in 1942.

That season he set the team record for hits by a rookie with 205, a mark that stood until 1997 when fellow Red Sox shortstop Nomar Garciaparra, with whom he became very close, had 209. He also hit .331 his rookie year, second in the American League only to Williams, who hit .356.

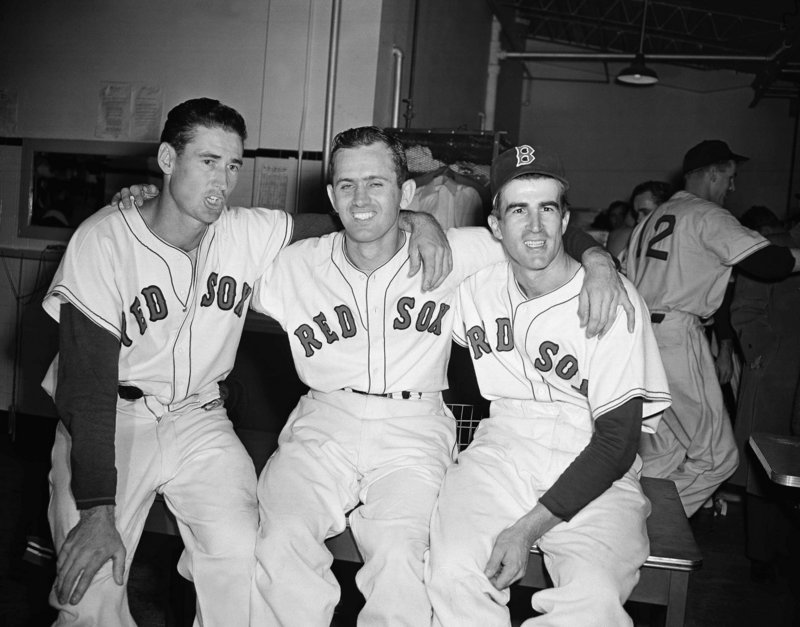

Pesky spent the next three years in the Navy during World War II, although he did not see combat. He was back with the Red Sox through 1952, playing with the likes of Williams, who died in 2002, Bobby Doerr and Dom DiMaggio, before being traded to the Detroit Tigers. (In 2003, author David Halberstam told the story of Pesky, Williams, Doerr and DiMaggio in his book “The Teammates: A Portrait of a Friendship.”)

Doerr, a Hall of Fame second baseman and Pesky’s longtime double-play partner, said the two were friends since 1934, when Doerr broke into the Pacific Coast League with the Hollywood Stars and Pesky was the clubhouse boy in Portland.

“He would hang your jockstrap up. He would hang your wet sweat shirt up. That’s kind of how close we were,” the 94-year-old Doerr told the AP from his home in Junction City, Ore. “We got to be good friends. When he got to the Red Sox, we roomed together.

“He was good to play alongside of. He hit a lot of line drives. He could run. He beat out a lot of balls to first base,” Doerr recalled. “When he got a good pitch to hit, he hit it.”

Pesky was often said to have held the ball for a split second as Enos Slaughter made his famous “Mad Dash” from first base to score the winning run for the St. Louis Cardinals against the Red Sox in the deciding game of the 1946 World Series.

With the score tied at 3, Slaughter opened the bottom of the eighth inning with a single. With two outs, Harry Walker hit the ball to center field. Pesky, playing shortstop, took the cutoff throw from outfielder Leon Culberson, and according to some newspaper accounts, hesitated before throwing home. Slaughter, who ran through the stop sign at third base, was safe at the plate, and the best-of-seven series went to the Cardinals.

“I thought he got rid of it pretty good. There was no fault of Johnny’s on that,” Doerr said.

Pesky always denied any indecision, and analysis of the film appeared to back him up, but the myth persisted.

“In my heart, I know I didn’t hold the ball,” Pesky once said.

Pesky spent two years with the Tigers and Senators before starting a coaching career that included a two-year stint as Red Sox manager in 1963 and 1964. He came back to the Red Sox in 1969 and stayed there, even filling in as interim manager in 1980 after the club fired Don Zimmer.

“Johnny bleeds Red Sox red. He couldn’t do enough to help you out,” former Boston outfielder Fred Lynn said. “John was our hitting coach and he was almost like a dad to me. When I’d line out he’d say, ‘Hey, you see that guy standing there? Don’t hit it there. You’re a college guy.’ Being with Johnny was like being with my dad all day. I always joked that Johnny hit 200 singles in a year, and I hit 200 in my career.”

Pesky is survived by a son, David. His wife, Ruth, whom he married in 1944, died in 2005.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story