WASHINGTON — Charles Colson, the tough-as-nails special counsel to President Richard Nixon who went to prison for his role in a Watergate-related case and became a Christian evangelical helping inmates, has died. He was 80.

Colson’s death was confirmed by Jim Liske, the chief executive of the Lansdowne, Va.-based Prison Fellowship Ministries that Colson founded. Liske said the preliminary cause of death is complications from brain surgery Colson had at the end of March.

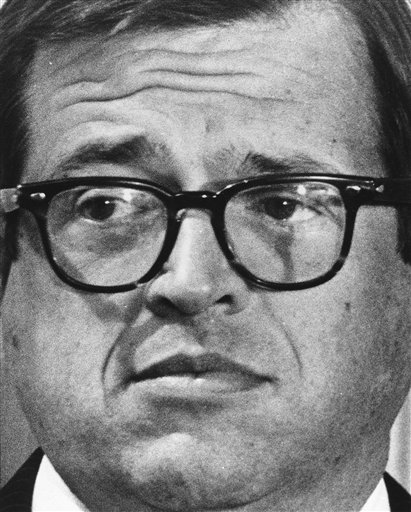

Colson, with his trademark horn-rimmed glasses, was known as the “evil genius” of the Nixon administration who once said he’d walk over his grandmother to get the president elected to a second term.

“I shudder to think of what I’d been if I had not gone to prison,” Colson said in 1993. “Lying on the rotten floor of a cell, you know it’s not prosperity or pleasure that’s important, but the maturing of the soul.”

The Washington Post described him in 1972 as “one of the most powerful presidential aides, variously described as a troubleshooter and as a ‘master of dirty tricks.'”

He helped run the Committee to Re-elect the President when it set up an effort to gather intelligence on the Democratic Party. The arrest of CREEP’s security director, James W. McCord, and four other men burglarizing the Democratic National Committee offices in 1972 set off the scandal that led to Nixon’s resignation in August 1974.

But it was actions that preceded the actual Watergate break-in that resulted in Colson’s criminal conviction. Colson pleaded guilty to efforts to discredit Pentagon analyst Daniel Ellsberg. It was Ellsberg who had leaked the secret Defense Department study of Vietnam that became known as the Pentagon Papers.

The efforts to discredit Ellsberg included use of Nixon’s plumbers — a covert group established to investigate White House leaks — in 1971 to break into the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist to look for information that could discredit Ellsberg’s anti-war efforts.

The Ellsberg burglary was revealed during the course of the Watergate investigation and became an element in the ongoing scandal. Colson pleaded guilty in 1974 to obstruction of justice in connection with attempts to discredit Ellsberg, though charges were dropped that Colson actually played a role in the burglary of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office. Charges related to the actual Watergate burglary and cover-up were also dropped. He served seven months in prison.

Before Colson went to prison he became a born-again Christian, but critics said his post-scandal redemption was a ploy to get his sentence reduced. The Boston Globe wrote in 1973, “If Mr. Colson can repent of his sins, there just has to be hope for everyone.”

Ellsberg, for his part, said in an interview that Colson never apologized to him and did not respond to several efforts Ellsberg made over the years to get in touch with him. Ellsberg said he still believes that Colson’s guilty plea was not a matter of contrition so much as an effort to head off even more serious allegations that Colson had sought to hire thugs to administer a beating against Ellsberg — an allegation that Colson states in his book was believed by prosecutors despite his denial.

“I have no reason to doubt his evangelism,” Ellsberg said of Colson. “But I don’t think he felt any kind of regret” for what he had done, except remorse that he had been ineffective and got caught.

Colson stayed with his faith and went on to win praise — including the prestigious Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion — for his efforts to use it to help others. Colson later called going to prison a “great blessing.”

He created the Prison Fellowship Ministries in 1976 to minister to prisoners, ex-prisoners and their families. It runs work-release programs, marriage seminars and classes to help prisoners after they get out. An international offshoot established chapters around the world.

“You can’t leave a person in a steel cage and expect something good to come out of him when he is released,” Colson said in 2001.

His approach led to court challenges to the use of state facilities to foster one religion, Christianity, in violation of the constitutional separation of church and state.

While faith was a large part of his message, Colson also tackled such topics as prison overpopulation and criticized the death penalty, though he thought it could be justified in rare cases. He said those convicted of nonviolent crimes should be put on community-service projects instead of being locked up.

He wrote more than 20 books, including “Born Again: What Really Happened to the White House Hatchet Man,” which was turned into a movie. Royalties from all his books have gone to his ministry program, as did the $1 million Templeton prize, which he won in 1993.

Colson also wrote a syndicated column, and started his daily radio feature, BreakPoint, which airs on more than 1,000 radio networks, according to the PFM Web site.

The Boston native earned his bachelor’s degree from Brown University in 1953 and served as a captain in the Marine Corps from 1953 to 1955. In 1959, he received his doctorate with honors from George Washington University.

He spent several years as an administrative assistant to Massachusetts Sen. Leverett Saltonstall. Several years later, Nixon made him his special counsel in November 1969.

In the mid-1990s Colson teamed up with the Rev. Richard Neuhaus to write “Evangelicals and Catholics Together: The Christian Mission in the Third Millennium,” calling for Catholics and evangelicals to unite and accept each other as Christians.

In February 2005, Colson was named one of Time magazine’s “25 Most Influential Evangelicals in America.”

Time commended Colson for helping to define compassionate conservatism through his campaign for humane prison conditions and called him one of “evangelicalism’s more thoughtful public voices.”

“After decades of relative abstention, Colson is back in power politics,” Time wrote.

Mark Earley, a former Virginia attorney general who became president and chief executive officer of PFM after his failed gubernatorial run in 2001, said the influence of Colson’s work in his ministry is a different kind of power from what he had as Nixon’s special counsel.

“Yet, it wasn’t until he lost that power, what most people would call real ‘power,’ that Chuck began to make a real difference and exercise the only kind of influence that really matters,” Earley said on BreakPoint.

“Prison Fellowship is possible only because its founder, Chuck Colson, was forced to personally identify with those people who hold a special place in God’s heart: prisoners and their families.”

In October 2000, Florida Gov. Jeb Bush restored Colson’s civil rights, allowing him to vote, sit on a jury, run for office and practice law. Colson had a home in Naples, Fla., and Bush called him “a great guy … a great Floridian.”

Five years later, when it was revealed that Mark Felt was the infamous “Deep Throat” responsible for the fall of the Nixon administration, Colson was disgusted, having worked so closely with Felt. “He goes out of his life on a very sour note, not as a hero,” Colson said.

Still, Colson credited the Watergate scandal with enriching his life.

God “used that experience — Watergate — to raise up a ministry that is reaching hundreds of thousands of people,” Colson said in the late 1990s. “So I’m probably one of the few guys around that’s saying, ‘I’m glad for Watergate.'”

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story