WASHINGTON — The individual insurance requirement that the Supreme Court is reviewing isn’t the first federal mandate involving health care.

There’s a Medicare payroll tax on workers and employers, for example, and a requirement that hospitals provide free emergency services to indigents. Health care is full of government dictates, some arguably more intrusive than President Barack Obama’s overhaul law.

It’s a wrinkle that has caught the attention of the justices.

Most of the mandates apply to providers such as hospitals and insurers. For example, a 1990s law requires health plans to cover at least a 48-hour hospital stay for new mothers and their babies. Such requirements protect some consumers while indirectly raising costs for others.

One mandate affects just about everybody: Workers must pay a tax to finance Medicare, which collects about $200 billion a year.

It’s right on your W-2 form, line 6, “Medicare tax withheld.” Workers must pay it even if they don’t have health insurance. Employees of a company get to split the tax with their employer. The self-employed owe the full amount, 2.9 percent of earnings.

Lindsey Donner, a small-business owner from San Diego, pays the Medicare tax although she and her husband are uninsured. Donner, 27, says she doesn’t see much difference between the mandate that workers help finance Medicare and the health care law’s requirement that nearly everyone has to have some sort of health insurance.

“My understanding of what is going on in the Supreme Court is that it seems to be something of a semantics issue,” she said. “Ultimately, I don’t see the big difference. If I am paying for Medicare, why can’t I also be paying into something that would help me right now or in five years if I want to have children?”

Donner is a copy writer for businesses; her husband specializes in graphics design. In the past they had a health plan with a high deductible, but they found they were paying monthly premiums for insurance they never used — something she said they couldn’t afford on a tight budget.

Under the law, people such as Donner and her husband would have to get insurance or pay a fine. But they may qualify for federal subsidies to help pay premiums for policies that would be more comprehensive. Preventive care would be covered with no co-payments.

“We have jobs, we pay our bills, we pay our taxes,” said Donner. “Yet it is very difficult to find affordable, reasonable health care.”

There’s no question the Medicare payroll tax is a government mandate, said Mark Hayes, former chief health counsel for the Republican staff of the Senate Finance Committee.

But he makes a distinction between the payroll tax and the individual health insurance mandate in Obama’s health care law.

Congress used more clearly defined constitutional powers when it created Medicare. “The power to tax and the power to spend,” Hayes said. “Here, with the individual mandate, it’s a different question — regulating interstate commerce. This is a novel question from a legal standpoint.”

Obama’s law makes health insurance both a right and a responsibility for most. It would provide coverage to more than 90 percent of the population, subsidizing private insurance for millions. But it also requires nearly everyone to carry health insurance, either through an employer or a government program, or by buying an individual policy.

The mandate is well within the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce, the administration and the law’s supporters contend. Opponents say Congress overstepped constitutional bounds by effectively requiring individuals to purchase a particular product.

Supreme Court justices are trying to determine the distinction between Obama’s law and other mandates, and whether it makes a difference.

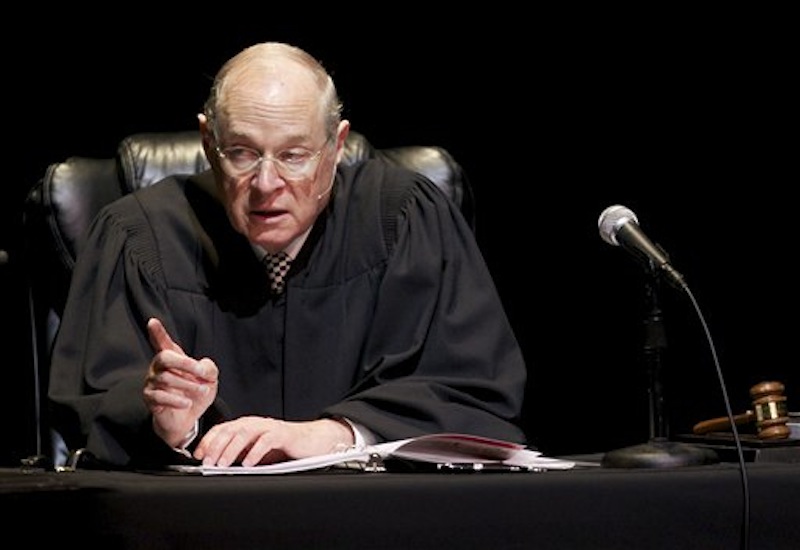

Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Anthony Kennedy raised the matter during oral arguments last week.

Ginsburg brought up Social Security as an example, likening it to a government old-age annuity that everyone is forced to purchase.

“It just seems very strange to me that there’s no question we can have a Social Security system (despite) all the people who say: ‘I’m being forced to pay for something I don’t want,'” she said.

“There’s something very odd about that, that the government can take over the whole thing and we all say, ‘Oh, yes that’s fine,’ but if the government wants to … preserve private insurers, it can’t do that.”

Kennedy mused that Congress could have created a Medicare-style program for the uninsured, run exclusively by the government without the involvement of private insurers.

“Let’s assume that (Congress) could use the tax power to raise revenue and to just have a national health service, single payer,” said Kennedy. “How does that factor into our analysis? In one sense, it can be argued that this is what the government is doing; it ought to be honest about the power that it’s using and use the correct power.

“On the other hand, it means that since … Congress can do it anyway, we give a certain amount of latitude,” Kennedy continued. “I’m not sure which way the argument goes.”

The case may well turn on how Kennedy decides.

Social Security and Medicare are no longer controversial mandates because they are part of the social fabric, said Hayes, the former GOP congressional aide. Not so the health care law’s mandate. “Today, this is controversial because it is novel from a legal standpoint and also new from a societal standpoint,” he said.

The distinction frustrates supporters of the health care law.

“It’s so crazy to think that a society that has Social Security and Medicare would not find this (law) constitutional,” said MIT economist Jonathan Gruber, who advised both the Obama administration and Massachusetts lawmakers as they developed the state mandate in the 2006 law that Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney championed as governor.

“The payroll tax is worse than the mandate, because that is a program where we take your money and there is no ability to get out of it,” Gruber said. Citizens can avoid the health insurance mandate by paying a penalty to the Internal Revenue Service.

Other federal health care mandates include:

— The 1986 Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act. It requires nearly all hospitals to treat and stabilize anyone needing emergency care, regardless of ability to pay or legal U.S. residency. Critics call it an unfunded mandate. It was part of a budget law signed by President Ronald Reagan.

— The 1996 Mental Health Parity Act. It prohibits group health plans from setting lower annual or lifetime dollar limits for mental health benefits as compared with medical and surgical benefits.

— The 1996 Newborns’ and Mothers’ Health Protection Act. It requires plans offering maternity coverage to pay for at a least a 48-hour hospital stay following most normal deliveries, and 96 hours following a Caesarean section. The mental health parity and maternal health laws were signed by President Bill Clinton.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Comments are no longer available on this story